Located 80 kilometres south of Sicily, the Maltese Islands lie in the Central Mediterranean, with Tunisia to the west and Libya to the south. Although comprising over 20 islands, Malta's total land area is a mere 316 square kilometres and only the three largest islands (Malta, Gozo, and Comino) are inhabited by a total population of 519,562 in 2021. Malta's strategic location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea at the eastern end of the Strait of Sicily has given it great strategic importance as a naval base, trading centre, and way-station for ships heading to India via the Suez Canal after 1869. The Maltese Islands were first settled in 5,900 BC and have been fought over and ruled by a succession of foreign powers: Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Aragonese, the Order of St John, the French, and the British. On 21 September 1964, Malta gained its independence from British rule, voting to become a republic on 13 December 1974, and joining the European Union on 1 May 2004.

Today, Malta is a popular tourist destination, capitalising on its rich history over the millennia, its sun-splashed beaches and quaint villages, and its impressive architecture, from ancient monolithic structures and walled cities to ornate Baroque churches and 19th century British military fortifications. So much on Malta is the legacy of the Order of the Knight Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, also known as the Order of St John, a religious order comprising noblemen from Europe's most important families. After being evicted from Rhodes by the Turks in 1522, the Order was given possession of Malta by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily, in 1530. Making Malta its home base, the devoutly religious Order used its vast wealth to transform the Maltese Islands, erecting impressive fortifications and Catholic churches. After repelling a final Turkish siege in 1565, the Order of St John began construction of its brand new fortified capital city of Valletta in 1566. The city, surrounded by thick walls and bastions, sits perched on a peninsula jutting into Malta's Grand Harbour and features numerous Baroque public, religious, and military buildings to which today's tourists flock. Despite the Order of St John's 268-year rule of Malta ending in 1798 with its surrender to the French Revolutionary forces of Napoleon, the Order and its knights serve as a popular attraction for visitors, with numerous museums and cultural sites telling the story of the Order and its influence on the development of the Maltese Islands.

Malta's maritime history is as fascinating as its architecture and visitors can see relics from a Phoenician trading ship that sank offshore in the 7th century BC and learn about how the Order of St John based its fleet of galleys in the Grand Harbour and sallied forth to intercept Turkish vessels carrying valuable commodities. Later still, under British rule, the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet was headquartered in Valletta, with battleships, battlecruisers, cruisers, and smaller warships being based in the Grand Harbour's vast anchorage and thousands of Maltese men employed in the harbour's extensive dockyards and ship repair facilities. While in the First World War Maltese military hospitals cared for wounded Allied forces evacuated from the Gallipoli campaign, earning Malta the nickname 'Nurse of the Mediterranean', during the Second World War, Malta suffered terribly from Axis attempts to force the British to surrender. These efforts included Axis naval vessels sinking merchant ships bringing critical food, medicines, fuel, and military equipment to Malta and, most notoriously, an incessant campaign of aerial bombing that caused massive destruction and brought those on Malta close to starvation. On 10 July 1943, Malta was the principal jumping-off point for the Allied invasion of Sicily, the largest amphibious assault ever mounted until the Normandy landings in June 1944. Malta's experience (and proud triumph) during the Second World War is another aspect that today is the subject of several museums and historic sites.

The tour below covers only a handful of locations in Malta and any history enthusiast must surely make more than one visit to this tiny, yet fascinating, country.

Photos taken 21-27 October 2023

|

| Malta International Airport, as seen from a Lufthansa flight on Runway 31. The passenger terminal, opened in 1992, has no jet bridges; instead passengers are transported to and from aircraft using shuttle buses. |

|

| An Air Malta Airbus A320neo, registration 9H-NEO, parked on the tarmac at Malta International Airport on the afternoon of 21 October 2023. 9H-NEO was delivered to Air Malta on 4 June 2018. |

|

| Passengers disembark from Lufthansa flight LH 1310, an Airbus A321neo (registration D-AIEM, named Hamm), just before 5pm on 21 October 2023. The flight from Frankfurt takes approximately 2.5 hours. After deplaning, passengers board one of the airport's shuttle buses for the short drive to the terminal. |

|

| The Waterfront Hotel located along the Strand on Triq Ix-Katt in the Sliema neighbourhood across Marsamxett Harbour from Valletta. The hotel opened in 2000 and has 165 rooms, a spa, restaurant, lobby bar, and a rooftop terrace featuring a grill restaurant. |

|

| The lobby of the Waterfront Hotel. |

|

| The entrance to room 919. |

|

| The Waterfront Hotel's electronic room key card. |

|

| Room 919 is a Standard Double with a balcony looking into the hotel's interior courtyard. |

|

| The spacious room features contemporary decor, air-conditioning, ample closet and storage space, a safe for valuables, and a mini-fridge. |

|

| The en suite bathroom in Room 919. A large, walk-in shower stall is on the left (not pictured). |

|

| The balcony of Room 919, looking into the hotel's interior courtyard. A sensor in the sliding door deactivates the room's air conditioner when opened. |

|

| Looking down into the hotel's interior courtyard from Room 919's balcony. The whitewashed walls and potted palms provide a Mediterranean look. |

|

| A hearty breakfast of scrambled eggs with HP Sauce, sausages, hashbrowns, grilled tomatoes, rustic Maltese bread, fruit salad, a peach, mini chocolate croissants, and glasses of apple juice in the hotel's Regatta Restaurant. An enormous breakfast both prepares one for a busy day of sightseeing and avoids the need to stop for lunch, thereby providing one more time at museums and attractions. |

|

| The heated indoor pool on the 10th floor of the Waterfront Hotel. The hotel's spa is adjacent to the pool, and the 10th floor also provides walkout access to the rooftop terrace. |

|

| The Waterfront Hotel's rooftop terrace on the 10th floor. The terrace overlooks the Sliema waterfront and Sliema Creek. The hotel's 1Olive Grill restaurant and bar is located on the terrace. |

|

| Another view of the rooftop terrace, showing the balconies of rooms facing out into the hotel's interior courtyard. |

|

| The rooftop terrace, with an olive tree planted in a raised, tiled planter in the centre. A pleasant place to nap in the Mediterranean warmth, enjoy a good book, or watch the hustle and bustle of Sliema and Sliema Creek below. |

|

| Looking down on Sliema Creek from the rooftop terrace. Manoel Island is across the creek, and immediately below is the large cross-shaped pool of the Aqualuna Beach Club. This waterside lido was built by the Waterfront Hotel, ST Hotels, and 115 the Strand Hotel and features a bistro with poolside service, a bar, sunbeds and gazebos for rent, showers and toilets, and free wifi. The harbourside promenade is popular with walkers and joggers. |

Sliema

|

| The Strand in Sliema, as seen from Triq Ix-Katt, the multi-lane roadway running along the northern edge of Marsamxett Harbour. This densely-populated town is home to many hotels, restaurants, bars, shops, and shopping centres, as well as residential buildings. Behind the busy commercial strip along the Strand, the narrow streets are home to quiet residential neighbourhoods. The Strand's wide harbourside promenade provides pleasant views of Marsamxett Harbour and Sliema Creek, as well as Manoel Island and the historic city of Valletta. Numerous sightseeing cruises depart from the Sliema waterfront, and visitors can also take the short Sliema-Valletta ferry across the harbour. |

|

| The Parish Church of Jesus of Nazareth on Triq Ix-Katt in Sliema. Built by Marquis Ermolao Zimmermann Barbaro di San Giorgio and consecrated in 1895, this church was entrusted to the Dominican Friars in 1908 and was designated a parish church in 1973. It is one of Sliema's four parish churches, housing statues of the prophets and featuring sculptures on its ornade façade. |

|

| Numerous vessels are moored along the Sliema waterfront, including the colourful and historic Stella Maris VIII, seen here. Stella Maris VIII is a sightseeing vessel measuring 17 metres (55.8 feet) in length and 5 metres (16.4 feet) in beam. Over 90 years old, it once transported food and other goods across the Gozo Channel separating the big island of Malta from its smaller sister Gozo. |

|

| Another charter sightseeing vessel along the Sliema waterfront, 22 October 2023. |

|

| The skyline of historic Valletta, dominated by the large dome of the Basilica of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, seen from across Marsamxett Harbour. In the foreground is the swimming pool of the Movida Beach Lido. |

|

| Looking west, up Marsamxett Harbour, with Sliema Creek separating Sliema (right) and Manoel Island (left). |

|

| The Valletta skyline as seen along the harbourside boardwalk near Tigné Point at the eastern end of Marsamxett Harbour. To the right of the dome of the Basilica of Our Lady of Mount Carmel is the spire of the Anglican St Paul's Cathedral. |

