Photos taken on 3 November 2019 except as noted

|

| The main entrance to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic on Lower Water Street, Halifax. The museum comprises the restored 1880s Robertson Ship Chandlery building (left) and the modern Devonian Wing (right), opened in 1981. |

|

| The reception and admissions desks. |

Below: the floor plan of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

|

| A double-ended lifeboat from a ship named Madeleine, on display in the lobby of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. |

|

| Entering the first gallery of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, dedicated to the role of the navy. The Royal Navy and, later, the Royal Canadian Navy have been a fixture of Halifax, being the home port of the Royal Navy's North Americas and West Indies Station and the Royal Canadian Navy's Atlantic Fleet. |

|

| The first-order dioptric Fresnel lens used in the Sambro Island lighthouse between 1906 and 1967. The Sambro Island lighthouse,located southwest of the entrance to Halifax Harbour and 2.5 km (1.6 mi) from the nearest land, was built in 1758 and is the oldest lighthouse in the Americas. Its construction was the first act of the first elected legislature of Nova Scotia, with the cost being covered by a special tax on liquor imports. Seven metres (22 feet) were added to the top of the lighthouse in 1906 and this lens was installed, making the light visible from a distance of 17 nautical miles (31.5 km; 19.6 mi). Since 2008, the Sambro Island lighthouse has used a solar-powered light. |

|

| The Directional Code Beacon (DCB) 36 electric beacon used in the Sambro Island lighthouse between 1968 and 2008. The DCB 36, with its 1,000 watt bulb, replaced the lighthouse's earlier first-order Fresnel lens and kerosene burner, dating from 1906. These electric beacons were originally developed for airports in the 1930s but were installed in a number of major Atlantic Canadian lighthouses in the 1960s after electricity lines were laid to remote capes and islands in the region. The DCB 36 was reliable and required little maintenance, running non-stop for decades until replaced by the current solar light installed at Sambro Island in 2008. |

|

| A diverse collection of artefacts and displays in Navy Gallery. |

|

| A diorama of Halifax Naval Yard, established in 1758. Serving as the primary base of British naval forces in the Northwest Atlantic, the diorama depicts the dockyard as it would have appeared in early June 1813. The diorama features a number of scenes showing the busy activity of a bustling naval dockyard, such as the human-powered Sheer Legs used to remove and install the tall, wooden masts on warships of the Age of Sail (circa mid-16th to mid-19th centuries). |

|

| The nine-foot long diorama, modelled at a scale of 1:300 (1 millimetre = 1 foot), depicts the dockyard as it may have appeared in the days just prior to the arrival of the captured USS Chesapeake, under escort by the British frigate HMS Shannon during the War of 1812. Seen here, a small three-masted warship is moored to a swing mooring in the dockyard while, at the jetty in the background, another warship is careened to expose its bottom for cleaning or repair, a practice common where drydocks were not available. |

|

| Part of the display on war at sea in the Age of Sail. |

|

| The Dock Yard Bell installed at the main gate of Halifax Naval Yard upon its opening in 1759. The bell was used to mark the hours in the years before Halifax had a town clock, and was also used to summon workers or raise alarms in the case of emergencies. With the dock yard having been extensively renovated and reconstructed over the years, most notably during the Second World War, this bell is one of the facility's few items from the Age of Sail to have survived. |

|

| A model of HMCS Niobe, the Royal Canadian Navy's first flag ship. She was armed with 16 quick-firing 6-inch guns, 12 quick firing 12-pounder guns, five 3-pounder guns, and two 18-inch torpedo tubes. Built in 1898 for the Royal Navy, this 11,000-ton Diadem Class protected cruiser served in the Boer War and was transferred to the newly-formed Royal Canadian Navy in 1910, at which point the ship was already obsolete. The ship's large size proved a challenge for Canada's fledgling navy and she spent much of her Canadian career docked in port to save money and to permit repairs to be completed after running aground at Cape Sable in 1911. Upon the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Niobe patrolled the American coast for German ships until being converted to a depot ship at Halifax Naval Yard in 1915. Badly damaged by the Halifax Explosion of 1917, which killed 23 of Niobe's crew, the ship remained as a floating depot until being sold for scrap in 1920. |

|

| A display of naval ordnance. The gun on the pedestal mounting is a quick firing 3-pounder Hotchkiss gun mounted on the British cruiser HMS Antrim in 1903. The gun was given to the Royal Canadian Navy upon Antrim's scraping in 1921 and was later installed aboard a Royal Canadian Navy Fairmile motor launch operating out of Halifax during the Second World War. After seeing service on the Royal Canadian Mounted Police cutter Irvine, the gun was donated to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in 1966. The brass cannon is a 2-pounder saluting gun, a miniature version of the carriage guns used aboard sailing warships in the 19th century, and used to honour important events or people. The black gun in the cradle is a 24-pounder carronade, a type of short-barelled gun that fired a heavy shot over short distances. Taking up less space aboard ship than a traditional carriage gun, carronades allowed warships to carry more guns and offer a heavier weight of shot. This particular carronade is from an unknown British warship at Halifax during the War of 1812. |

|

A 1:64 scale model of HMS Challenger, a Royal Navy corvette built in 1858 and equipped with both sails and an early steam engine and propeller. The ship measured 61 metres (200 feet) in length, with a beam of 12 metres (40 feet), a draught of 4.6 metres (15 feet), and a displacement of 2,343 tons; her crew numbered 243 officers and men. The funnel could be lowered and the propeller raised out of the water when the ship was operating under sail power to conserve coal. In 1872, the ship was stripped of most of its 21 guns guns to make way for laboratories which were installed aboard to support an around-the-world voyage of scientific research which was instrumental to the establishment of the field of Oceanography. During this voyage, which lasted until 1876, Challenger conducted research off the coast of Nova Scotia and visited Halifax in 1873. Converted to a drill ship following the voyage, HMS Challenger was scrapped in 1921.

|

|

| The figurehead from the 72-gun Royal Navy ship HMS Imaum, built in Bombay, India in 1826. Originally named Liverpool and owned by the Imaum of Muscat, she was sailed to Britain in 1836 and presented to the Royal Navy, which renamed her Imaum. Serving in the West Indies, HMS Imaum was decommissioned in 1863 and scrapped in Jamaica. After Imaum's scrapping, this figurehead was displayed at the Royal Navy Dock Yard in Port Royal, Jamaica and transferred to Bermuda in 1921. Following the closure of the Bermuda Dock Yard in 1951, the Royal Canadian Navy was given permission to take the figurehead to Halifax. |

|

| A scale model of the fisheries protection cruiser Canadian Government Ship (CGS) Canada, built in 1904 in Barrow-in-Furness, UK by Vickers Sons & Maxim Ltd. The ship measured 63 metres (206 feet) in length, with a beam of 7.65 metres (25.1 feet), a draught of 4.66 metres (15.3 feet), and a displacement of 750 tons. CGS Canada was armed with two 12-pounder guns and two 3-pounder guns and carried a crew of 60. As Canada did not yet have a navy in 1904, CGS Canada was viewed as a first step towards a naval force and the ship was used to train the country's first naval cadets. In the First World War, CGS Canada was commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy as HMCS Canada and used as a patrol vessel. Sold to civilian buyers after the war, the ship sank off the coast of Florida in 1926. |

