The dockyard at Chatham, in the county of Kent in southeastern England, was one of the Royal dockyards which possessed the expensive dry docks and shore-side facilities lacking in most private shipyards. These facilities were critical to building, repairing, and maintaining the Royal Navy's fleet. As the largest industrial organisations in the world by the mid-18th century, such dockyards covered vast areas and employed thousands of workers across a large number of trades.

The River Medway had become the Royal Navy's principal fleet base during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603) and by 1570 the majority of repair and maintenance work on the fleet was being carried out at the Chatham Dockyard's original site. In 1588, Chatham's workers prepared the fleet to meet the threat posed by the Spanish Armada and, in 1613, the dockyard moved to its present site. The construction of storehouses and a ropewalk (rope-making facility) were constructed by 1618 and by 1625 a dry dock and houses for senior officials had been completed.

With the Royal Navy battling the Dutch fleet in the English Channel and North Sea from the mid-1600s, Chatham Dockyard was ideally placed to support the English ships at their nearby operational bases and soon became the pre-eminent shipbuilding and repair facility. The first of the dockyard's buildings to survive to the present day date from the early 1700s, when the Commissioner's House was built (1703-04); however, the location of naval operations in the 18th century had shifted westwards to the Mediterranean and North America, putting Chatham at a geographical disadvantage compared to the other major bases at Portsmouth and Plymouth. As such, Chatham shifted from being a fleet base to Britain's principal naval shipbuilding and repair yard.

Britain's most famous warship, HMS Victory, was constructed at Chatham. On 23 July 1759, her keel was laid in the Old Single Dock. After a lengthy delay, construction was restarted and Victory was launched on 7 May 1765. Following fitting out, Victory finally departed Chatham in 1778, participating in the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797. After a refit at Chatham, Victory was recommissioned as Admiral Horatio Nelson's flagship and engaged in the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805.

The heavy demands on the dockyard's facilities led to major expansion and improvements, as well as the industrialisation of many of the yard's processes. New storehouses, a lead and paint mill, the Royal Dockyard Church, officers' offices, a steam-powered sawmill, and the No. 1 Smithery were erected in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The 1,135 foot long Double Ropehouse was completed in 1791. In 1820, Chatham's first stone dry dock and the engine house for a steam-powered dock pump were built.

The 1830s ushered in the Age of Steam at Chatham Dockyard, with the yard's first steam-powered vessel, the sloop Phoenix, launched in September 1832. In 1849, the construction of all remaining sailing ships was halted and in 1850 Chatham's first ship powered by a screw propeller, Horatio, was launched. Between 1838 and 1855, new covered building slips were erected in the dockyard, and the two remaining timber dry docks were rebuilt in granite.

On 13 August 1908, the Chatham Dockyard launched its first submarine, C17, a small coastal boat. Five more boats of the same class soon followed and the construction of submarines soon became a specialty of the Chatham Dockyard up until the mid-1960s. A total of 57 submarines would eventually be built at Chatham between 1908 and 1960, including the X- and M-class boats of the interwar period, the T-class boats of the Second World War period, and six of the Oberon-class of the post-war period. The last warship to be constructed at Chatham for the Royal Navy was the Oberon-class sub HMS Ocelot, launched in 1962. Three Oberon-class boats were also built here for the Royal Canadian Navy; the last, HMCS Okanagan, was launched on 17 September 1966.

While no warships were constructed at Chatham after 1966, the dockyard continued to serve as a ship and submarine repair facility, including for technologically complex nuclear submarine refits, until its closure in March 1984. Today, the most historic 80 acres of a facility that once covered 505 acres, including over 100 buildings and structures spanning the period from the 18th to the 20th centuries, have been preserved as the world's most complete example of a dockyard of the Age of Sail. Chatham Historic Dockyard is managed by the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust.

Chatham Historic Dockyard is home to three preserved Royal Navy vessels, now open to visitors: the sloop HMS Gannet, the C-class destroyer HMS Cavalier, and the Oberon-class submarine HMS Ocelot. Click on the links to see photos and information on each.

