HMS Caroline is the latest addition to the network of museums collectively comprising the National Museum of the Royal Navy and is one of the maritime-themed attractions in the Titanic Quarter of Belfast, Northern Ireland. Listed on the National Historic Ships Register, she is one of three surviving Royal Navy warships from the First World War, and the only one that took part in the epic Battle of Jutland (31 May - 1 June 1916) between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet.

One of 28 C-class light cruisers built for the Royal Navy between 1914 and 1919, HMS Caroline was the lead ship of the class and the first of six sister ships comprising the Caroline sub-class. Her keel was laid on 28 January 1914 at the Cammell Laird shipyard in Birkenhead, England and Caroline was launched less than eight months later, on 21 September. Her construction cost £397,000, equivalent to £290 million in 2016. After fitting out and trials were completed, Caroline was commissioned into the Royal Navy on 4 December 1914 under Captain Ralph Crooke.

The six vessels of the Caroline sub-class were distinguished by their three raked funnels, with the 22 subsequent C-class cruisers featuring only two funnels due to an improved boiler and engine room layout. The speedy C-class light cruisers were designed to escort the battle fleet, scouting ahead to sight the enemy and defend it against attacking enemy torpedo boats, while also carrying out attacks on enemy light forces.

HMS Caroline's first posting was to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron at the Grand Fleet's base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. For the next six months, the ship undertook gunnery and torpedo exercises, fleet manoeuvres, and patrols in the North Sea, hunting for German naval vessels and checking neutral merchant ships for contraband. In June 1915, HMS Caroline underwent a three-week refit in Newcastle and then returned to Scapa Flow to continue routine patrols and exercises. To break the monotony of exercises and patrols, the ship's crew participated in football matches, boxing tournaments, and boat races, with the Concert Party putting on popular variety shows, such as 'Carry On', a concert and revue that was so popular after its first performance on 10 April 1916 that it was toured around the fleet.

On 31 May 1916, HMS Caroline, now serving with the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, was deployed with her squadron mates four miles ahead of the Grand Fleet, which had departed Scapa Flow for the waters off Denmark's Jutland peninsula in response to intelligence reports of the sortie of the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet. Upon the German fleet being sighted at 14:28, the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron was tasked with defending the Grand Fleet battleships against German torpedo boats and launching torpedo attacks against the enemy as required. As the opposing British and German battleships and battlecruisers engaged each other, HMS Caroline found herself in the midst of the action, being narrowly missed by German torpedoes, attacking a German destroyer, making an unsuccessful torpedo attack against the German battleship Nassau, and dodging enemy shells as she retired to Scapa Flow. At 12:50pm on 2 June, HMS Caroline arrived back at Scapa Flow, having missed the chaotic night phase of the Battle of Jutland. The next day, Caroline was back on patrol in the North Sea in support of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe's desire to show the Germans that it was 'business as usual' for the British fleet.

For the remainder of the First World War, HMS Caroline continued with exercises and North Sea patrols as part of the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, interrupted by a major refit in Glasgow in February 1917 and the installation of new propellers and additional searchlights in October 1918. When the Armistice was announced on 11 November 1918, HMS Caroline was still in the Newcastle dockyard. On 6 February 1919, Caroline was decommissioned and placed in 'Care and Maintenance'.

A little over four months later, on 27 June 1919, HMS Caroline was recommissioned under Captain William Law and departed two days later for Bombay, India where she joined the Royal Navy's East Indies Station, responsible for the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, and Red Sea. After arriving in Bombay on 28 July, Caroline was refitted and then spent the next two years visiting various ports in the region, including the Maldives, the Seychelles, Mauritius, and Aden, in order to 'show the flag'. Two years of steaming around the East Indies led to several defects in Caroline's steam turbines which could not be repaired by the Bombay dockyard. Ordered back to the UK for disposal, Caroline departed Colombo, Ceylon on 2 December 1921 and arrived at Portsmouth on 19 January 1922; due to the defects with her turbines, the ship never exceed 10 knots (18.5 km/h) during the long passage home. HMS Caroline was decommissioned on 17 February 1922 but remained tied up in Portsmouth for the next two years.