|

| A wooden officer's chest from the USS Chesapeake, the American ship captured by the Royal Navy frigate HMS Shannon on 1 June 1813 and brought to Halifax as a prize. |

|

| The bell of HMS Shannon, showing the scars and cracks from the battle with the American frigate USS Chesapeake on 1 June 1813. Although a shot from Chesapeake shattered the top of the bell and punched a hole in its side, workers at the Royal Navy Dock Yard in Bermuda reassembled the pieces and the bell was later presented to Shannon Park School in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. When the Shannon Park naval base closed in 2004, the bell was transferred to the Maritime Command Museum in Halifax and loaned to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic for display. |

|

| A 1:64 scale model of the Royal Navy frigate HMS Sirius. The 36-gun Sirius was built in 1797 and was a good example of the kind of frigates the formed the backbone of the Royal Navy's squadrons during the Napoleonic Wars, including those based at Halifax. Such frigates were used for patrolling, blockading, convoy escort, and special operations. HMS Sirius participated in the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805 and served in the Atlantic, West Indies, and Indian Ocean during her career. She was destroyed by fire during an unsuccessful attack on Mauritius in 1810. |

|

| The Second World War display in the Navy Gallery. Glass display cases hold scale models of famous Royal Canadian Navy warships, while the centre of the space is dominated by a spherical, black naval contact mine and a large wartime photo of a busy Halifax naval base. |

|

| A display on the Second World War battle around convoy SC107 in October-November 1942. Departing from New York on 29 October, the convoy of 39 freighters escorted by two destroyers and six corvettes was attacked by 17 U-boats once beyond shore-based air cover. Fifteen of the freighters were sunk before the convoy came back under the protection of shore-based air cover in the eastern Atlantic. The disaster of convoy SC107 highlighted the flaws of the transatlantic convoy system, including poor equipment and training. On the far left of the display is the bell from HMCS Algoma, one of the corvettes escorting convoy SC107. |

|

| A model of the Royal Canadian Navy Flower Class corvette HMCS Ville de Quebec (K242). Ville de Quebec, built to an improved design with an extended forecastle for better seakeeping and higher quality equipment, was commissioned in 1943 and served on transatlantic convoy duty as well as in the Mediterranean, where she sank U-224 off Algiers on 13 January 1943. |

|

| On the left is a life jacket light useful in signalling the location of survivors bobbing in the water after being sunk on the treacherous convoy routes. On the right is the oil-stained life preserver worn by Lieutenant Commander TC Pullen of HMCS Ottawa following the torpedoing of the ship by U-91 on 13 September 1942. |

|

| A model of HMCS Victoriaville (K684), a River Class frigate commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy in November 1944. With higher speed, greater endurance, and heavier armament than the corvettes, frigates were more effective anti-submarine vessels but were not introduced into service until later in the Second World War. U-190 surrendered to Victoriaville on 11 May 1945 and was escorted to Bay Bulls, Newfoundland by the Canadian frigate. |

|

| A British Mk I contact mine, used by Allied navies in both the First and Second World Wars. The mine was detonated when a ship's hull crushed one or more of the protruding horns on the mine. Such contact mines were tethered to a sinker via a length of cable, held just below the water to avoid visual detection. |

|

| A display of wartime publications related to civil defence, an armband for Air Raid Precautions (A.R.P.) personnel, a Royal Canadian Navy children's colouring book, and ration booklets. |

|

| This display is devoted to the Second World War on the homefront in Halifax. It notes that Halifax held a trial blackout and air raid exercise on 5 September 1939, and that rationing was in full force by the end of 1941 in order to give priority for food and fuel to the armed forces. |

|

| A model of a Supermarine Stanraer flying boat, one of the early anti-submarine aircraft used to defend convoys and attack marauding German U-boats off the Atlantic coast of Canada. |

|

| A display on the convoys and the dangers they faced, including mines laid in harbour approaches, enemy submarines and surface raiders, and the North Atlantic weather. The map mounted in the centre of the display wall depicts the range of land-based air cover provided by the Royal Canadian Air Force coastal squadrons in eastern Canada and by Allied squadrons based in Iceland and the United Kingdom. In the foreground is a large model of the 10,000-ton freighter Point Pleasant Park, a typical example of the Park Boats built in Canada during the war; these freighters were equipped with defensive weaponry, a net against torpedoes, and a mine-sweeping capability. |

|

| A rum jug and tot measure used to issue the daily rum ration to navy sailors. The issuance of a rum ration dated back to the 1700s, when water would not keep for long periods of time at sea. As such, before the noon meal every day, rum would be transferred from wooden casks to wicker-encased jugs and taken to the petty officers and crew to be carefully measured out. The Royal Canadian Navy discontinued the rum ration in 1972. |

|

| A model of a Type VII U-boat, the mainstay of the German U-boat fleet during the Battle of the Atlantic. Type VII U-boats were able to stay on patrol for up to 10 weeks. Wolfpacks of such U-boats formed a patrol line across the anticipated route of a transatlantic convoy in the hope of detecting the slow-moving Allied freighters. Once one of the U-boats had detected the convoy, it shadowed and provided positional information via radio to permit the other U-boats of the wolfpack to home in for a coordinated mass attack on the convoy. |

|

| A large builder's model of the Royal Canadian Navy Wind Class icebreaker HMCS Labrador (AW 50), built by Marine Industries Ltd in Sorel, Quebec and commissioned on 8 July 1954. HMCS Labrador measured 82 metres (269 feet) in length, 19.2 metres (63 feet) in beam, with a draught of 9 metres (29.5 feet 10 inches) and a displacement of 6,490 tons at full load. The Arctic Class 2-3 vessel was powered by six 10-cylinder diesel engines, each producing 2,000 brake horsepower to propel the ship at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). The ship carried a crew of 224 and was equipped with a flight deck and hangar capable of accommodating either two single-rotor Bell HTL-4 helicopters or one Piasecki HUP-II twin-rotor helicopter. Although fitted to carry 40mm and 5-inch guns, these weapons were never installed. |

|

| HMCS Labrador is notable as the first warship to transit the Northwest Passage through the Arctic and the first ship to circumnavigate North America in a single voyage. However, she had a short service life with the Royal Canadian Navy, being transferred to the Department of Transport in November 1957 and being redesignated as Canadian Government Ship (CGS) Labrador. In 1962, Labrador was redesignated again as Canadian Coast Guard Ship (CCGS) Labrador when she joined the fleet of the newly established Canadian Coast Guard. After years of ice-breaking and hydrographic work, CCGS Labrador was taken out of service in 1987 and sold for scrapping in Taiwanin 1989. |

|

| A model of HMCS Bras d'Or (FHE 400), the world's fastest warship when commissioned on 23 July 1968. Designed as an experimental high-speed anti-submarine vessel, the surface-piercing hydrofoil design permitted a sustained speed of 63 knots (117 km/h; 72.7 mph). HMCS Bras d'Or was built by de Havilland Canada & Maritime Industries Ltd in Sorel, Quebec. She measured 46 metres (151 feet) in length and 6.6 metres (21.5 feet) in beam, with a displacement of 180 tons and a crew of 25. No weapons were fitted to this experimental craft, which suffered from high operating costs and technical defects. As a result, the Royal Canadian Navy laid up Bras d'Or in 1971 and decommissioned her in 1972. She is now on display at a maritime museum in L'Islet-sur-Mer, Quebec. |