|

| Part of the 21st century redevelopment of the Tigné Point foreshore is this pathway through landscaped gardens featuring many native Mediterranean plants. |

|

| Waves lap against the rocky Tigné Point foreshore near the entrance to Marsamxett Harbour. The limestone walls and buildings of Valletta take on a golden hue in the morning sun. |

|

| Located at the tip of Tigné Point is Fort Tigné, with its circular keep feauturing two rows of musketry loopholes and the main gate. The fort was built by the Order of St John between 1793 and 1795 to protect the entrance to Marsamxett Harbour and was named after Francois René Jacob de Tigné, a Knight of the Order of St John, in recognition for his many years of service to the Order. Commissioned by the Order's Grand Master, Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, Fort Tigné was built to a design by Antoine Étienne de Tousard, the Order's chief engineer, and was the last major fortification constructed by the Order before it surrendered to French forces in 1798. The fort was small by 18th century standards, being closer in size to a large redoubt than a fort, but its polygonal design was revolutionary. During the French invasion of 1798, Fort Tigné was armed with 28 guns (of which 15 were serviceable) and 12 mortars and was one of the few fortifications to actively resist the invasion; its garrison successfully repelled a French attempt to capture Fort Tigné on 10 June and it prevented French warships from entering Marsamxett Harbour. However, after being bombarded by French forces on 11-12 June, and given the fall of Valletta and surrounding communities to French forces, the garrison surrendered and Fort Tigné was under French control by 13 June. Fort Tigné came under British control in September 1800 following Britain's expulsion of the French occupiers, with a permanent garrison established in 1805. Damage from the French bombardment in 1798 was repaired and the British installed 30 guns in Fort Tigné by 1815. As part of renovations made by the British, the parapet on the keep was replaced with a traversing platform for a single gun mount. By 1864, the fort had eighteen 32-pounder guns, four 10-inch guns, and an additional 32-pounder gun on the keep. More significant remodelling of Fort Tigné was completed in the last three decades of the 19th century to accommodate new types of guns and provide housing for the garrison. Fort Tigné was damaged by air attacks during the Second World War but continued to serve as a military installation until British forces withdrew from Malta in 1979. In subsequent years, the fort fell into disrepair, with parts of it being vandalised; however, in 2008, Fort Tigné was restored as part of the massive redevelopment of Tigné Point. Fort Tigné is included in Malta's tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage sites as part of the network of fortifications constructed around Malta's harbours by the Order of St John. The site on which Fort Tigné stands played an important role during the Great Siege of Malta in 1565, when the invading Ottoman forces established an artillery battery here to bombard Fort Saint Elmo across the harbour in Valletta. |

|

A final panoramic view of Valletta from the Tigné Point foreshore on 22 October 2023.

|

Three Cities Harbour Cruise

|

| Departing Sliema at 10:30 aboard a sightseeing boat for the 90-minute Three Cities harbour cruise. After cruising up Marsamxett Harbour and along the northern shore of Valletta, the boat briefly enters the Mediterranean to round the point of Valletta and enter the Grand Harbour. In the Grand Harbour, the voyage takes passengers past the Three Cities (Vittoriosa, Senglea and Cospicua) located on the southern edge of the harbour. |

|

| Some of the hundreds of sailboats and yachts moored in the creeks of Marsamxett Harbour. These vessels are at a marina in Lazzarreto Creek in the Ta' Xbiex neighbourhood, across from Manoel Island. |

|

| Larger vessels moored at the Manoel Island Yacht Marina in Lazzaretto Creek. The marina has berths for 350 vessels and can accommodate vessels up to 80 metres (262 feet) in length. |

|

| Vessels of the Maritime Squadron of the Armed Forces of Malta, moored at their base at Hay Wharf in the town of Floriana. The Maritime Squadron is responsible for the security of Maltese territorial waters, including maritime surveillance, law enforcement, and search and rescue duties. Seen here are the four Austal Class vessels P21, P213, and P24 (in the water) and P22 (on blocks ashore). The Austal Class vessels were built by Austal in Perth, Australia and delivered in 2009-10; they are principally used for search and rescue and border patrol duties. The larger vessels on the right are the Emer Class offshore patrol vessel P62 (left) and the Diciotti Class offshore patrol vessel P61 (right). |

|

| The largest vessel of the Maritime Squadron of the Armed Forces of Malta is the OPV748 Class offshore patrol vessel P71, seen here at the squadron's base at Hay Wharf on 22 October 2023. Ordered in October 2018 and launched in February 2021, P71 was commissioned on 22 March 2023. P71 was built by Cantiere Navale Vittoria in Adria, Italy and, upon commissioning, it replaced P61 as the flagship of the Maritime Squadron. The ship measures 78.4 metres (257.2 feet) in length, with a beam of 13 metres (42.6 feet) and a displacement of 2,244 tons at full load. P71's two Wärtsilä diesel engines provide a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h) and a range of 2,100 km at 16 knots (30 km/h). With a crew of four officers and 21 ratings, the ship has accommodations for an additional 20 members of the Special Operations Unit. P71 is equipped with two 9.1 metre (30 foot) rigid-hull inflatable boats and armed with 1 OTO Melara 25mm Oerlikon remote controlled autocannon, one 12.7mm machine gun, and two 7.62mm machine guns. The ship's rear helicopter deck can land seven-ton helicopters such as the Leonardo AW139s operated by the Air Wing of the Armed Forces of Malta. |

|

| A view of Fort Manoel, a star fort on Manoel Island in Marsamxett Harbour. Built by the Order of Saint John in the 18th century, during the reign of the Order's Portuguese Grand Master, António Manoel de Vilhena, Fort Manoel was designed in the Baroque architectural style; as such, it was constructed with a view to both function and aesthetics. After a number of proposals for a fort on this site were presented from 1569 onward, the final design was agreed only in 1723 and the first stone laid on 14 September of that year by Grand Master Vilhena, who financed the construction and established a fund to pay for the costs of maintaining and garrisoning the fort. Construction proceeded rapidly and, by 1734, the fort was an active military establishment. Additional outworks were completed over the course of succeeding years until the entire fort was considered complete in 1761. Fort Manoel was captured by Napoleon's forces during the French invasion of Malta in June 1798, with the British occupying the fort in 1800 after ousting the French. Although the fort's cannons were decommissioned and removed in 1906, a battery of 3.7-inch heavy anti-aircraft guns was installed in and around Fort Manoel during the Second World War, with the fort suffering extensive damage from Axis aerial bombing. British forces utilised Fort Manoel until the garrison was withdrawn in 1964, after which the fort fell into a state of disrepair, exacerbated by acts of vandalism. Restoration work on Fort Manoel commenced in August 2001 and the fort is included in Malta's tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites as part of the Knights' Fortifications. |

|

| Passing a sailboat while heading out of Marsamxett Harbour into the choppy Mediterranean in order to round the tip of Valletta and enter the Grand Harbour. The dome of the Basilica of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and the spire of St Paul's Cathedral are prominent landmarks on Valletta's skyline. |

| |

|

| The St Elmo breakwater protecting the entrance to the Grand Harbour passes to starboard as the tour vessel sails around the tip of Valletta. |

|

| Part of the ramparts built to provide seaward protection for Valletta. On the right stands the Siege Bell Memorial commemorating those who fought and died defending Malta during the Second World War. On the left is Lower Barrakka Gardens. |

|

| In Vittoriosa (originally called Birgu) across Grand Harbour from Valletta, stands Fort St Angelo. Built by the Order of St John in the mid-1500s on the site of a medieval castle, Fort St Angelo was the headquarters of the Order of Saint John during the Ottomans' 1565 Great Siege of Malta. The fort was rebuilt into its current appearance in the 1690s. |

|

| A view of the north side of Fort St Angelo, as seen from Kalkara Creek. |

|

| A view of the south side of Fort St Angelo, as seen from Galleys' Creek. |

|

| Senglea, also known as Città Invicta, one of three cities on the eastern side of Grand Harbour along with Conspicua and Vittoriosa. Built on a narrow finger of land, as with the other two cities, Senglea is home to about 2,700 residents as of 2019. It is named after its founder, Grand Master Claude de la Sengle of the Order of Saint John. |

|

| Giant cranes tower over the modern shipyard in Grand Harbour, at which large cargo and passenger vessels are repaired and overhauled. Seen here on 22 October 2023 is the ferry GNV Sealand and, in the dry dock next to it, the 43,025 gross ton Liberian-flagged bulk carrier Karpaty. |