Photos taken 21 September 2015

|

| The main gate into Chatham Dockyard. The gatehouse was designed by the yard's Master Shipwright and erected in 1722. The coat of arms of George III have hung above the entrance since 1811 and was restored in 1994. |

The site map for the 80-acre Chatham Historic Dockyard:

|

| In 2015, the Road to Trafalgar exhibition within the Wooden Walls of England gallery, told the story of Chatham Dockyard's role in the Napoleonic Wars. It was at Chatham Dockyard that the 104-gun first rate ship of the line HMS Victory was built between 1759 and 1765. Victory became famous as the flagship of Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. |

|

| The No. 1 Smithery, built between 1806 and 1808. Grade I listed and designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument, the No. 1 Smithery was constructed to address the increasing use of iron in shipbuilding and the demands of the Napoleonic Wars. An expansion in 1861-69 accommodated new technologies and the new, steam-powered warships then being built at Chatham. Having been restored in 2010 under a partnership between the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, the National Maritime Museum, and the Imperial War Museum, the building now houses galleries and exhibitions (both permanent and temporary), as well as temperature controlled storage for many of the National Maritime Museum's collection of 4,000 ship models. |

|

| Some of the forges and ironworking equipment in the No. 1 Smithery. The forges were installed in Smithery in the 1850s and used to make small metal fittings and chain. Working in the Smithery was hot, noisy, and involved lifting heavy items. Because of this, the workers were permitted eight pints (4.5 litres) of strong beer per day, provided from a beer cellar in the Smithery's courtyard. |

|

| The large number of surviving historic buildings help recreate the feel of a dockyard of the Age of Sail. |

|

| On the left, 3 Slip (built 1838), one of the covered slipways, was once Europe's largest wide span timber structure. Today, it houses large artefacts from the dockyard and items from the nearby Royal Engineers Museum. The covered slips on the right today house the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) collection of 17 historic lifeboats. |

|

| A look inside 3 Slip, showing the enormous internal space covered by the timber roof. |

|

| The covered 3 Slip was built on the site of one of a pair of dry docks constructed in 1686. Designed by shipwright Sir Robert Seppings, 3 Slip's high cantilevered roof allowed ships to be constructed while protected from the elements. This was especially important as wooden sailing ships took years to construct, due to the requirement to allow their structural frames to season before planking could be installed on the hulls. The upward curve at the landward end of the building was designed to accommodate a ship's bow. |

|

| The Dock Pumping Station housed the pumps that drained Chatham Dockyard's first stone dry dock. Chatham Dockyard's first dry docks were shallow, timber-lined trenches drained by hand pumps. In the 19th century, the dry docks were reconstructed using granite blocks and drained by steam pumps in the Dock Pumping Station. |

|

| Chatham's Dock Pumping Station was the first such steam-powered dock pumping station built in Britain features a central boiler house with enclosed chimney, flanked by engine houses on each side. |

|

| A remote-control model of a Soviet Victor-class submarine built by Turks Boat Yard, based in Chatham Dockyard's No. 7 Slip. The model was used in the 1999 James Bond film, The World is Not Enough, starring Pierce Brosnan. Between 1967 and 1992, the Soviet Navy commissioned 48 Victor-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. The Victor-class boats, measuring between 92 and 102 metres (303 and 335 feet) in length, were armed with torpedoes and cruise missiles. |

|

| Two Second World War era Quick Firing (QF) 3.7-inch heavy anti-aircraft guns on mobile carriages, manufactured by General Electric. |

|

| One of the giant shipyard cranes in the Chatham Historic Dockyard. |

|

| Built in 1723, the Clock Tower Building is the oldest surviving naval storehouse in any of the Royal Dockyards. Used to store materials and equipment required by ships under construction or repair, the top floor of the Clock Tower Building was used as a mould loft, while the six ground floor bays were open and used as saw pits. While the Clock Tower Building was originally clad in timber, it was rebuilt in brick in 1802. The mould loft was used until 1758, when a larger one was built over the Mast Houses, and the saw pits were abandoned when the Brunel Sawmills opened in 1819. Today, the building houses Bridgewarden's College of the University of Kent. |

|

| A view over part of Chatham Historic Dockyard from the deck of HMS Gannet, one of the historic Royal Navy ships preserved in the dockyard. The submarine HMS Ocelot and the destroyer HMS Cavalier can be seen in the adjacent dry docks. |

|

| A view from HMS Cavalier's bridge. HMS Ocelot sits in No. 3 Dock, the first stone dry dock built at Chatham Dockyard. HMS Gannet resides in No. 4 Dock just beyond, with the grey-roofed No. 3 Slip in the background. The dockyard's four dry docks (three of which remain today) were the heart of the facility; while used for shipbuilding, their primary use was for ship repair and maintenance purposes. |

|

| A view down the main road runing through Chatham Historic Dockyard, past the Admiral's Offices and the Clock Tower Building on the right and the dry docks and other dockyard infrastructure on the left. |