|

| Model of Tribal Class destroyers of the Royal Canadian Navy. At top is HMCS Micmac (R10; DDE 214), one of eight British-designed Tribal Class destroyers operated by Canada during and after the Second World War. Micmac served between September 1945 and March 1964. The middle ship is HMCS Iroquois (DDG 280) as originally designed with a 5-inch deck gun and split funnels; she served between 1972 and 2015. The nearest model is of HMCS Athabaskan (DDG 282) as depicted following the Tribal Refit and Update Modernisation Program (TRUMP) which, amongst other changes, replaced the 5-inch gun with a 76-mm gun and trunked the angled funnels into a single block funnel for decreased infrared signature. Athabaskan served between 1972 and 2017, being the last of Canada's four 1970s-era Tribal Class destroyers to be decommissioned. The display showcases the evolution of the destroyer and its weapons between the 1940s and the 1990s. |

|

| The entrance to the exhibit devoted to the devastating Halifax Explosion of 6 December 1917. The photo on the entrance wall depicts Halifax's bustling industrial North End in the late-19th century, with coal being loaded aboard the cruiser HMS Ariadne and mills, factories, and wharves seen in the background. The North End was the epicentre of the explosion that wiped out this entire area in an instant. |

|

| A display charting the collision between the Norwegian freighter Imo and the French munitions ship Mont Blanc in Halifax harbour at 8:45 am on 6 December 1917. Sparks caused by the collision reached the 2,924.5 tons of high explosives and barrels of gasoline stowed aboard Mont Blanc, causing the crew to abandon ship and row frantically for shore. Huge crowds gathered by the shore as an enormous column of black smoke rose over the harbour, with flames leaping skyward. The derelict and flaming Mont Blanc drifted towards Halifax, coming to rest at Pier 6. A few seconds before 9:05 am the munitions aboard Mont Blanc detonated. The explosion was so powerful that it was felt 483 kilometres (300 miles) away, shattered glass 100 kilometres (62 miles) away, and utterly devastated a large portion of Halifax. A thick fog of vaporised fuel and chemical by-products fell as rain over the immediate area, wand additional fires were sparked by wood ovens and stoves in homes overturned by the force of the explosion. |

|

| Some of the personal items found on bodies of those killed in the Halifax Explosion. Bodies were taken to the Chebucto Road School in Halifax, pressed into service as the mortuary. Some bodies were embalmed if identification was thought likely. The mortuary was open 13 hours each day for survivors to come and identify deceased family and friends. Those coming to the mortuary were interviewed before being allowed to view bodies matching the descriptions they had provided. Troops searching the rubble and wreckage sent notes with each body, providing as much information as possible and including any personal effects found with the bodies in order to aid in identification. |

|

| The wallet, watch, and pen belonging to Vincent Coleman, as well as the telegraph key he used on the morning of 6 December 1917. Coleman was the telegraphist at the railway yard in Richmond, the North End neighbourhood of Halifax that was obliterated by the explosion aboard the Mont Blanc. Coleman, who worked only a few hundred feet from Pier 6, where the Mont Blanc drifted after colliding with Imo, desperately tapped out a telegraph warning to other railway stations to alert them to the dangerous cargo aboard the Mont Blanc so that incoming trains could be halted. Coleman was killed in the explosion but his message got through to every station between Halifax and Truro, Nova Scotia. Alerted to the disaster, the Canadian Government Railway stopped trains bound for Halifax, thus preventing even more casualties. Additionally, with the advance warning provided by Coleman, railway authorities were able to respond quickly with six trains containing relief supplies and firefighters and medical personnel arriving in Halifax on the day of the explosion. Coleman's telegraph key was found on his body and given to his widow, who donated it to the Public Archives of Nova Scotia; it was transferred to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in 2004. |

|

| A display of pieces of jagged, twisted metal debris from the hull of the Mont Blanc. The ship was loaded with barrels of benzol stowed in the deck and almost 3,000 tons of ammunition in the cargo holds. When the benzol caught fire from sparks caused by the collision with Imo, the fire soon spread to the cargo holds, igniting the high explosives. The sudden, violent chemical reaction released an enormous amount of energy, which tore through the ship at 1,500 metres (4,921 feet) per second. The force of the explosion was equivalent to a three-kiloton bomb. A gun barrel being carried aboard Mont Blanc was thrown more than 5.5 kilometres away, while a 517 kilogram metal chunk of one of the ship's anchors was found over three kilometres from the site of the explosion. Pieces of wreckage resulting from the Halifax Explosion continue to be unearthed up to the present day as a result of erosion or frost heaves. |

|

| Fragments of wreckage from the Mont Blanc, found scattered in different locations of Halifax following the explosion. |

|

| The Halifax Explosion caused 1,690 immediate deaths, with over 9,000 others injured, and over 6,000 made homeless. Seven ships in the harbour were destroyed, along with 1,630 buildings n Halifax; another 12,000 buildings were damaged. Temporary homes, funded largely by the State of Massachusetts, were constructed by spring 1918. Of the crews of the two ships involved in the deadly collision, the captain, pilot, and five of 39 crewmen aboard Imo were killed, while only one of the crew from the Mont Blanc died. |

|

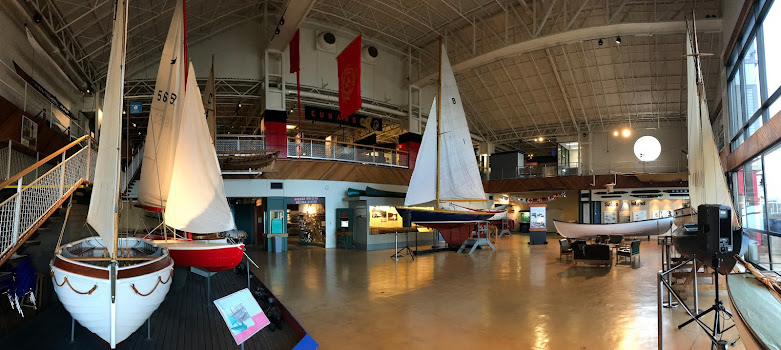

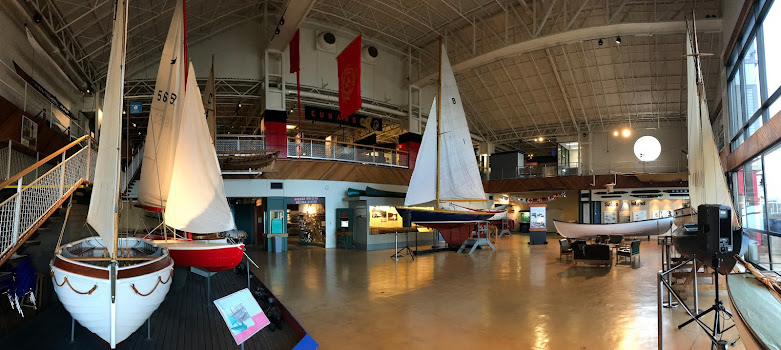

| The small craft gallery, containing a number of historic small craft from Atlantic Canada's rich maritime heritage. |