|

| The GNV Sealand was completed by Italy's Visentini Shipyard in 2009 and originally named Scottish Viking. Now operated by Grandi Navi Veloci, GNV Sealand sails between Valencia, Palma de Mallorca, and Ibiza in Spain. The 26,904 gross ton ferry is 186 metres (610.2 feet) in length, with a beam of 25.6 metres (84 feet), and a draught of 6.85 metres (22.5 feet). She can carry 830 passengers and 200 cars at a top speed of 21.5 knots (40 km/h). |

|

| A view down Grand Harbour, with Senglea on the right and Fort St Angelo and Vittoriosa on the left. |

|

| The MV Jean De La Valette, a high-speed aluminum catamaran ferry operated by Malta-based Virtu Ferries, moored at the ferry terminal in Grand Harbour. The 850-ton ferry was built by Australia's Austal in 2010 and was the largest high-speed catamaran in the Mediterranean when it entered service. In October 2023, MV Jean De La Valette operated between Valletta and Augusta and/or Catania in Sicily, carrying up to 800 passengers, 24 crew, and 156 cars or 45 cars and 342 truck lane metres; vehicles can be loaded and unloaded via ramps at the stern and port side. The vessel is 106.5 metres (349 feet) in length, with a beam of 23.8 metres (78 feet) and a draught of 4.9 metres (16 feet). Four waterjets, powered by four diesel engines, drive the Jean De La Valette at a speed of 38 knots (70.4 km/h). MV Jean De La Valette features six air-conditioned lounges with leather reclining seats, open air seating decks, a shop, and three food service outlets. |

|

| Looking down Grand Harbour, with Valletta on the left. |

|

| Luxury yachts moored in French Creek on the south side of Senglea. As the home port of a large number of luxury yachts and a popular destination for foreign yachts, Grand Harbour has developed a significant yacht maintenance industry. |

|

| The motor yacht Paloma, built by Ishikawajima-Harima in Japan in 1965. The 617 gross ton vessel measures 60.25 metres (197.67 feet) in length, with a beam of 8.85 metres (29.03 feet). Paloma is powered by two 1,000-horsepower Caterpillar diesel engines, producing a maximum speed of 17 knots (31.5 km/h) and a cruising speed of 15 knots (27.8 km/h) and giving the vessel a range of 4,000 nautical miles (7,408 kilometres). With seven cabins, Paloma can accommodate up to 14 guests and carries a crew of 16. |

|

| Moored in Valletta is the four-masted barquentine Star Flyer, built by Belgium's Scheepswerven van Langerbrugge in 1990-91 and operated by Swedish-based luxury cruise line Star Clippers Ltd. The 2,298 gross ton, Maltese-flagged cruise ship measures 111.57 metres (366.04 feet) in length, with a beam of 15.14 metres (49.67 feet), and a draught of 5.50 metres (18.04 feet). Star Flyer carries 170 passengers and is powered by 16 sails and a single Caterpillar diesel engine. |

|

| The high ramparts of the fortifications of Valletta, with Upper Barrakka Gardens and the Saluting Battery seen at the centre top. To the left, the tall column is the Barrakka Lift, built in 2012 to help people more easily move from the harbour to the heights of Valletta. Sitting at the water's edge (to the right of the black barge) is the Malta Custom House, built in 1774-76 to a design by Maltese architect Giuseppe Bonnici (1707-1779), and one of the few government buildings still serving in its original role. The Custom House was officially opened by the Order of St John's Grand Master, Fra Emmanuel Marie des Neiges de Rohan-Polduc, on 27 July 1776; Grand Master De Rohan personally funded the construction of the Custom House, whose walls measure up to 3.66 metres (12 feet) in thickness in some places. The building's walls were built of coralline limestone up to the second storey in order to resist the damaging effects of salty ocean spray, with normal globigerina limestone used on the upper storeys of the building. The Custom House's façade overlooking Grand Harbour reportedly featured a stone depiction of the coat-of-arms of Grand Master De Rohan, along with the figures of two mermaids on each side supporting a large frieze above; however, it is believed that the coat-of-arms was destroyed by French troops during the occupation of 1798, with the mermaids and frieze being worn away over time by strong northeast winds. |

|

| A line of luxury yachts moored under the ramparts of Fort Saint Angelo in Senglea. From left to right are: Lady Maja I (62 metres, built 2005); Illusion I (55.5 metres, built 1983); Seagull II (54 metres, built 1952); and Starlust (68.2 metres, built 2020). Malta is the third most popular flag state for superyachts, with over 1,000 superyachts registered under the Maltese flag. |

|

| Looking across Galleys' Creek towards the densely-populated city of Senglea. |

|

| Small boats moored in Galleys' Creek between Vittoriosa and Senglea, with Senglea's old limestone residential buildings seen in the background, featuring colourful Maltese-style enclosed balconies. The bell towers and dome of the Basilica of the Nativity of Mary, also known as the Basilica of Our Lady of Victories, can be seen on the left. |

|

| Returning to the dock in Sliema after the 90-minute Three Cities Harbour Cruise. |

National War Museum and Fort St Elmo

|

| A seaward view of Fort St Elmo, as seen from outside the Grand Harbour. Fort St Elmo was important to the defence of the entrances to Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour. the fort was built in the shape of a star to a design by military engineer Pietro Pardo in the mid-16th century and played a critical role during the Great Siege of 1565. For 30 days, Fort St Elmo resisted the attacking Ottoman forces before finally being captured. It was rebuilt after the siege and continued to expand over time in response to military needs. Today, Fort St Elmo houses the National War Museum. |

|

| Located outside the landward walls of Fort St Elmo are underground grain silos (fossos) built by the Order of St John to store grain in the event of a siege. The bell-shaped fossos were filled with wheat and then carefully sealed with large stone caps (some circular and some squarish) and mortar in order to ensure a dry environment for the contents. Stone slabs form the pavement between the capstones. Built during the reign of Grand Master Gregorio Caraffa (1680-1690) when trade and commerce were increasing due to infrastructure improvements, the fossos were managed by the Universita’ dei Grani. Although 70 fossos were originally constructed in this area, only 30 still survive, while 75 similar underground granaries were built by the British in the Valletta suburb of Floriana in the 19th century. Grain stored in Valletta's fossos fed French occupying troops during the British blockade between 1798 and 1800 and delayed their eventual surrender. |

|

| The ticket office and gift shop for Fort St Elmo and the National War Museum is located in a former gunpowder magazine, also known as a polverista. The word 'polverista' is derived from the Italian 'polvere da sparo' (gunpowder). This building was constructed by the order of St John in the 1600s to store gunpowder for the cannon on St Lazarus Bastion, located on the curtain wall. British forces continued to use the magazine after 1800 but eventually converted it to an office for the Royal Engineers in the early 1900s and, following the Second World War, to a guardroom. |

|

| Proceeding from the entrance, visitors pass the St Lazarus Bastion. St Lazarus Bastion is technically located outside of Fort St Elmo due to its having been built as part of the Valletta enciente (the enclosure of a fortified place) constructed in the 16th century. In 1785, the St Lazarus Bastion was armed with seven cannons and 11 mortars and in 1885 was equipped with a 38-ton gun. This gun was replaced by a single 6-inch breech-loading gun between 1903 and 1936. |

|

| St Lazarus Battery was built in 1908 and was armed with two quick-firing 12-pounder guns in 1910. Quick-firing guns offered a higher rate of fire than older cannons and also used smokeless cordite propellant, which protected the guns against being spotted by the enemy. These quick-firing guns were later removed from the battery and replaced by a twin 6-pounder quick firing gun in 1938. The twin 6-pounder was employed in a defensive role during the Second World War. |

|

| Two large ship's anchors on display along the path leading visitors toward Fort St Elmo. |

|

| The Victorian era gate into Fort St Elmo. Although most of the ramparts of Valletta were demilitarised by the end of the 1800s, the Carafa Enciente enclosing Fort St Elmo retained its guns for coast defence purposes. This gate was therefore built in 1880 to separate the civilian and military zones. |

|

| The Orderly Room, built by the British Army around 1910 and used for the administration of the fort. Prior to the Second World War, it was used as offices for the fort's artillery batteries. It was from here that daily duties were distributed to the fort's garrison. In the 1960s the building served as an education centre. |

|

| Abercrombie's Casemates. Previously a curtain wall, around 1860 the Abercrombie curtain was renovated into a casemated (roofed) battery mounting guns overlooking the entrance to Grand Harbour. In 1864, Abercrombie's Casemates was equipped with sixteen 68-pounder guns and by 1885 it was armed with eight 80-pounder guns. During the decade between 1897 and 1907, Abercrombie's Casemates featured four 12-pounder quick-firing guns and two machine guns. Unlike previous artillery pieces, these quick-firing guns combined propellant and projectile in a single cartridge for easier handling and a higher rate of fire. The ammunition for the quick-firing guns was stored in underground magazines and hoisted to the guns by means of lifts. |