HMS Caroline avoided the shipbreakers in February 1924 when she was offered up as the static headquarters and training ship for the newly-established Ulster Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in Belfast. After being towed from Portsmouth to Belfast, the Harland & Wolff shipyard removed Caroline's guns and boilers, converting the cavernous boiler rooms into offices, classrooms, and workshops. A large steel drill hall was also installed aft of the funnels to permit year-round reservist training but other parts of the ship were left untouched. HMS Caroline recommissioned in her new role on 1 April 1924.

During the Second World War, HMS Caroline served as the headquarters of Belfast Naval Base and a base depot ship for minesweepers and small anti-submarine vessels operating from the city's port. Eventually, several thousand Royal Navy personnel would be administratively assigned to HMS Caroline as the base grew to occupy buildings across the city. Caroline provided communications and cypher facilities for her assigned fleet of anti-submarine trawlers, as well as trained gunners for the Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (DEMS) scheme. As the U-boat menace grew and the Battle of the Atlantic expanded, HMS Caroline's assigned anti-submarine fleet increased from 15 ships in July 1940 to 41 six weeks later and 70 by the end of the year. Later in the war, an office suite was built on HMS Caroline's aft superstructure to control the new escort groups of destroyers, frigates, and corvettes assigned to Belfast.

With the end of the war, HMS Caroline was decommissioned as a base ship on 31 January 1946 and returned to her role as drill ship for the Ulster Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. While naval reserve afloat training ships were scrapped elsewhere in the UK in the post-war period, Belfast's affection for HMS Caroline saved the ship from a similar fate. In 1951, the Admiralty contracted Harland & Wolff to refit Caroline. Workshops were installed for training shipwrights and joiners, as well as facilities for dismantling torpedoes and engine room machinery. Modern radar sets were installed and classrooms added to teach navigation and typing. Notwithstanding these investments in HMS Caroline, the Ulster Division struggled to recruit, declining to under 100 personnel in 1968. As a symbol of British governance of Northern Ireland, HMS Caroline was targeted by the Irish Republican Army during the 'Troubles', with the first attempted attack coming in 1956 when the IRA planted a time bomb on the dockside next to Caroline. In September 1971, an IRA sniper fired at the ship, while in August 1972 a bomb damaged the dockside gunnery school and caused minor damage to Caroline's superstructure.

After years of calls for HMS Caroline to be preserved and opened to the public, as well as an abandoned plan by the Imperial War Museum to acquire the ship in the 1990s, the opportunity came in December 2009 when the Ulster Division moved to a new facility ashore. On 31 March 2011, HMS Caroline was decommissioned for the last time and the ship came under the management of the National Museum of the Royal Navy on 13 April. After years of restoration and conservation work funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the Northern Ireland Department for the Economy, HMS Caroline opened to the public on 31 May 2016. Closed for nearly three years during the COVID-19 pandemic, HMS Caroline re-opened to the public on 1 April 2023. Over 110 years old, this remarkable ship provides a fascinating look at early 20th century naval ship design and construction and serves as a poignant memorial to the Battle of Jutland.

Specifications: HMS Caroline

Length overall: 135.94 metres (446 feet)

Beam: 12.65 metres (41 feet 6 inches)

Draught: 4.9 metres (16 feet)

Displacement: 3,750 tons

Propulsion: 8 x oil-fired Yarrow boilers generating 40,000 shaft horsepower and feeding 4 x Parsons direct drive turbines and 2 x Parsons cruising turbines connected to four propeller shafts

Speed: 30 knots (55.5 km/h)

Range: 3,680 nautical miles (6,820 km) at 18 knots (33 km/h)

Armament: 2 x 6-inch guns (later 4); 8 x Quick Firing 4-inch Mk IV guns (later 4); 1 x 6-pounder anti-aircraft gun (later 2 x 3-inch anti-aircraft guns); 2 x 21-inch twin torpedo tubes mountings and 12 Mk II torpedoes

Armour: 1-3 inch (25-76mm) belt armour along hull; 1 inch (25mm) deck armour

Crew: 289, consisting of 17 officers, 105 seamen, 13 boys, 89 Engine Room ratings, 36 'non-executive' ratings, and 29 Royal Marines. Complement increased to 361 in 1920 for service in the East Indies.