|

| The Admiral's Offices, built in 1808 and used as offices for the dockyard's master shipwright. The low roofline was designed to avoid obstructing the view from the officers' terrace. The building later became the Port Admiral's offices and was extended in the 20th century, with the northern extension housing the dockyard's communications centre. |

|

| A close-up view of the entrance to the Admiral's Offices. |

|

| The Commissioner's House, built in 1704 and the oldest naval building in Britain to survive intact. This grand family home was constructed for the Commissioner of the dockyard. Today, the Commissioner's House is available for hire as a venue for weddings and other events, and includes a bridal suite, a ceremony room, a ballroom, a pavilion marquee, a bar, a patio courtyard, and Edwardian gardens. |

|

| The Ropery was where naval rope was manufactured for the ships being built and repaired at Chatham Dockyard; a typical sailing warship needed approximately 32 kilometres (20 miles) of rope just for its rigging. Rope has been made on this site since 1618, though the current Double Ropehouse building dates from 1791. Visitors require advance, timed tickets to participate in a 40-minute guided tour of the Ropery, where ropemakers demonstrate the art of spinning rope using Victorian-era techniques and equipment. |

|

| The entrance to the Ropery Laying Floor, located in a Hemp House dating from 1785. Chatham's Hemp Houses were built between 1729 and 1814 and were used to store the raw hemp imported from southern Russia and used to make finished rope. The Hemp Houses still feature many of their original fittings. Mechanical spinning machines were installed in 1864, with female workers hired to maintain the new equipment. The women were forbidden from interacting with the male workers, and were provided with separate entrances and canteens to keep them apart. |

|

| The interior of the Ropery, measuring one-quarter mile in length. Of the four original ropeyards at the Royal Dockyards in Chatham, Portsmouth, Plymouth, and Woolwich, Chatham's is the only one still producing rope. |

|

| A rope spinning machine combines the strands of fibre into rope, moving forward on its tracks as the tightly-wound rope shrinks. |

|

| A view of the old-fashioned tools and equipment used in the Ropery. Bicycles are used by staff to go from one end of the 1,135-foot long facility to the other. |

|

| Another view of the interior of the Ropery. Although rope manufactured here was originally made by hand, from 1811 onward the process was mechanised and powered by steam from 1826. The Master Ropemakers, a subsidiary charity of the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, continues to manufacture rope and rope-based gifts in this building for sale in the dockyard. |

|

| The Anchor Wharf Storehouses, built between 1778 and 1805 at the southern end of the dockyard. These were the largest storehouses built for the Royal Navy in Britain, with Storehouse 2 measuring 700 feet (210 metres) long. Storehouse 3 was used to store equipment from warships in reserve or undergoing repair; Storehouse 2 was used as a general storehouse. A gallery entitled Steam, Steel and Submarines in part of one of the Anchor Wharf Storehouses tells the story of the Chatham Dockyard between 1832 and 1984. |

|

| The figurehead from the battleship HMS Rodney (1884). Launched by the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh on 8 October 1884, HMS Rodney was the last Royal Navy battleship to carry a figurehead. |

|

| The inside of the Steam, Steel and Submarines gallery. |

|

| A diorama of the Chatham Dockyard in its heyday, with ships under construction in the dry docks. Of the 505-acre dockyard site, the most historic 80 acres have been preserved as the Chatham Historic Dockyard. |

|

| A model of HMS Achilles, built at the Chatham Dockyard in 1863. Achilles was the first iron-hulled ship to be built by the Chatham Dockyard and the largest ship in the world at her launch. |

|

| Liferings from HMS Cressy and HMS Aboukir. Along with sistership HMS Hogue, these Chatham-based armoured cruisers were sunk by the German submarine U-9 in the North Sea on 22 September 1914, leaving 1,459 British sailors dead. |

|

| A commemorative launching silk for HMS Calliope. A tradition within the Royal Navy, commemorative silks were printed and distributed to guests invited to the launching ceremonies. |

|

| A model of the County-class heavy cruiser HMS Cumberland, which underwent a refit at Chatham Dockyard in 1936. The refit included the addition of a fixed catapult and hangar for two Walrus scouting aircraft. In the years leading up to the Second World War, Chatham Dockyard was kept busy fitting anti-aircraft weapons and armour to Royal Navy warships. |

|

| A model of the Oberon-class diesel-electric submarine HMS Ocelot, preserved as a museum vessel at Chatham Historic Dockyard. Ocelot was the last warship constructed for the Royal Navy at Chatham and was launched on 5 May 1962. She served in the Royal Navy until August 1991. |