|

| A view of Abercrombie's Casemates from atop Fort St Elmo. Considered obsolete by the early 1900s, some of the casemates were demolished while others were converted into offices and storehouses. |

|

| A memorial to HMS Urge, a British U-class submarine lost with all hands after hitting a German mine off Malta on 27 April 1942. Before its loss, HMS Urge had a successful war record, sinking Axis warships and supply vessels, landing and recovering British special forces and Allied secret agents on enemy coasts, and helping to defend the vital supply convoys to Malta. HMS Urge departed Malta for Alexandria shortly before dawn on 27 April 1942 and was never heard from again. The ship's company of 32 officers and men, as well as 12 passengers, were lost and the wreck was not located until 2019. |

|

| A view of the St Elmo breakwater protecting the entrance to Grand Harbour. A much shorter breakwater, the Ricasoli East breakwater, extends from the other side of the harbour entrance. |

|

| A block of storehouses constructed around 1880 and originally incorporating several machinery and gun sheds. Plans of Fort St Elmo from before the Second World War show this block containing a garage for a fire engine. The arched casemates were also used as ammunition magazines for guns located nearby, as well as a shelter for the gun crews. |

|

| A collection of heavy, Rifled Muzzle Loading guns from the latter half of the 19th century. As artillery became larger and heavier through the 1800s, new military architecture was required to accommodate them. The Carafa Enceinte around Fort St Elmo was modified through the addition of new gun emplacements and the reinforcement of existing gun batteries with concrete in the 1870s. When breech-loading guns were introduced in the early 20th century, a further round of architectural modifications was required. |

|

| A plaque marking the grave of General Sir Ralph Abercromby (1734-1801), the commander of the British Army's troops in the Mediterranean. Abercromby participated in the British blockade of French forces occupying Malta in 1798-1800 and in 1801 was sent to recapture Egypt from the French. Shot and killed in battle in Egypt, Abercromby's body was transported to Malta and interred within this bastion, which was renamed after him. As noted on the upper plaque, Abercromby's remains were moved to a vault under the bastion in 1871. |

|

| Descending a ramp to the underground magazines of Abercrombie's Bastion. |

|

| One of two concrete control towers atop Abercrombie's Bastion, built in 1938 to control the fire of the two twin 6-pounder quick-firing guns installed here. It was here on 26 July 1941 that soldiers of the Royal Malta Artillery (RMA) manning the guns were able to disrupt a seaborne attack by nine Italian explosive motor boats from the Italian Navy's 10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla (Decima Flottiglia MAS) against merchant ships forming part of the 'Substance' convoy anchored in the Grand Harbour. This failed attack was the only one of its kind mounted against Malta during the Second World War. |

|

| One of two gun emplacements in Abercrombie's Bastion, located at the tip of the Sciberras Peninsula on which Valletta and Fort St Elmo are located. While a twin 6-pounder quick-firing gun was mounted on the circular platform on the right, the guns were removed in the post-war period as part of the fort's decommissioning. |

|

| The Carafa Enceinte fronting Abercrombie's Bastion. The antennae and aerials on the upper left sit atop the Harbour Fire Command complex looking out over the approaches to Grand Harbour from the fort's cavalier. |

|

| A look at two of the concrete towers built in 1938 as part of Fort St Elmo's coastal defences. These towers were used to spot enemy ships and aircraft and to direct the fire of each tower's associated twin 6-pounder guns. |

|

| Abercrombie's Bastion on the left was originally named St John's Bastion when constructed as a section of the Carafa Enceinte enclosing Fort St Elmo as part of the Valletta fortifications. The Carafa Enceinte was built at the direction of Grand Master Gregorio Carafa in 1687 in order to deny an occupying enemy the use of the foreshore below Fort St Elmo. This bastioned enceinte was designed by the Dutch military engineer Carlos Grunenbergh and included three bastions: St John's Bastion (renamed Abercrombie's Bastion), Immaculate Conception Bastion (renamed Ball's Bastion), and St Gregory's Bastion. During the period of British occupation of Malta after 1800, the Carafa Enceinte was considered part of Fort St Elmo itself. |

|

| The Porta del Soccorso was originally believed to be the relief gate through which casualties were evacuated from the fort and new supplies and reinforcements brought in from Birgu during the Great Siege of 1565. It has since been confirmed that this was Fort St Elmo's original main gate until a new one was constructed by 1570. Although Fort St Elmo proper begins beyond this gate, the British Army considered the surrounding enceinte as part of the fort. The eye mounted above the Porta del Soccorso (the l-għajn) symbolises watch duties, while the coats of arms of Grand Masters d'Homedes, de Valette, and Carafa are also mounted above the gate. To the left of the gate is a modern bronze sculptural depiction of knights of the Order of St John. |

|

| The entrance to St Anne's Chapel, just inside the fort after passing through the Porta del Soccorso. |

|

| The interior of St Anne's Chapel, featuring a high coffered ceiling. The chapel, originally dedicated to Saint Elmo, already existed in 1488 and was incorporated within Fort St Elmo, constructed in 1552. It was re-dedicated to St Anne, the patron saint of the Order of St John's navy. St Anne's Chapel housed an icon of Saint Anne, brought to Malta by the Knights of St John in 1530 and now housed at the Malta Maritime Museum. The final defence of Fort St Elmo during the Great Siege of 1565 was fought here, with the handful of remaining knights being slain by Ottoman forces who captured the fort on 23 June after 30 days of resistance. The coffered ceiling and the altar were added to the chapel in the 1600s. |

|

| The Piazza d'Armi, a large parade ground flanked on three sides by soldiers' barracks designed by French military engineer Charles de Mondion and constructed between 1727 and 1729. These were the first modern barracks blocks built by the Order of St John in Malta and were specifically designed to provide improved sanitation and hygiene, as well as impose more discipline and control over the soldiers residing in them. The barracks housed 200 soldiers of the Grand Master's Guard. |

|

| The lower tier of one of the casemated barracks blocks now houses various displays, including a recreation of a Second World War soldier's accommodation, seen here. |

|

| This display by the re-enactment group Scuola d'Armi (Show of Arms) showcases medieval weaponry, including swords, rapiers, and early firearms such as the musket and the 'handgonne'. The re-enactors of Scuola d'Armi train in the use of these medieval weapons using original combat manuals and under the guidance of foreign qualified experts. |

|

| The members of Scuola d'Armi also practice period crafting skills, such as the making of ink and quills, leather-working, cookery, medical practice, carpentry, fletching (the addition of stabilising structures to arrows), sewing, and weaving, some of which are depicted in this display. |

|

| A display by Legio X Fretensis, a re-enactment group focused on the Roman period. The group portrays living history as Roman legionaries serving in the 5th Cohort of the 10th Legion Fretensis, as well as citizens of Roman society in the first century AD. |

|

| A display of weapons, armour, and equipment by the Legio X Fretensis re-enactment group. The 10th Legion Fretensis was formed by Gaius Octavius and given the number '10' in honour of Julius Caesar's famous 10th Legion. The 10th Legion Fretensis fought during the period of civil war that led to the dissolution of the Roman Republic and Octavian's victory resulted in him being hailed Emperor by his troops. The legion's role in the Battle of Naulochus, near the Strait of Messina ('Fretum Siculum' in Latin), earned it its nickname Fretensis. The 10th Legion Fretensis is recorded to have existed until at least the fifth century AD. The legion's campaigns took it to the East, where it fought in the First Jewish War (66-73 AD) under the supreme command of Vespasian, and the Second Jewish War (132-136 AD) under Emperor Hadrian. |

|

| On the east side of the Piazza d'Armi stands the Church of St Anne, built in 1729 during the reign of Grand Master Antonio Manoel de Vilhena. This garrison church was constructed to enhance the soldiers' devotion to St Anne and was part of the parade ground's redesign. |

|

| The Church of St Anne reflects the grand, ornamental, and dramatic styling of 18th century baroque architecture. The church housed an icon of St Anne holding Our Lady, which was brought to Malta following the Order of St John's expulsion from Rhodes by the Ottomans in 1530. |

|

| The National War Museum's exhibits are displayed in chronological order from ancient to modern times in a series of buildings housed within Fort St Elmo. The earliest artefacts are housed in the former Non-Commissioned Officers' Mess built in the 18th century and used by the British Army during the 19th and 20th centuries. Seen here are displays on prehistoric Malta, specifically the Bronze Age (c. 2,400-700 BC). The Bronze Age saw settlers to the Maltese Islands bring copper axes, chisels, daggers, and awls. The period is also characterised by easily defended hilltop settlements and defensive structures designed to withstand a siege. |