|

| Several sailing dinghies on display. On the left is a 4.3 metre (14.25 foot) clinker-built naval sailing dinghy from the pre-Second World War period. The red boat is the snipe class sloop Ripple, built in Halifax in 1945 and measuring 4.72 metres (15.5 feet) in length. To the right of Ripple is the clinker-built Morse dinghy D-4, built in Shelburne, Nova Scotia in c. 1950 and measuring 4.3 metres (14 feet) in length. The boat on the far right is the clinker-built Alden class X dinghy Sally Anne, built in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1934. |

|

| A Bluenose class sloop built in 1945 in East Chester, Nova Scotia. Originally named Gilpie, and later Vagabond, this vessel measures 7.2 metres (23 feet 5 inches) in length and 190.5 centimetres (6 feet 3 inches) in beam, with a draught of 71.12 centimetres (2 feet 4 inches). This Bermuda-rigged sailing vessel was designed by William J. Roué, the designer of the famous schooner Bluenose (depicted on the Canadian 10 cent piece), and shares the larger vessel's sweeping lines. Gilpie/Vagabond is the only sailing vessel in the museum's collection to have a ballast keel (it is made of lead). |

|

| Saucy Sue, a gasoline-powered former lobster boat owned by Percy Weir, Commodore of the Royal Western Nova Scotia Yacht Club in Digby, Nova Scotia. This vessel, built in Bear River, Nova Scotia around 1920, was converted into a chartered fishing vessel sometime in the 1930s through the addition of a raised forecastle to provide more room in the fore-cabin. Saucy Sue is of carvel-planked construction, measuring 7.9 metres (26 feet) in length, 193 centimetres (76 inches) in beam, and with a draught of 95.6 centimetres (38 inches). |

|

| The Malti Pictou canoe, made of birchbark and measuring 4.7 metres (15.5 feet) in length. Mi'kmaq chief Malti Pictou of Bear River, Nova Scotia and, later, his brother Matthew, used this canoe to hunt porpoises in the Bay of Fundy between 1890 and 1920. The oil in the porpoises' blubber provided a source of income for the Mi'kmaq. In 1936, Matthew Pictou re-enacted a traditional porpoise hunt using this canoe for a series of photos and a film, Twilight of Micmac Porpoise Hunters, by Dr Alexander Leighton. The film, photographs, and canoe were donated to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic by Dr Leighton in 1975. |

|

| A clinker-built, double-ended, self-bailing Sable Island lifeboat or rescue boat. Based on land, the wheeled wagon was used to tow the boat near the scene of a shipwreck. A cork-filled space beneath the boat's deck made it virtually unsinkable if damage was incurred during a rescue operation. The pointed ends allowed the boat to better handle rough surf, and the use of sweep, which could be pulled inboard in rough weather, instead of a fixed rudder also served to avoid damage. This boat measures 7.7 metres (25.2 feet) in length, 233.7 centimetres (92 inches) in beam, and with a draught of 91.4 centimetres (36 inches), and could be powered by either oars or sail. |

|

| The entrance to the 'Age of Steam' gallery on the upper floor of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. This gallery houses a fascinating collection of model steamship and artefacts from the Cunard Line. |

|

| A model of the wooden paddle steamer RMS (Royal Mail Ship) Britannia, the first ship built for the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, founded by Halifax-born Samuel Cunard. The company's unwieldy name would later be changed to the Cunard Steamship Company, reflecting Samuel Cunard's visionary role. The 1,100-ton Britannia was launched in February 1840 and departed Liverpool on its maiden voyage to Boston, Massachusetts via Halifax, on 4 July 1840. The ship carried 90 crew and 63 passengers, including Samuel Cunard and his two daughters. After a transatlantic voyage of 12 days and 10 hours, Britannia arrived in Halifax on 17 July. Britannia's welcome upon arrival in Boston was rapturous, with Cunard receiving 1,873 invitations to dinner from notable Bostonians. The ship's homeward passage from Halifax to Liverpool took only 10 days, a record that stood until 1842. Britannia's voyage marked the start of the Age of Steam in the North Atlantic. |

|

| A model of the SS Dunottar Castle, built by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Ltd in Glasgow, Scotland in 1890. Constructed at the dawn of the steamship era, Dunottar Castle was powered by a triple-expansion steam engine but her cautious owners also had her rigged as a three-masted schooner for sailing in the event of mechanical problems. The ship was built for the Castle Line and designed to outdo the competing Union Line on the Southampton, UK to Cape Town, South Africa route, being bigger, faster, and more comfortable for passengers than any other vessel on that route. During the Boer War in 1899, Dunottar Castle transported troops and other passengers to Cape Town, including the young war correspondent Winston Churchill. In 1913, the ship was sold to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company and renamed Caribbean. During the First World War, Caribbean was requisitioned as a troop ship, sailing to Europe with Canadian troops aboard in the first Canadian convoy of the war in 1914. The next year, Caribbean was assigned to transport dockyard workers to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands but foundered in bad weather off Cape Wrath in northern Scotland. Royal Navy ships rescued all but 15 men from Caribbean before she sank on 27 September. The 5,465 gross ton Dunottar Castle/Caribbean measured 120 metres (420 feet) in length and 14.9 metres (49 feet) in beam, with accommodations for 160 First Class, 90 Second Class, and 100 Third Class passengers, or 1,200 troops. |

|

| A view of some of the artefacts, models, and other displays in the museum's 'Age of Steam' gallery. |

|

| The Visible Storage area of the museum, where visitors can see some of the artefacts in the museum's collections which are not displayed with curation. |

|

| A model of the German armed merchant cruiser Atlantis, formerly SS Goldenfels, arguably the most successful such raider of either the First or Second World Wars. Armed merchant cruisers were disguised cargo vessels with hidden armament which freely ranged the world's oceans hunting down and destroying unsuspecting enemy merchant vessels. The 7,862-ton Goldenfels was built for Germany's Hansa Line in 1937 but was converted into an armed merchant cruiser by the German navy in late 1939. The work included the installation of six 5.9-inch guns, one 75mm gun, one twin 37mm gun, four 20mm guns, four single 21-inch torpedo tubes, 92 mines, and facilities for two Heinkel 114 (and later Arado 196) seaplanes. These weapons were either stowed on deck disguised as cargo or in the ship's holds, where they could be quickly brought into action. Fuel and water capacity was increased to permit long sea voyages without resupply, and accommodations for the raider's 347 crew (far larger than the ship was originally designed for) were installed. In her career as a raider, Atlantis steamed more than 102,000 miles in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, during which time she captured or destroyed 22 Allied ships with a combined tonnage of 145,697. During these voyages, Atlantis's crew disguised the ship to impersonate Allied or neutral freighters, such as the Dutch ships Brastagi and Abbekerk and the Norwegian Tamesis. This was accomplished through the erection of dummy funnels, ventilators, derrick posts, and masts, as well as dressing a member of the crew on occasion to look like the captain's wife. Atlantis's final voyage, lasting 622 days, commenced on 31 March 1940 and ended when she was sunk by the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Devonshire off Ascension Island on 21 November 1941. The raider Atlantis measured 148.8 metres (488.1 feet) in length, with a beam of 18.7 metres (61.3 feet), and a draught of 9.5 metres (31.1 feet). |