|

| A model of the Leander-class frigate HMS Hermione, the last warship to be refitted at Chatham. Hermione's departure from Chatham Dockyard on 21 June 1983 drew huge crowds. |

|

| A diorama of the nuclear submarine refitting and refuelling complex at Chatham Dockyard, which opened in 1968. The complex was constructed between No. 6 and No. 7 dry docks but closed, along with the rest of Chatham Dockyard, on 31 March 1984. |

|

| A board with the names and crests of the Royal Navy nuclear attack submarines that completed reactor refuellings at Chatham Dockyard between 1972 and 1983. |

|

| Models of HMNZS Achilles and Exeter, as well as one of the Admiral Graf Spee, complement a display on the Battle of the River Plate. |

|

| A model of HMNZS Achilles, a Leander-class light cruiser of the Royal New Zealand Navy. In 1939, Achilles was part of the Royal Navy's South Atlantic Cruiser Squadron led by squadron flagship HMS Ajax. Achilles, in company with Ajax and the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, was responsible for damaging the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee in the Battle of the River Plate on 13 December 1939. Forced into the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay, the captain of the Admiral Graf Spee soon decided to scuttle his badly-damaged ship rather than risk it falling into British hands. HMNZS Achilles was returned to the Royal Navy in September 1946 and subsequently sold to the Indian Navy in July 1948, being renamed INS Delhi. Delhi served in the Indian Navy until being decommissioned on 30 June 1978 and scrapped shortly thereafter. One of the ship's 6-inch gun turrets was presented by the Indian Navy to the Royal New Zealand Navy and installed at the entrance to Devonport Naval Base in Auckland. |

|

| A model of the York-class heavy cruiser HMS Exeter. Although badly damaged by the Admiral Graf Spee in the Battle of the River Plate, HMS Exeter returned to Britain, was repaired, and dispatched to the Far East. On 1 March 1942, Exeter was sunk by Japanese warships in the Second Battle of the Java Sea. |

|

| A model of the 14,890-ton German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, scuttled in Montevideo harbour in Uruguay following the Battle of the River Plate, 13 December 1939. |

|

| A model of HMS Chatham, a Type 22 frigate launched on 20 January 1988 and commissioned on 4 May 1990. Although built on the River Tyne in northern England, HMS Chatham was named in honour of the city of Chatham's strong naval connections. Budget cuts led to the decommissioning of HMS Chatham on 9 February 2011, and in 2013 the ship was towed to a scrapyard in Turkey for dismantling. |

|

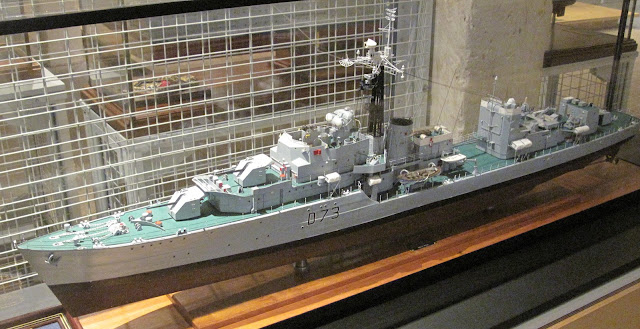

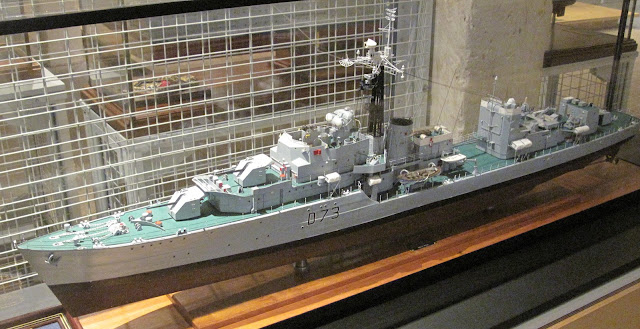

| A model of the C-class destroyer HMS Cavalier, one of the museum ships at Chatham Historic Dockyard. |

|

| A view of some of the artefacts, models, and displays displayed in the Steam, Steel and Submarines gallery. |

|

| The brass bell from the King George V-class battleship HMS Anson. Anson was launched on 24 February 1940 and commissioned into the Royal Navy on 14 April 1942. After a short but active service life, HMS Anson was decommissioned in November 1951 and scrapped on 17 December 1957. |

|

| A Mark 17 contact sea mine used by the Royal Navy. These mines were deployed at precise depths under water, floating at the end of a cable tethered to a sinker on the seabed. They were triggered by a vessel striking the contact horns jutting out from the body of the mine. |