|

| A collection of chert and flint blades, probably used for domestic purposes. These items, dating from c. 3,600-2,500 BC, were found at the Ħal Ġinwi Temple in Żejtun, Malta and at the Xagħra Stone Circle on the Maltese island of Gozo. |

|

| Punic ceramic vessels used for the transport and storage of various products. The provenance of these vessels is unknown, but they are believed to date from between the 8th and 3rd centuries BC. |

|

| Roman-Byzantine column-topping capitals, likely from a religious or important civic building. The provenance of these artefacts is unknown, though they date from between the 1st and 9th centuries AD. |

|

| A tombstone with Arabic inscription recording the burial of local Muslims, dating from between the 9th and 11th centuries AD. |

|

| The National War Museum's Building 2 is a former barracks built in the 1700s and used by both the Order of St John and, later, the British Army to house some of the fort's garrison. This particular building was reconfigured as a recreational facility in 1910, with a billiard table and a library. In the 1960s, it was also used as Headquarters' offices. |

|

| Inside Building 2 is housed displays on Malta's military history in the 1500s, including the Great Siege of Malta of 1565. As a scene setter, this display notes how the Mediterranean had become a battleground between the Ottoman empire and Christian Europe in the 16th century. Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, after which Ottoman forces made steady inroads into Christian lands and, by 1523, had captured the entire eastern Mediterranean, Egypt, and the Balkans, and evicted the Knights of St John from their island fortress of Rhodes. |

|

| Glass cases hold a replica of a typical shield used by the Knights of the Order of St John, as well as an example of the body armour worn by a knight. In 1530, following their ouster from Rhodes, the Knights of St John were given Malta and the North African port of Tripoli by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Charles V wished to prevent the expansion of Ottoman influence into the western Mediterranean by re-establishing the Order of St John on the strategically important Maltese Islands. The Order's Grand Master, Philippe de Villiers de L'Isle-Adam accepted the key to the Maltese city of Mdina and sent letters across Europe summoning the dispersed knights to join him on the islands. The Order established its base at Birgu, now Vittoriosa, and set about reinforcing and remodelling Fort St Angelo as its new headquarters. Additionally, the knights upgraded the existing medieval galley arsenal and, in 1532, they began building an infirmary, an armoury, and hostels (auberges) for the different nationalities of the knights. During their early years on Malta, the Knights of St John launched raids against the Turks and grew their wealth. In 1551, the notorious Turkish corsair Dragut raided the Maltese island of Gozo, carrying off 6,000 residents as slaves. In response, the knights reorganised and rearmed their forces and built two new forts, St Michael and St Elmo, to defend against future Ottoman raids. |

|

|

|

| A reproduction of the banner of the Spanish Order of Santiago, featuring a red cross of Saint James terminating in a sword. The Order of Santiago was founded in 1160, during the Spanish Reconquista (722-1492) to fight against Moorish rule in Spain and protect pilgrims. Knights from the Order of Santiago helped to defend Malta during the Great Siege of 1565. |

|

| One of the displays on the Great Siege of Malta of 1565. Forewarned by spies in 1564, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette recalled knights from across Europe and unsuccessfully petitioned European monarchs for military assistance. When the Ottomans finally invaded on 20 May 1565, Malta was defended by fewer than 9,000 men, including around 8,000 Maltese militia and a mere 600 knights. On 28 May, Ottoman forces commenced their attack on Fort St Elmo. Weeks of constant bombardment and vicious hand-to-hand fighting followed, with the fort's 946 original defenders (including 100 knights) and subsequent reinforcements repelling successive attacks and inflicting between 6,000 and 8,000 casualties on the Ottomans. With the fort battered into rubble and overrun by the Ottomans, the few remaining defenders surrendered on 23 June, having lost 1,200 men killed, including 110 knights. |

|

| A display of Ottoman weapons, armour, and cannonballs. The 40,000-strong Ottoman land force under Mustapha Pasha positioned large cannons on Mount Sciberras (on which the city of Valletta was eventually built) to bombard Fort St Elmo with cannonballs, some weighing up to 170 pounds. In addition to the stout defence of the fort's garrison, Ottoman forces suffered from disease which spread through their camps. After capturing the fort's cavalier, the Ottoman cannons could fire directly into Fort St Elmo, with the defeat of the defenders only a matter of time once the Ottomans had cut off the knights' cross-harbour supply of reinforcements and supplies. Despite the Ottoman victory over Fort St Elmo, a carefully-planned counter-offensive by the knights repelled the invaders and the arrival of reinforcements from Sicily in September forced the Ottomans to evacuate their forces from Malta. Praise, military support, and money to rebuild Malta poured in from the grateful rulers of Christian Europe, while Pope Pius V sent his favourite military architect, Francesco Laparelli, to help ensure that Malta remained the bulwark of Christianity. |

|

| Building 3, dedicated to the rule of Malta by the Knights of the Order of St John during the period between the Great Siege of 1565 and the Order's surrender to Revolutionary France in 1798, followed by the period of British occupation. Building 3 stands on the site of a thick walled rampart (cavalier) in 1760, which was in turn heavily modified by 1830 and then converted into an ablutions (washroom) facility by 1910. |

|

| This section of the exhibit details the golden era of the Order of St John's rule of Malta, when the knights enjoyed widespread praise for defeating the Ottoman invasion, the island's defences were rebuilt and strengthened, and the fortified city of Valletta was built. After the defeat of the Ottomans, Grand Master Hugues Loubenx de Verdalle built defences and began developing Valletta. This effort included the construction of hostels (auberges) for the Langues (the national groups within the Order), as well as churches, hospitals, and public buildings. Grand Master de Verdalle also regulated and taxed the activities of corsairs and merchants. |

|

| Left: A 17th century pharmacy jar (majolica Albarello) of the kind used in the Order of St John's hospitals. Right: an 18th century gilt, leather-bound book used by members of the Order for devotional prayers, saying Mass, and celebrating the Order's martyrs and saints' feast days. |

|

| Glass cases hold a variety of weapons and equipment used by the Knights of the Order of St John, including a 16th century Morion helmet; an early 17th century rapier; metal and brass hilted swords from the late-17th and 18th centuries, respectively; and two 17th century staves. It was Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt (ruled 1601-1622), a talented engineer and strategist, who strengthened Malta's coastal defences and began re-equipping the Order through the creation of a foundry at Valletta. Cannon makers and craftsmen were employed to bolster the Order's arsenal and armoury, while Wignacourt raised funds to build new galleys for the Order's navy. |

|

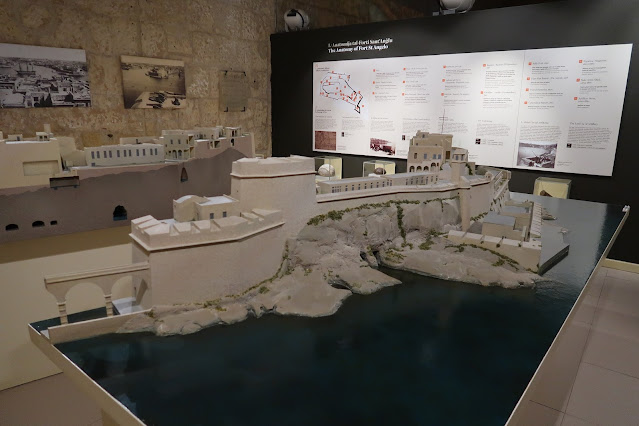

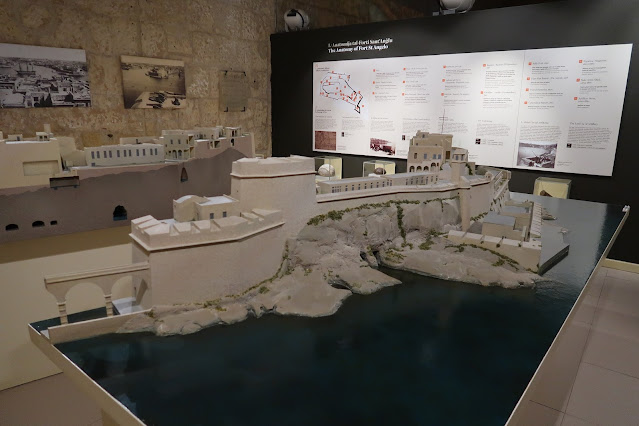

| A scale model of Fort St Angelo in Vittoriosa, the Order of St John's headquarters during the Great Siege of Malta of 1565. |