Photos taken 27 October 2024

|

| Approaching HMS Caroline, afloat in Belfast's Alexandra Graving Dock. This dock, constructed by the Belfast Harbour Commissioners between 1885 and 1889, was built partly on land reclaimed from the sea and partly in the waterway of the Victoria Channel. It measures 12 metres (40 feet) deep and its base and stepped sides are made of Portland cement and granite blocks. Opened by Prince Albert Victor of Wales on 21 May 1889, Alexandra Dock was constructed to promote local shipbuilding and provide a ship repair dock big enough to accommodate the large cargo vessels which called at the city's port. Open at one end, the dock's mouth could be sealed using a large iron floating caisson gate which would be filled with water to sink into place; the water in the dock would then be pumped out using steam-powered machinery in the adjacent Alexandra Dock Pump House. By the mid-20th century, the caisson gate was no longer fit for purpose and Alexandra Dock was allowed to flood permanently. |

|

| A stern view of HMS Caroline. The large amidships drill hall, added in 1924 when she began life as a headquarters and static drill ship for the Ulster Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, can be seen. Given how long HMS Caroline served as a static administrative and training establishment, it was decided to retain the drill hall during restoration work to reflect this important part of the vessel's history. |

|

| A closer look at HMS Caroline's port side, including the large drill hall installed aft of the ship's three funnels. The drill hall was added to accommodate administrative and training facilities for the ship's static postwar role, with the large enclosed space allowing Belfast's naval reserve unit to muster and train regardless of the weather. |

|

| HMS Caroline's three funnels are prominent features of the Caroline sub-class of the C-class light cruiser design. Of the 28 C-class light cruisers built between 1914 and 1919, only the six vessels of the Caroline sub-class had three funnels, with all subsequent sub-classes being given a more efficient boiler layout which permitted a reduction to two funnels. |

|

| A closer look at the port side main deck of HMS Caroline. The ship's boats would originally have hung from the curved davits. The tripod mast supports a crow's nest for lookouts in the era before radar, as well as a number of halyards for hoisting signal flags and radio wires strung between the forward and main masts. |

|

| A port bow view of HMS Caroline. The ship's forecastle sports four 4-inch guns, two mounted forward of the bridge and two flanking the bridge. |

|

| A view of HMS Caroline from directly in front, showing the ship's fine beam and the flare of the bow. Due to their slender hulls, the C-class cruisers were notorious for their propensity to roll (sometimes up to 30 degrees) in heavy seas, flooding mess decks and damaging equipment. |

|

| A starboard bow view of HMS Caroline. The ship's paint scheme is based on a tiny area of original First World War paint found aboard during restoration efforts in 2011-16. |

|

| A closer view of HMS Caroline's forecastle and mast, as well as the open-air Navigating Bridge with the Fore Control Position on top. It was from the Navigating Bridge that the ship was commanded, with targets and firing instructions being communicated to the guns and torpedo tubes via telephone and voice pipe from the Fore and Aft Control Positions. Originally, each bridge wing accommodated a large signalling lamp and a semaphore mast with two movable arms for visual signalling to other ships. Two of the ship's replica 4-inch guns are also visible; during a major refit in February 1917, the forward pair of 4-inch guns were removed and replaced with a single centreline-mounted 6-inch gun. |