|

| In the foreground, a model of the SS Lady Rodney, one of five 'Lady Boats' built for Canadian National Steamships Ltd in the late 1920s. The 8,194 gross ton Lady Rodney was built by Cammell Laird & Company in Birkenhead, England and measured 126.5 metres (415 feet) in length, with a beam of 18.3 metres (60 feet) and a draught of 10 metres (32 feet 9 inches). Her top speed was 15 knots (27.8 km/h). Carrying passengers and freight from Halifax and Montreal to the West Indies up to the start of the Second World War, Lady Rodney was requisitioned by the Canadian government for use as a troop ship. Having survived the war, the ship was first used to transport war brides to Canada and then reverted to service between Canada and the West Indies. Sold to Egypt's United Arab Line in 1953 and renamed Mecca, the ship continued in service until 1967, when the Egyptians scuttled her in the Suez Canal in an effort to disrupt Israeli shipping traffic. |

|

| A model of SS Nova Scotia, a 6,796 gross ton liner built in 1926 by Vickers Sons & Maxim Ltd in Barrow-in-Furness, England for the firm of Furness, Withy & Co. of Liverpool. Originally serving the transatlantic mail route between Liverpool and Boston via St. John's, Newfoundland and Halifax, the ship was requisitioned as a troop transport in early 1941. In the early morning of 28 November 1942, while steaming off the east coast of South Africa with 750 Italian prisoners of war and civilian internees and 3,000 bags of mail destined for Durban aboard, Nova Scotia was hit by three torpedoes fired from U-177. Within 10 minutes, Nova Scotia caught fire, rolled to port, and sank by the bow. A Portuguese frigate based in Lourenço Marques, Mozambique responded to the disaster, arriving on the scene of the sinking the next day. Although 130 Italian internees, 42 guards, 17 crew members, three military and naval personnel, one gunner, and one passenger were rescued, 858 others died from drowning or shark attack. SS Nova Scotia measured 123.8 metres (406.1 feet) in length, with a beam of 16.9 metres (55.4 feet), and a draught of 10.46 metres (34 feet 4 inches). Her quadruple-expansion steam engine drove Nova Scotia at a top speed of 15 knots (27.8 km/h) and she carried a crew of 113 in 1942. |

|

| A model of the SS Montroyal, built in 1906 by the Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Company Ltd in Glasgow, Scotland for the Canadian Pacific Railway Ocean Lines and originally named Empress of Britain. Empress of Britain was the first of the 'Empresses of the Atlantic' liners built for Canadian Pacific. She achieved a Canadian record crossing time of five days, 18 hours, and 18 minutes between Liverpool and Halifax on her second voyage. During the First World War, Empress of Britain was requisitioned by the British Admiralty as a patrol ship and troop transport, being re-sold to Canadian Pacific at war's end. Plying the route between Quebec City and Liverpool, the ship was renamed Montroyal in 1924 to free up the name Empress of Britain for a new ship being constructed for Canadian Pacific. In 1930, Montroyal was sold to Norwegian shipbreakers. The 15,850 gross ton ship measured 173.7 metres (569 feet 9 inches) in length, with a beam of 20 metres (65 feet 9 inches) and a draught of 12.2 metres (40 feet). Her engines, producing 18,000 horsepower, and twin screws propelled her at a speed of 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h). |

|

| The SS Duchess of York, built in 1929 by John Brown & Company, Clydebank, Scotland for the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The 20,000 gross ton Duchess of York measured 181.7 metres (596 feet) in length, with a beam of 22.9 metres (75 feet), and a draught of 16.2 metres (53 feet). With engines producing 18,000 horsepower, her top speed was 18 knots (33.3 km/h). |

|

| The models of SS Duchess of York, SS Montroyal, and SS Nova Scotia in large glass cases. |

|

| A 1:96 scale diorama depicting Canadian Scientific Ship (CSS) Acadia on her first mission to Canada's northern waters in 1913. |

|

| A model of CSS Acadia, built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd in Newcastle, England in 1913 for the Government of Canada. Designed specifically for hydrographic surveying in northern waters, CSS Acadia was launched on 8 May 1913 and spent most of her career charting new areas and updating navigational charts for the Northumberland Strait, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the coast of Newfoundland. The ship served as a commissioned patrol and training vessel of the Royal Canadian Navy during both the First and Second World Wars and was only taken out of government service in 1969. Formerly berthed at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, CSS Acadia was transferred to the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in August 1981 and now resides at a jetty adjacent to the museum on Halifax Harbour. In 1976, CSS Acadia was designated as a National Historic Site of Canada. The 846 gross ton CSS Acadia measures 55 metres (181 feet 9 inches) in length, with a beam of 10.2 metres (33.5 feet) and a draught of 3.7 metres (12 feet). Her peacetime crew complement was 50. She was powered by a 1,200 horsepower triple-expansion steam engine driving a single propeller, with a top speed of 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h). |

|

| A 1:96 model of the former CSS Acadia, shown as she appeared as the Royal Canadian Navy's HMCS Acadia in the Second World War when she patrolled the approaches to Halifax Harbour in 1940-41. Acadia is the only surviving ship to have served the Royal Canadian Navy in both World Wars. |

|

| The entrance to the exhibit on Samuel Cunard and the Cunard Line, in the museum's Age of Steam gallery. Samuel Cunard was born in Halifax in 1787 and lived most of his life in the city. His entrepreneurial talent was demonstrated in the range of jobs he pursued in colonial Nova Scotia, including selling timber overseas, trading local goods for tropical produce from the West Indies, whaling voyages, developing coal mining, and building and operating ships. Cunard is best remembered for founding the British and North American Steam Packet Company, later renamed the Cunard Steamship Line, which revolutionised transoceanic travel by combining the regularly of scheduled sailing packets with the innovation of steam engine technology to provide faster, safer, more reliable, and more comfortable connections across the oceans. |

|

| A model of the SS Royal William, a steam-powered paddle wheel steamer commissioned by a group of British North American investors, including Samuel Cunard, in 1833 to improve communications between Quebec City and Halifax. Built in Cap Blanc, Quebec, Royal William entered service with the investors' Quebec and Halifax Steam Navigation Company; however, the St Lawrence route proved unprofitable and the investors sought buyers for the ship in Europe. To market the vessel to potential buyers, Royal William was sailed from Pictou, Nova Scotia to Gravesend on the River Thames in England in August 1813, making the voyage almost entirely under steam power in a voyage of 25 days. The ship was eventually bought by the Spanish Navy renamed Isabel Segunda, and served until being driven ashore and wrecked at Algeciras on 8 January 1860. Although Royal William did not succeed in its intended market, she demonstrated the practicality and potential of steamships on transoceanic routes and contributed to Cunard's later founding of the successful British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. |