|

| It was on this table on 5 September 1800 that French and British representatives signed a treaty confirming the capitulation and departure of French forces on Malta following two years of blockade by the Royal Navy. When the Order of St John surrendered to Napoleon on 12 June 1798, the era of the Order's rule of Malta came to an end. The French occupation brought modernity to Malta, with the French establishing the island's first republican government, abolishing slavery, instituting a new legal framework and civil code, establishing 12 municipalities, replacing the religious university with a science-based Ecole Centrale, and abolishing the feudal rights of the church and older nobility. However, French looting of Malta's churches and disruption to Malta's traditional economy also aroused great anger among the Maltese people. By 1800, with no chance of reinforcements from France and French forces desperate for supplies, General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois contacted British commander Major-General Henry Pigot and offered to surrender. The treaty of capitulation was signed behind closed doors with no Maltese officials present as Vaubois did not want to surrender to the Maltese. Granted the right to keep their weapons and spoils of war, the French forces were quickly repatriated to Marseilles. |

|

| A gallery devoted to Malta's military history during the period of British rule, with a focus on the period 1814-1913. Malta was declared a Crown Colony in 1815 and soon became Britain's Mediterranean naval base and a well-defended strategic forward base for the British Army. It was from Malta that British forces could manage campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean and beyond. The fortunes of Malta during this period fluctuated with the level of military activity in the region, with new docks being built to service British ships involved in the Crimean War (1854-56) and maritime activity surging again after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Indeed, Malta became a hub for global trade and a staging post for British troops deploying around the Empire. Malta's importance grew with Britain's need to protect the vital Mediterranean passage to India, China, and the Far East. Although the fortunes of the Maltese people waxed and waned with the boom and bust cycle of military expenditures, overall Malta prospered greatly during the period of British rule. The glass case in the centre of the room contains various British pattern swords, infantry rifles, and revolvers, as well as an Austro-Hungarian Gasser M1870 army revolver. Displays around the gallery recount the events occurring in Malta and the wider world during the period between 1814 and 1913. |

|

| A Royal Artillery uniform jacket made in Malta to an official British pattern and dating from the mid- to late-19th century. |

|

| A pair of First World War-era torpedoes displayed outside the National War Museum's Building 4, dedicated to the history of Malta during the two World Wars. |

|

| One of two captured 25cm German schwere Minenwerfer (heavy mine-launchers) brought to Malta by British forces after the First World War as prizes. The schwere Minewerfer had a short, rifled barrel and was muzzle-loaded and highly portable. The first versions of this weapon were introduced in 1910, followed in 1916 by a longer-barrelled version. Schwere Minenwerfers were used extensively in trench warfare and against fortifications in Belgium and northern France during the war. |

|

| A display of helmets from the First World War, including a German M1918 ear cut-out steel helmet (left); a British 'Brodie' steel helmet (middle, bottom); a British pith helmet (middle, top); and a French M1915 Adrian steel helmet (right). |

|

| A display on Malta's role in the First World War as 'Nurse of the Mediterranean'. While Malta had only four hospitals with a combined 268 beds when the war broke out in 1914, 1,000 sick and wounded soldiers were sent to Malta on 29 April 1915 following the landings at Gallipoli in Turkey. Within a month, the number of patients had increased to 4,000 and, when British and ANZAC troops were finally withdrawn from Gallipoli in January 1916, Malta's 28 hospitals and convalescent centres boasted 20,000 beds. A medical staff comprising 334 medical officers, 913 nurses, and 2,032 other support staff from around the world cared for the 2,000 wounded and sick soldiers arriving in Malta every week. Over the course of the war, over 120,000 military patients of all ranks passed through Malta, with a number of those who died in hospital being buried on the island. |

|

| The Gloster Sea Gladiator named 'Faith'. This aircraft, registration N5520, was manufactured by the Gloster Aircraft Company and is the only survivor of three such Sea Gladiators which participated in the defence of Malta during the early days of the Axis attacks in 1940. These three obsolete aircraft flew non-stop missions over 10 days in attempts to break up Italian air attacks on the island, thereby earning them the nicknames Faith, Hope, and Charity. 'Faith' was recovered from a quarry at Kalafrana in southern Malta and subsequently restored and presented to the people of Malta by the Royal Air Force on 3 September 1943. |

|

| A display on Malta's preparations for war in the summer of 1940, noting efforts to secure the island's coastline using a handful of British regiments and the King's Own Malta Regiment. Nevertheless, with Britain facing a potential threat of German invasion, the Maltese were unsure what resources could be sent to them to bolster the defences. When the first Italian bombing raids occurred on 11 June 1940, Malta had few airworthy aircraft, only 34 heavy anti-aircraft guns, eight light anti-aircraft guns, and one radar set on the island. Malta was divided into sectors, each with its own Air Raid Precautions (ARP) organisation, civilians were given war jobs, and supplies were stockpiled. Maltese men enlisted in the British regiments and in the Malta 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battalion, and the Malta Volunteer Force was formed. Given the threat posed to Valletta by Axis air raids, many Maltese people left the city to live in the countryside. |

|

| The uniform of a German Luftwaffe Oberleutnant, equivalent in rank to a Flying Officer in the Royal Air Force. With Italian forces bogged down in North Africa and Italian air attacks against Malta largely ineffective, Nazi Germany sent forces to the Mediterranean to assist the Italian effort. The Luftwaffe's Fliegerkorps X, sent to Sicily in December 1940, was the first unit to operate over Malta. In October 1941, Hitler ordered Luftflotte II to transfer from the Russian front to Italy and in December 1941 Fliegerkorps II arrived in Sicily, under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. Kesselring's orders were to neutralise Malta once and for all. Axis aircraft based in Sicily could reach Malta in just 20 minutes. Although Axis air raids were incessant and caused great damage to Malta, the island's defences shot down or damaged many enemy aircraft. |

|

| A display recounting the build-up of forces on 'Fortress Malta' in the summer of 1941, when Royal Air Force and Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm joint operations began choking off the flow of Axis supplies to North Africa and struck targets in Italy. On Malta, 3,000 soldiers and local civilian conscripts repaired and reinforced airfields and built underground workshops, while convoys fought their way through German and Italian attacks to deliver vital supplies to the beleaguered island. Beaufort torpedo bombers and Hurricane fighters were shipped to Malta and, using intelligence gleaned from coded German wireless signals and reconnaissance patrols, British forces were able to intercept and sink 60% of Axis convoys. |

|

| A painting depicting the three Gloster Sea Gladiators Hope, Faith, and Charity which, in 1940, comprised Malta's entire fighter defence against Italian air attacks. These three aircraft, kept flying by a rotation of pilots, forced the Italian attackers to fly at high altitudes and misled the Italian air force into believing that Malta was more heavily defended than it really was. |

|

| A display on the war in the air in 1941-42, in which Royal Air Force, Fleet Air Arm, and Royal Navy joint operations mounted from Malta successfully disrupted German operations in North Africa through the sinking of Axis supply convoys. Despite these successes, Malta continued to endure heavy air raids against its airfields, which were repaired by army ground crews (due to a shortage of Royal Air Force personnel) who hastily filled in bomb craters, patched up aircraft, and constructed protective pens for those aircraft. In aerial combat, the older Hurricane fighters were no match for faster and more powerful German planes, but new Spitfire Mk V fighters began arriving on Malta in March 1942 to provide air cover for friendly convoys approaching Malta. Displayed in this case is a piece of wreckage bearing a swastika from the tail of a German Junkers JU-87 Stuka shot down near Żonqor in eastern Malta on 3 May 1942; while the pilot was killed, the gunner was captured alive. Other items displayed here include aircraft components salvaged from various German and Italian aircraft shot down on Malta; a double-barrelled flare pistol recovered from a German plane; a metal swastika worn by a German pilot shot down over Malta in 1942; and the badges of various Royal Air Force squadrons based on Malta. |

|

| The uniform of a rating on the British battleship HMS Vanguard. By the time of the Second World War, Malta had been a British naval base for well over a century. When their ships were in port, naval ratings would scrub the decks or undertake training in navigation, boat launching, and judo. During the war, the Royal Navy's vessels were in constant danger of attack, whether anchored in Grand Harbour or out in the Mediterranean. Many Maltese naval ratings served in the Royal Navy during the war on auxiliary minesweepers. |

|

| A display on the war at sea. Despite the Axis air attacks on Malta which caused the British Mediterranean Fleet to relocate to Alexandria, Egypt, the island remained key to British naval power in the region and its shipyard workers continued to provide vital repair services for Allied shipping. British submarines based at Manoel Island in Marsamxett Harbour ventured forth to attack German shipping while also being used to bring in limited supplies of ammunition and medicine; one submarine, HMS Clyde, was even converted into a cargo transport submarine. After a hiatus, the Luftwaffe resumed attacks on Grand Harbour's shipyards and docks and German and Italian naval forces laid minefields near the approaches to Grand Harbour in an attempt to prevent supplies from getting to Malta and bottle up British naval forces in the harbour. Items displayed here include parts salvaged from the British destroyer HMS Maori, sunk in the Grand Harbour in February 1942; badges from various Royal Navy ships and submarines; a life jacket from the American aircraft carrier USS Wasp; the white ensign flag from the minelayer ML 126; items of Royal Navy protective clothing for gun crews; and the wheel from the MV Moor. |