|

| A port beam view of HMS Caroline, from the Navigating Bridge aft to the amidships drill hall. Two twin sets of torpedo tubes were mounted on the deck just aft of No. 3 funnel (where the drill hall currently sits), one each on the port and starboard sides. HMS Caroline carried up to twelve 21-inch diameter Mk II torpedoes, each weighing 1,500 kilograms and capable of travelling up to 4,000 yards (3.6 km) at a speed of 45 knots (83 km/h). Four torpedoes were carried in the tubes, with an additional eight reloads stored below decks in the Torpedo Bodies Workshop; the torpedo warheads were stored separately in the magazine. |

|

| Looking aft along the starboard side. The starboard midships 4-inch gun is visible; prior to the installation of the large drill hall, a second pair of 4-inch guns were mounted along the waist, one on each side of the ship just aft of the third funnel. |

|

| A view of HMS Caroline, showing the rounded cruiser stern and the pair of aft-facing super-firing 6-inch guns. |

|

| Venturing up the gangway to tour HMS Caroline. Wire aerials strung between the forward mast and mainmast were used for long-distance wireless communications using Morse code in the era before voice (radio) communication. |

|

| Visitors to HMS Caroline begin their tour in the large amidships drill hall, which now contains displays on the ship's design, the competition between the Royal Navy and the Imperial German Navy in the prelude to the First World War, and the 31 May-1 June 1916 Battle of Jutland, in which HMS Caroline took part. This massive naval battle, fought over the course of 36 hours, involved 250 British and German warships manned by an estimated 100,000 sailors. |

|

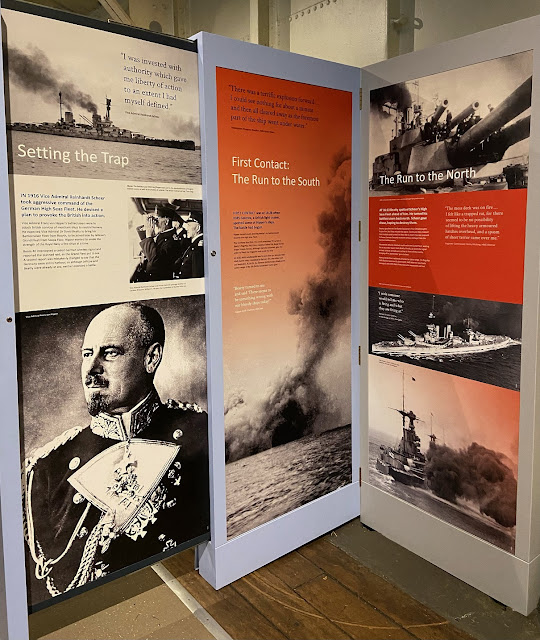

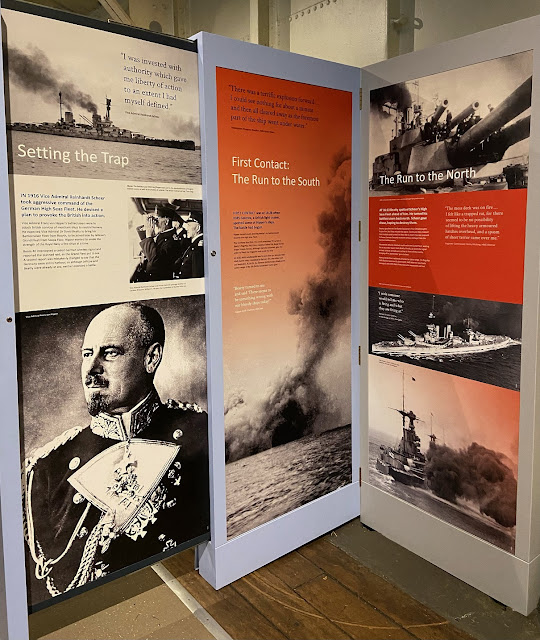

| A display on the early stages of the Battle of Jutland, including the German plan to draw out the British Grand Fleet into the jaws of the waiting German High Seas Fleet, and the initial contacts between the two fleets. The clash of the British and German navies would see 25 ships sunk and over 8,500 killed (including 350 Irishmen), with the Royal Navy suffering the majority of the losses but winning a strategic victory as it retained control of the North Sea. While the Grand Fleet was ready for action the day after the battle, the High Seas Fleet largely remained in port for the remainder of the war, with Germany opting to focus on submarine warfare against Britain's merchant trade. Demoralised German sailors of the High Seas Fleet mutinied in early November 1918 and the fleet surrendered to the British at Scapa Flow later that month following signature of the Armistice. The interned German ships were scuttled by their own crews on 21 June 1919 in a final act of defiance. |