|

| A large model of the famous Cunard ocean liner RMS Mauretania, sister to the ill-fated RMS Lusitania. When launched in 1906, these ships were the largest and fastest ships in the world. Mauretania set a record for the fastest westbound transatlantic voyage in 1909, a record that would stand until 1929. While Mauretania enjoyed a long, 28-year service career with Cunard, her sister ship Lusitania met an early demise 18 kilometres off the southern coast of Ireland on 7 May 1915 after being torpedoed by German submarine U-20, resulting in the deaths of 1,198 passengers and crew. The deaths of 124 Americans aboard Lusitania was one of the catalysts for the US decision to enter the war on the side of the Entente powers; although Canada was already at war with Germany, the 170 Canadians who perished in the Lusitania sinking hardened anti-German sentiment in Canada. Much to the disappointment of her devoted passengers over the years, Mauretania was retired in September 1934 and scrapped the next year in Rosyth, Scotland. The success of the Mauretania and Lusitania on the North Atlantic provoked Cunard's competitor, White Star Line, to build the Olympic and Titanic. |

|

| RMS Mauretania visited Halifax 23 times during her career, including as a troop transport during the First World War. After the war, Mauretania returned to liner service, being painted white in 1930 when she was shifted to cruising in warm southern waters; the white paint reflected the hot tropical sun, providing a more comfortable temperature inside for passengers. In addition to her famous speed, Mauretania was also the epitome of luxury, featuring 28 different types of decorative wood in her sumptuous interior decor. This 1:48 scale model of Mauretania is the largest antique model in Canada and was actually originally built as sister ship Lusitania; when Lusitania was sunk in 1917, the model was converted into Mauretania and was later repainted in the white hull colour scheme used by the ship in the 1930s. The model was installed in its current location in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in 2011 using a forklift. |

|

| The Cunard exhibit. |

|

| A display of Cunard Line artefacts, the centrepiece of which is the ship's wheel from RMS Aquitania. When Aquitania was scrapped in 1950, the wheel was presented by Cunard to the City of Halifax in recognition of the city's long association with the ship. Aquitania, which served between 1914 and 1950, transported troops from Halifax to Europe during both World Wars, was used to transport Canadian soldiers home after the Second World War, and brought war brides and migrants to Canada via the port of Halifax during her last years in service. |

|

| The 'cube' design tea service from the Cunard ocean liner RMS Aquitania. This set was presented to Halifax Harbour pilot 'Mont' Power in 1940 after he was forced to remain aboard the ship all the way to New York due to adverse weather conditions which prevented him from disembarking after Aquitania had cleared Halifax Harbour. |

|

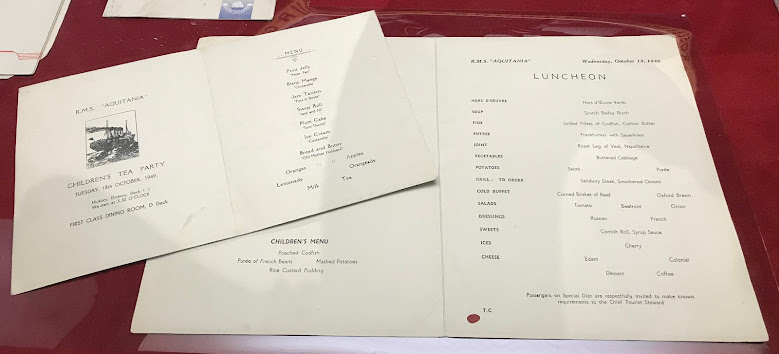

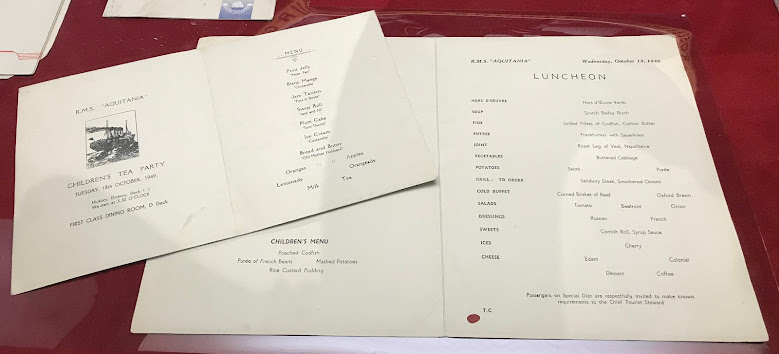

| Two menus from RMS Aquitania: a children's tea party menu from 18 October 1949 and a luncheon menu from 19 October 1949. |

|

| A cutaway model of RMS Aquitania, showing the lengthwise internal deck layout. Aquitania was built by John Brown & Company, Clydebank, Scotland for the Cunard Line and entered service on 30 May 1914. The ship provided continuous passenger service on the Southampton-Cherbourg-New York route from 1920 to 1939, and was used as an armed merchant cruiser, hospital ship, and troop ship during both World Wars. Aquitania's last years of service were spent transporting war brides and other immigrants to Halifax's Pier 21 to start a new life in Canada. The 45,650 gross ton RMS Aquitania measured 275 metres (902 feet) in length, with a beam of 30 metres (97 feet), and a draught of 16.6 metres (54.5 feet). Her steam turbines generated 59,000 horsepower and four propellers drove Aquitania at a service speed of 24 knots (44 km/h). With 10 decks, Aquitania could carry 3,230 passengers in 1914 (lowered to 2,200 in 1926), as well as a crew of 972. |

|

| A typical ocean liner deck chair at the heart of the Cunard exhibit, flanked by large models of some of Cunard's most famous ships and other artefacts and information boards. |

|

| A model of RMS Carinthia, one of four Cunard Line Saxonia Class ships (along with Franconia, Carmania, and Sylvania) in regular service on the Liverpool-Montreal-Halifax route. The 21,989 gross ton Carinthia was built by John Brown & Company, Clydebank, Scotland and completed in 1956. She served with Cunard until 1968, when she was sold to the Sitmar Line, rebuilt into a dedicated cruise ship, and renamed SS Fairsea. Later sold to P&O and then China Sea Cruises, the ship (by then named SS China Sea Discovery) was scrapped in India in 2005-06. As built, Carinthia measured 185.4 metres (608 feet 3 inches) in length, with a beam of 24.4 metres (80 feet), and a draught of 8.7 metres (28 feet 7 inches). Her four steam turbines produced 24,510 horsepower, powering four propellers that drove Carinthia at a service speed of 19.5 knots (36.11 km/h) or a top speed of 25 knots (46 km/h). RMS Carinthia carried 868 passengers and a crew of 461. |

|

| A model of the Canadian Government Railways ferry SS Prince Edward Island. The 2,795 gross ton vessel was built in Newcastle, England in 1914 and provided the first railway link across the Northumberland Strait between Prince Edward Island and the Canadian mainland. The ferry could accommodate 12 rail cars, and her additional propeller forward made her an effective icebreaker. Although retired in 1931 after 16 years of service, SS Prince Edward Island was returned to service in 1941 following the sinking of her replacement, SS Charlottetown, off the coast of Nova Scotia. SS Prince Edward Island remained in service until 1969. She measured 87 metres (285.3) feet in length, with a beam of 15.9 metres (52.3 feet), and a draught of 6.5 metres (21.3 feet). |