|

| The bell from HMS Maori, a Royal Navy Tribal-class destroyer of the British Mediterranean Fleet. Launched on 2 September 1937, Maori was attacked by German aircraft on 12 February 1942 while in Valletta's Grand Harbour and sank with the loss of one life. The wreck was later raised and scuttled outside the harbour, off Fort St Elmo, on 15 July 1945. |

|

| A display on the 'Illustrious Blitz', the attack by more than 60 Junkers JU-87 and JU-88 aircraft on the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious on 10 January 1941. As part of the escort for the Operation Excess convoy from Gibraltar to Malta, Illustrious was a prime target for the Luftwaffe squadrons based on Sicily. The carrier was hit six times and extensively damaged, with 126 crewmen killed. Through the heroic efforts of her crew, Illustrious limped into Malta's Grand Harbour. On 16 January, German aircraft launched a heavy bombing raid on the docks where Illustrious was under repair, with nearby civilian areas bearing the brunt of the attack. |

|

| A closer look at the replica of the damaged ship's bell from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, bombed by German aircraft on 10 January 1941. This replica bell was presented to the National War Museum Association by Admiral Sir Charles Madden on behalf of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, UK. |

|

| The uniform of a Private of the 8th Ardwick Battalion of the Manchester Regiment. Given the shortage of Royal Air Force ground crews on Malta, the Manchester Regiment became expert in servicing, refuelling, and rearming fighter aircraft for a quick turnaround under constant attacks during the day and night. Soldiers of the regiment also cleared debris from Malta's streets and salvaged bomb-damaged houses and property. |

|

| A British Army M20 motorcycle manufactured by the Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) Ltd. |

|

| The uniform of a Private serving with British forces in North Africa. Axis and Allied troops fought in the harsh conditions of North Africa for almost three years. The British 7th Armoured Division was composed of various tank and Hussar regiments, later augmented by Eighth Army ground troops and Royal Air Force personnel who were deployed across North Africa to protect the vital Suez Canal. Britain's North African campaign was supported by Malta-based aircraft and submarines which intercepted and attacked Axis supply convoys sustaining the German Afrika Korps under Erwin Rommel. |

|

| The Second World War gallery in Building 4. |

|

| A display of Second World War equipment. On the right, painted in desert tan, is a Bofors 40mm light anti-aircraft gun, designed by AB Bofors in 1928 for the Swedish navy and adapted for use as a land weapon. Malta was poorly defended in July 1939 and of the 60 Bofors 40mm guns expected to bolster the island's harbour defences, only eight actually arrived. By early 1941, there were 129 Bofors 40mm guns on Malta but by 1944 the number had declined to 84, covering the Grand Harbour and the airfields. In addition to their anti-aircraft role on Malta, Bofors guns in other theatres were also used to fire horizontal tracer shells to mark safe paths for soldiers through minefields. |

|

| Seen on the right is a captured Italian Cannone da 47/32 M1939 (Breda 47mm gun). Approximately 100 of these captured guns were refurbished at a depot in Alexandria, Egypt and issued to various Allied units for second line service. Some of these were sent to Malta to reinforce the island's defences. |

|

| The damaged propeller from a Junkers JU-87 Stuka dive bomber believed to have been shot down during the 'Illustrious Blitz' raids on the Grand Harbour in January 1941. This propeller was recovered from Galleys' Creek in Senglea. The B-2 variant of the Stuka was fitted with propeller-driven sirens, nicknamed 'Jericho trumpets', whose purpose was to add to the terror of an air raid. |

|

| A 90-centimetre (3-foot) Projector Anti-Aircraft searchlight. This powerful searchlight was powered by a 90-watt Lister generator to create a focused beam of light with two million candlepower that could reach five miles (eight kilometres). Some searchlights were also equipped with listening devices to help identify approaching aircraft. The primary role of the searchlights was the illumination of attacking enemy aircraft at night to permit more effective engagement by anti-aircraft guns and Royal Air Force night fighter aircraft. However, the lights were also used by the coastal defences to guide damaged friendly aircraft to a safe landing. The searchlights were coordinated to work together around the harbours and airfields of Malta. |

|

| An Italian MT M1940 Barchino explosive motor boat. Such boats were launched from a naval vessel and made their way through obstacles, such as anti-torpedo nets. The pilot would steer the boat toward its target and bail out before impact and warhead detonation. The cockpit is at the rear of the boat to balance the weight of the 330 kilogram (727.5 pound) warhead in the bow. Upon striking the target, a small explosive charge would shatter the boat's hull, allowing the warhead to sink and explode when its water-pressure fuze registered a depth of one metre (3.28 feet). In the early morning of 26 July 1941, a fleet of nine Barchini, two MAS motor torpedo boats, and two SLC (Siluro a Lenta Cors) 'human torpedoes' from the Italian navy's elite Decima Flottiglia MAS (10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla) mounted an attack on Malta's Grand Harbour. The human torpedoes failed to detonate, one motor torpedo boat was caught in the harbour's defensive net, and a second motor torpedo boat hit a pillar and exploded, blocking the entrance with debris. Alerted by the explosion, gun batteries at Fort St Elmo opened fire and destroyed the remaining Italian craft, while 18 Italian crewmen were taken prisoner. This particular Barchino was found abandoned 11 kilometres offshore following the 26 July attack and was subsequently towed to Manoel Island in Marsamxett Harbour and dismantled by a Royal Navy lieutenant. |

|

| A display case containing artefacts from the Italian explosive motorboat attack on the Grand Harbour, 26 July 1941: a fascio salvaged from Motoscafo Anti Sommergibile (MAS) 452 anti-submarine motorboat; a wooden badge displaying MAS 452 and the date of the attack on the Grand Harbour, presented by the Vice Admiral to the 1st Regiment of the Royal Malta Artillery; a sleeve rank of Sottotenente di vascello (Lieutenant Junior Grade) Roberto Frassetto; and a strap from the survival suit of an Italian MAS crewman. |

|

| Two compasses from Italian navy small craft, including one salvaged from an MT (Motoscafo da Turismo) explosive motor boat that participated in the unsuccessful attack on the Grand Harbour. |

|

| A large collection of old cannons now on display on the ramparts of Fort St Elmo. |

|

| The unrestored Lower Fort St Elmo. This part of the fortress was formed by the construction of the Carafa Enciente in 1689 and technically does not form part of Fort St Elmo. The three-storey barracks was built within this section in 1762 and was used by both the Order of St John and the British Army. It could house 1,340 soldiers in 1844. The first military prison on Malta was constructed within Lower Fort St Elmo in 1849. From 1964 to 1972, Lower Fort St Elmo was the home of the Malta Land Force and in 1978 it was used as the set of the film 'Midnight Express'. Lower Fort St Elmo is not currently under the responsibility of Heritage Malta. |

|

| Building 5 continues the story of Malta's Second World War experience up to the defeat of the Axis powers. |

|

| The lobby of Building 5 tells the story of life on Malta during the Second World War, with displays on civil defence, 'Victory Kitchens', news reporting, rationing, hospitals, and air raid shelters. An installation in the centre of the lobby depicts bombs dropping on shattered Maltese limestone masonry. One display also notes the role of women during the war, explaining how Maltese women worked with the armed services, the government, and in the dockyards. Women also volunteered with the Victory Kitchens or the Voluntary Aid Detachment staffing the general hospital, and treated wounded at advanced dressing stations. The Victory Kitchens were established in January 1942 when the government decided to prepare food centrally for the entire community in order to cut waste and ensure fair distribution. The kitchens were organised throughout Malta, with 42 in and around the Grand Harbour area by June 1943. People collected their meals to be eaten at home, with more than 175,536 people receiving meals from 170 Victory Kitchens in January 1943. Those who registered with the Victory Kitchens were asked to give part of their family ration of fats, preserved meat, and tinned fish to the kitchens; in return, they received cooked food, such as hot pot meals and pork or goat stews. Penalties for stealing food in Malta during the war were harsh, with theft of a tin of meat from the docks carrying a 30-day jail sentence. |

|

| This display contains information on Malta's air raid shelters, many of which were located in tunnels, caves, and catacombs across the island which were surveyed and adapted as needed. Some of the shelters became the virtual homes of families for the duration of the Axis aerial bombing campaign against Malta, with people moving chairs and beds, chamber pots, and cooking equipment into the shelters. During 1941, 1,500 men of the Shelter Constructing Department worked to build sufficient shelters, with each shelter occupant being allocated a mere 0.37 square metres (4 square feet) of space. Some families also excavated their own shelters. |

|

| This gallery is devoted to telling the harrowing story of the vital convoys that kept Malta supplied with food, ammunition, fuel, and other necessities and which suffered terrible losses at the hands of Axis air and naval forces in their attempt to strangle Malta into submission. The glass case displays a wide range of artefacts from the convoy battles and an animated depiction of the 'Pedestal' convoy of August 1942 is projected onto a large screen on the floor. |

|

| Items displayed here include life jackets from the merchant ships SS Almeria Lykes and Dorset; a life jacket from the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle; the bell from the carrier HMS Indomitable; and a Royal Navy life line hand gun. With Axis convoys between Italy and Libya suffering heavy losses at the hands of British aircraft, ships, and submarines operating from Malta, the German High Command decided to neutralise Malta by attacking the convoys keeping the island supplied with critical imports of food, fuel, medicines, and military goods. As a result of this Axis effort, Malta's civilian and military populace was almost out of food by June 1942 and British authorities dispatched a convoy from Gibraltar in August, codenamed 'Pedestal'. |

|

| A display on the merchant sailors, the unsung heroes of the convoys, who came from around the world and who fought their cargo ships through heavy Axis attacks to bring badly-needed supplies to Malta. The merchant sailors endured uncomfortable conditions and, if their ship was sunk, their pay was stopped on the day of the sinking. Many members of the Merchant Navy were awarded the King's Commendation for Brave Conduct during the war. Items displayed here include the name board, porthole hatch, and flag from the tanker SS Ohio. The Ohio was hit by bombs numerous times during 12-14 August 1942 but its crew managed to coax the severely damaged ship into the Grand Harbour where a large portion of its vital supply of fuel was offloaded. |

|

| A display of souvenirs crafted by Axis prisoners of war temporarily held in Malta's Corradino Military Detention Camp before being shipped to Britain. These souvenirs were a way for the prisoners to earn a bit of extra money to supplement the small allowances they were given. Picture frames, decorative boxes, crucifixes, ashtrays, cigarette lighters, and ink well sets were popular items made by the prisoners. In 1945, around 2,500 German prisoners of war were sent to Malta to perform agricultural work and assist in rebuilding infrastructure. They wore British khaki uniforms with round blue patches on their shirts to indicate their status. The last German prisoners on Malta were repatriated in 1948. |

|

| The original George Cross medal awarded to 'the Island Fortress of Malta' by King George VI on 15 April 1942 in recognition of the Maltese people's heroism and bravery in defying Axis attempts to starve the island into submission. Malta had been under almost constant attack by Axis forces from the date of Italy's entry into the war on 10 June 1940; hundreds of air raids, sometimes averaging seven per day, were carried out against Malta in the four-month period between January-April 1942 alone. Malta was the first British Commonwealth country to receive a bravery award. The George Cross is the highest award bestowed by the British government for non-operational gallantry or gallantry not in the presence of an enemy and is equal in stature to the Victoria Cross, the highest military award for valour. |

|

| A Willys Jeep brought to Malta by General Dwight D. Eisenhower in July 1943 for his use as Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Expeditionary Force preparing to invade Sicily. He named the jeep 'Husky' after the codename for the 10 July 1943 invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky), which was overseen from the underground war rooms in Valletta. Before he departed for Sicily to oversee the campaign, Eisenhower presented the jeep to Air Vice Marshall Sir Keith Park, Air Officer Commanding Malta. |

|

| The 'Husky' jeep was used by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he visited Malta on 8 December 1943. |

|

| A copy of the Times of Malta newspaper of 11 July 1943, announcing the Allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) on the previous day. This first step in the defeat of fascist Italy was launched from Malta, with General Dwight D. Eisenhower coordinating operations from the war rooms complex located deep under Valletta. Operation Husky involved over 2,700 ships and landing craft, aircraft and gliders, paratroopers, and army and navy personnel. Maltese military, labour force, and civilians played an important supporting role. Phase 1 of Operation Husky involved simultaneous amphibious assaults on the south coast of Sicily, supported by naval gunfire and strategic bombing. Within five weeks of the invasion, Allied forces had expelled all Axis defenders from Sicily, thereby opening the sea lanes through the Mediterranean to the Allies once again. Sicily would be the jumping-off point for the next Allied campaign, the invasion and liberation of Italy. |

|

| A captured Italian Cannone da 75/27 modello 11 on display in the last gallery of Building 5, devoted to the Allied victory over the Axis. Introduced in 1912, the French-designed, Italian-built Cannone da 75/27 modello 11 field gun was used by the Italian Army's alpine and cavalry troops in the First World War. The model remained in Italian Army service well into the Second World War, with many guns seeing service with German forces fighting in northern Italy from 1943 to the end of the war. |

|

| The top of the fort's cavalier, which housed a major artillery battery from the time the cavalier was built in 1556. This area witnessed some of the bloodiest moments in Fort St Elmo's history, from battles during the Great Siege of 1565 to Axis air strikes during the Second World War. From 1938, the cavalier platform also housed the Harbour Fire Command Post. Seen here is a memorial to six members of the Royal Malta Artillery who were killed by Italian bombs during an air attack on 11 June 1940, the first such attack on Malta during the Second World War; Fort St Elmo's cavalier was one of the first targets during the Axis aerial bombing campaign. |

|

| The 91.5 metre (300.2 foot) Dutch-built superyacht Tranquility enters Grand Harbour, as seen from atop Fort St Elmo's cavalier on 22 October 2023. Originally named Equanimity, the vessel was reportedly purchased by Malaysian financier Jho Low using money stolen from a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund. After being seized by Malaysian authorities in 2018, the superyacht was sold at auction in early 2019 and renamed Tranquility. It can accommodate 26 guests and 28 crew, and features a sauna, helicopter landing pad, swimming pool, gym, spa, cinema, and an on-deck jacuzzi, as well as two 10.5-metre tenders. |

|

| The Chart Room in Fort St Elmo's multi-level Fire Command Post, built atop the cavalier and facing the sea. The Fire Command Post was built prior to the Second World War and was designed to control all coastal artillery defending the Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour. The Chart Room featured a large table on which a detailed map of the Grand Harbour's environs was depicted. Any dubious items seen by the Fortress Observation Post at Fort St Elmo and the other forts forming part of the Harbour Fire Command were marked on this map. Information from the other forts was telephoned to Fort St Elmo's nearby Telephone Room. |

|

| The Fortress Observation Post (FOP), the watchful eye of the entire Harbour Fire Command. Here, soldiers with binoculars and other sighting equipment scanned the horizon for any sign of enemy ships or aircraft. Instruments, such as the Depression Position Finder, used to calculate the distance and position of possible targets at sea were mounted on the three columns in this room. The information was then passed to the Fire Commander in the Fire Command Post to give his orders to all fortifications. On 26 July 1941, the Harbour Fire Command system was put to the test for the first and only time when Italian explosive motor boats attacked the Grand Harbour; the system worked and the Italian attack was foiled by accurate artillery fire and the Italians' bad luck. |

|

| The Telephone Room was equipped with three telephone cabinets to receive and send communications between the fortifications of the Harbour Fire Command. It was also linked with the Malta Command complex at the Lascaris War Rooms in Valletta. Information received in the Telephone Room was passed to the Chart Room and the Fire Command Post through message pipes. This information was used by the Fire Commander to give orders for the aiming and firing of the various coastal defences mounted in Fort St Elmo and nearby forts, with these orders also transmitted back through the Telephone Room. |

|

| The reverse face of the cavalier (left) and the rear side of one of the barracks blocks on Piazza d'Armi. The cavalier was probably designed by Nicolo Bellavanti in 1556 and was originally detached from the rest of the fort by a defensive ditch and accessible by a drawbridge. The construction of the Carafa Enceinte in 1687 necessitated the reduction of the cavalier's footprint and the cavalier itself was incorporated within the fort in 1727. Additional modifications during the period of British rule after 1800 saw the cavalier strengthened and re-clad in concrete in order to accommodate large guns. |

|

| The National War Museum's Building 6 covers the period between 1946 and 2004, including post-war Malta, the country's independence, and its accession to the European Union. The exhibit is housed in a building originally constructed in the 1700s as a barracks but used as prison cells for members of the Order of St John found guilty of a crime. Political prisoners were also held here, including most of the rebels involved in the 1775 Uprising of the Priests and their ringleader, Dun Gejtan Mannarino. The British also used this building as a military prison by the 1830s. Additional prison cells were located underground and were reserved for the worst criminals. |

|