|

| The Canadian Government Ship (CGS) N.B. McLean, built by Halifax Shipyards Ltd in 1930. She was the first icebreaker to be built in Nova Scotia and the world's second largest icebreaker when she entered service with the Department of Transport's Marine Service, which later became the Canadian Coast Guard in 1962. Much of the N.B. McLean's service life was spent in the waters of the Eastern Arctic and Canada's Atlantic provinces. The forward part of the ship's reinforced hull was designed to ride up over the ice and break it. After 49 years of service, CGS N.B. McLean was retired in 1979 and scrapped in Taiwan in 1988. The 3,254 gross ton CGS N.B. McLean measured 79 metres (260 feet) in length, with a beam of 18 metres (60 feet), and a draught of 6.1 metres (20 feet). She was powered by two triple-expansion steam turbines producing 6,500 horsepower to propel the ship at 15 knots (28 km/h). |

|

| A model of the CGS Lady Laurier, a cable ship built in 1902 and designed to maintain the underwater telegraph cable between Halifax and the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, as well as tend to lighthouses and buoys in the area. Lady Laurier spent her career in the waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and off the coasts of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. In the Second World War, the ship was responsible for laying all of the war channel buoys for the Royal Canadian Navy in the ports of Shelburne, Halifax, Sydney, and St. John's. Decommissioned in 1960, Lady Laurier was scrapped at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. The 1,051 gross ton CGS Lady Laurier measured 65.5 metres (214.9 feet) in length, with a beam of 10.4 metres (34.2 feet), and a draught of 5.5 metres (18 feet). |

|

| A model of the SS Wabana, an ore carrier built in Britain in 1911 and employed to carry iron ore from Labrador. To speed loading, Wabana featured giant hinged hatch covers that could be swung open to receive ore; most freighters of that era used planks and heavy tarps to cover their hatches. Purchased later by a steel company in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Wabana was used to haul coal and iron ore and made frequent port calls at Halifax. Renamed Canby, the ship was wrecked on Guyon Island, located off the east coast of Cape Breton Island, on 19 February 1934. |

|

| A model of the SS Lord Kelvin, a cable ship built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson Ltd in England in 1916. The 2,641 gross ton ship spent her career laying telegraph cables until retired in 1963. Her most dramatic escapade came on 27 September 1942, when she accidentally rammed the Royal Canadian Navy Bangor Class minesweeper HMCS Chedabucto whilst being escorted to Rimouski, Quebec in the early morning and in blackout conditions. With a 6.1-metre hole in her side Chedabucto began to take on water and her crew were evacuated to Lord Kelvin. Although the cable ship attempted to tow Chedabucto to Rimouski, the minesweeper sank en route. Lord Kelvin was repaired and returned to service. She was scrapped at La Spezia, Italy in 1967. SS Lord Kelvin was powered by two triple-expansion steam engines which propelled the ship at 11 knots (20 km/h). She measured 96.5 metres (316.6 feet) in length, with a beam of 12.6 metres (41.2 feet), and a draught of 6.9 metres (22.7 feet). |

|

| Looking down into the small craft gallery on the lower level of the museum. |

|

| The Shipwrecks and Treasures gallery recounts a number of famous shipwrecks off the coast of Nova Scotia and efforts to discover their secrets and recover their artefacts. |

|

| A map depicting the location of shipwrecks in Nova Scotian waters, which number over 10,000 and could be as high as 25,000. |

|

| A display on the wreck of HMS Tribune, a 916 ton frigate armed with 34 guns. Originally built by the French at Rochefort in 1794 and named La Tribune, the ship was captured by the British in 1796 and renamed HMS Tribune. Such frigates were ideal for service in North America, being both fast and sufficiently armed to overwhelm any threats found in local waters. HMS Tribune ran aground at the entrance to Halifax Harbour on 23 November 1797 after her overconfident captain refused a local pilot. Expecting the rising tide to lift his ship off the rocks, the captain also turned away rescue boats sent to take off the crew. A rising gale blew Tribune further onto the rocks in Herring Cove and over 100 of the crew sought refuge in the ship's rigging. Of over 240 crew aboard Tribune, only 14 survived the disaster, including two rescued by a local teenager using a small rowing skiff. Amongst the artefacts recovered from the wreck are brass nails, a Royal Navy sailor's belt buckle, elements of a British sea service pistol, a gun flint, coins, a cannonball for one of Tribune's 32-pound carronades, a candlestick, a pulley, and a cutlass scabbard. Hanging from the top of the display is HMS Tribune's bell, discovered in 1855 by salvagers working on another wreck and used as the church bell in St. Paul's Catholic Church in Herring Cover until transferred to the museum in 1924. |

|

| A display on the wreck of the White Star liner SS Atlantic, which sank near Halifax on 1 April 1873 with heavy loss of life. Until the sinking of the Titanic, the loss of the Atlantic was the worst ocean liner disaster in history. Built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast in 1871, the 3,707-ton Atlantic measured 128 metres (420 feet) in length and featured both a steam engine and full sailing rig. SS Atlantic was en route to New York from Liverpool but was forced to divert to Halifax due to bad weather. Despite being unfamiliar with the Nova Scotia coast, the ship's captain took few precautions and, several miles off course, sailed Atlantic directly onto the rocky coastline at 3:00 am. Although the crew and local villagers attempted a rescue operation, 562 of the 933 people aboard the ship drowned in the surging, freezing surf. Although the ship was smashed to pieces by heavy wave action, salvagers recovered a number of items now on display here, including a silver pitcher and dish covers, dishware, a bulkhead clock, a bible, a clothes brush, one of the ship's life rings, a fork, a brooch, a small statue of the Virgin Mary, an ornamental lamp holder, a lady's glove, a kettle, a pair of binoculars, and an interior window frame. |

|

| A display on the sinking of the 4,738 gross ton Cobequid, originally built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast in 1893 for the Union Line and named Goth. The 134.1 metre (440 foot) ship was sold to the Royal Mail Steam Packet Line in 1913 and renamed. A medium-sized ocean liner, Cobequid operated between Canada and the West Indies. On 13 January 1914, after an uneventful voyage from the West Indies, Cobequid ran aground near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. The ship's captain later blamed the disaster on a misplaced navigational buoy. The passengers and crew aboard Cobequid were rescued by the small coastal steamers Westport and John L. Cann. After everyone had been saved, a horde of scavengers in small boats picked the wreck clean of any items of value, including Cobequid's grand piano, which was allegedly taken away in a small open boat. The display contains a few of the items scavenged from Cobequid, including a tablecloth and a coverlet from a cabin bed, which bears the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company crest. On the left is one of the wooden washstands known to have been salvaged from Cobequid, with soap dishes, holders for drinking glasses, and hooks for towels. |

|

| A model of His Majesty's Hospital Ship (HMHS) Letitia. Built as an ocean liner for the Anchor Donaldson Line in 1912 and operated on the Glasgow-Quebec City-Montreal route, the ship was requisitioned by the British Admiralty in 1914 and converted into a hospital ship. After an eventful career as a hospital ship, including coming under fire while evacuating wounded troops from the Dardanelles, Letitia's end came on 1 August 1917 when the Halifax harbour pilot mistakenly navigated the ship onto the rocks at Portuguese Cove near the harbour entrance during a period of heavy fog that had impaired his ability to accurately determine the ship's position. Naval vessels arrived quickly and managed to safely evacuate all those aboard Letitia, including 546 wounded Canadian soldiers; however, one of the ship's stokers was accidentally left behind and drowned while trying to swim to shore. The 8,991 gross ton Letitia was built in Greenock, Scotland by Scott's Shipbuilding and Engineering Company Ltd and measured 143 metres (470 feet) in length. |

|

| A display on the shipwrecks of Louisbourg, the French fortress on Nova Scotia's Cape Breton Island. Established in 1713 to protect France's possessions in North America, Louisbourg was subjected to sieges by British forces in 1745 and 1758. During these operations, a number of ships were scuttled or sunk in battle, including some of the largest wooden warships ever sunk in Canadian waters. The large object in the display case in the centre of the photo is a bronze pump barrel, used to pump water out of the bilges of a ship. Based on the dimensions of this pump barrel, researchers were able to confirm it came from the 64-gun French warship Célèbre, which was sunk in flames in Louisbourg's harbour on 21 July 1758. She was one of four large French warships sunk in the harbour during the 1758 siege. |

|

| Part of a display on the treasure wrecks of Cape Breton Island, or Isle Royale as it was known to the French. Several shipwrecks of the 18th century contained large quantities of payroll money or personal fortunes. Treasure hunters were required to remit to the Nova Scotia government 10 percent of any treasure discovered, with the remaining 90 percent theirs to keep or sell. As a result of treasure hunters also being required to undertake some archaeology work under a heritage work permit, other non-treasure items have also been recovered from these wrecks. An example is the breach-loading French swivel gun mounted in this display, one of several which were used on the French armed transport Chameau. (Over 240 years of constant erosion by the waves have smoothed the brass gun.) Chameau was transporting payroll money and important officials from La Rochelle, France when she ran aground in a gale on 26 August 1725, killing all 300 people aboard. The wreck was only discovered in 1966, after which Nova Scotia became a hotspot for treasure hunters seeking a similar lucrative find. |

|

| A collection of 18th century French coins recovered from the wreck of the Auguste, a merchant ship hired after the British victory over the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1763. The Auguste was transporting French soldiers and officials back to France when weeks of westward winds blew the ship onto the rocks near the village of Dingwall on Cape Breton Island. Only seven of those aboard made it safely to shore. The coins were amongst the personal savings of those aboard the doomed Auguste, and bear a range of dates from the last years of the French empire in North America. |

|

| A 1:196 model of the White Star liner RMS Titanic, victim of the world's best-known maritime disaster. The 46,328 gross ton Titanic was built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast and measured 269.1 metres (882 feet 9 inches) in length, with a beam of 28.2 metres (92.5 feet) and a draught of 10.5 metres (34 feet 7 inches). Carrying 2,435 passengers and 892 crew, Titanic was described as virtually unsinkable, which explains why her 20 lifeboats could only accommodate a maximum of 1,178 people. As the nearest major port to the site of the Titanic sinking, Halifax was preparing to welcome the ship and its passengers after initial reports suggested that Titanic had only been damaged. When it was confirmed the ship had sunk, survivors were taken directly to New York while Halifax became the reception centre for 209 bodies of those who had drowned. |

|

| Part of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic's Titanic gallery, which traces the history of the ship from its construction to its loss on the night of 14-15 April 1912. The display seen here on the right describes Titanic's riveted steel construction, noting that Canadian scientists have discovered that the ship's steel plates contained high levels of sulphur, which made them brittle in cold temperatures, such as those in the North Atlantic; this could explain why the damage caused when Titanic collided with the iceberg was so extensive. |

|

| A deck chair from Titanic, recovered by the crew of the cable ship Minia and presented to Reverend Henry W. Cunningham to acknowledge his work performing memorial and burial services for Titanic victims brought aboard Minia. The chair, made of mahogany and other hardwoods, bears a carved five-pointed star which was the symbol of Titanic's owner, the White Star Line. The wicker seat has been re-caned using the same pattern, based on a piece of deckchair wreckage salvaged after the sinking. Such deckchairs had to be rented by passengers and, in 1912, were only available to those passengers in First or Second Class; passengers often tipped deckchair attendants extra to reserve a seat in a desirable location on deck. When Titanic sank, dozens of her deckchairs were thrown overboard in the hope that those who clung to them would be saved from drowning. |

|

A display on the White Star Line, noting its poor safety record in the years leading up to the Titanic sinking, including the loss of the SS Atlantic, along with 562 of those aboard, on 1 April 1873 off the coast of Nova Scotia. The display holds samples of White Star menus, silverware, a 1907 silver plate ashtray with the White Star insignia, a White Star Line Elkington silver plate First Class sauce bowl, and First Class china.

|

|

| A closer look at the White Star Line First Class china and glassware of the kind that would have been used aboard Titanic and her sister ship Olympic. The demitasse cup and saucer has the 'tongue and tendril' pattern developed for first class passengers. These items, as well as the liqueur glass, belonged to a Halifax dockworker and were likely a gift from RMS Olympic during one of the ship's many port visits to Halifax during the First World War. |

|

| A carved wooden panel from above the curved aft doorway into Titanic's First Class lounge. Furnished with Louis-Quinze furniture copied from the Palace of Versailles in France, the First Class lounge often hosted musical recitals; the musical motif in the panelling is nod to this. This panel fragment was recovered by the cable ship Minia, which responded to the Titanic sinking, and was kept as a memento by Minia's captain, William George Squares de Carteret. Its preservation was funded by the Titanic Historical Society. |

|

| A newel-post from one of the landings of Titanic's famously ornate First Class Grand Staircase, made from quarter-cut oak, the finest cut of the tree. The newel-post was kept by the captain of the cable ship Minia, William George Squares de Carteret. A fibreglass replica on the right permits museum visitors to feel the intricacy of the carving. |

|

| A display of dishes from steamships, recovered from Halifax Harbour by diver Greg Cochkanoff. For generations, sailors disposed of trash, including broken crockery, in the harbour. These shards and fragments contain the crests of a diverse range of steamship companies, from well-known firms like White Star and Canadian Pacific to dozens of lesser-known lines, as well as naval vessels. The map of the harbour shows the location where each of the displayed fragments was found. |

|

| A closer look at some of the crockery fragments discovered on the bottom of Halifax Harbour. From left to right: a fragment of a chamber pot from the Allan Line (1854); an Allan Line soup bowl (1865); a fragment of a serving bowl from the Mississippi & Dominion Steamship Company Ltd (1872); and a fragment from a soup bowl from the Hamburg America Line (1890). |

|

| A view of the rear, waterfront side of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic after closing time. |

|

| A port view of CSS Acadia, built in 1913 for the Government of Canada's hydrographic surveying efforts in northern waters. Now preserved as a museum ship in the collection of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Acadia retains her original engines, boilers, and crew accommodations little changed since her launch, making her one of the best preserved Edwardian-era ocean steamships. (Photo taken 25 April 2018) |

|

| A starboard quarter view of CSS Acadia moored in Halifax Harbour. As a commissioned Royal Canadian Navy vessel during the First World War, Acadia was in Halifax Harbour inspecting ships for contraband cargo on 6 December 1917. Acadia signalled the freighter SS Imo to proceed to sea, after which Imo collided with the ammunition ship Mont Blanc. The resulting catastrophic explosion decimated a large part of Halifax, though Acadia was spared serious damage as she was anchored four kilometres away. (Photo taken 25 April 2018) |