Below: Projected onto the side of the drill hall interior is a film dramatising the Battle of Jutland and HMS Caroline's role in it. When the film ends, visitors are taken on a guided tour of the ship.

|

| Entering the aft deckhouse, where HMS Caroline's officers lived. This anteroom contains officer's heads (toilets) and a hatch leading down to the deck below. |

|

| One of the ship's officers' heads. The toilet is located on a raised platform in event that water entered the aft deckhouse during heavy seas. |

|

| The officer's flats, containing small cabins for some of the ship's 17 officers. Additional officers' cabins are located one deck below. |

|

| The cabin of Staff Surgeon George Deane Bateman, posted to HMS Caroline on 24 November 1914. |

|

| The cabin of Lieutenant Commander Eric Reid Corson, posted to HMS Caroline from 13 November 1915 to 2 June 1918. |

|

| The Captain's day cabin, located at the far end of the aft deckhouse, was where HMS Caroline's commanding officer slept, ate, and worked when the ship was on routine patrol or in port; a small sea cabin was located adjacent to the bridge for the Captain's use when he needed immediate access to the bridge. A small coal-fired stove provided warmth during patrols in the cold North Sea. |

|

| The Captain's desk for routine administrative work and a couple of armchairs for relaxing. |

|

| The Captain's pantry, where a steward plated meals for the Captain and any officers or guests invited to dine. |

|

| The window between the pantry and the day cabin was used to pass plates to the steward serving the Captain and any guests joining him. |

|

| A view of the Captain's day cabin, with the dining area on the left, office on the right, and bedroom and en suite bathroom through the door on the right. |

|

| The Captain's austere bedroom. |

|

| The Captain's en suite bathroom, the only private bathroom aboard HMS Caroline. |

|

| The Captain's private head. |

|

| Leaving the Captain's day cabin, the tour exits the aft deckhouse and continues out onto the Quarterdeck. |

|

| A replica of one of the ship's two breech-loading 6-inch (152mm) Mk XII guns. The other replica 6-in gun is located on top of the aft deckhouse, above the Captain's day cabin. Such 6-inch guns were the primary armament on light cruisers commissioned during the period 1914-26 and were fitted to all 28 of the C-class cruisers built for the Royal Navy. Given the role of light cruisers in scouting ahead of the battlefleet to locate the enemy, HMS Caroline's two 6-inch guns faced aft to return fire from pursuing enemy cruisers. During a major refit in February 1917, an additional 6-inch gun was installed on the forecastle, replacing two of Caroline's forward-facing 4-inch guns. |

|

| The breech end of the replica 6-inch gun on the Quarterdeck. HMS Caroline's replica guns were manufactured by the Titanic Studios, a film production facility located nearby, the original guns having been removed when the ship was converted into a static headquarters and training establishment in Belfast. |

|

| Visitors descend through a hatch on the Quarterdeck to a deck containing more accommodation spaces. Officers were housed at the aft end of the ship, with non-commissioned officers and ratings housed forward. |

|

| An officer's cabin. |

|

| A passageway leads toward the stern and the officer's bathroom. |

|

| Two bathtubs in the stern for officers. Access to the tubs was according to seniority, with junior officers forced to wait until their superiors had bathed. |

|

| The cabin of Paymaster Ernest William Cox, posted to HMS Caroline from 19 November 1914 to 16 April 1917. |

|

| The hatch leading down to the Tiller Flats, the ship's emergency steering position should the wheelhouse be put out of action. Due to the cramped size of the Tiller Flats, visitors are not permitted in, though a photo is pasted to the bulkhead on the left. |

|

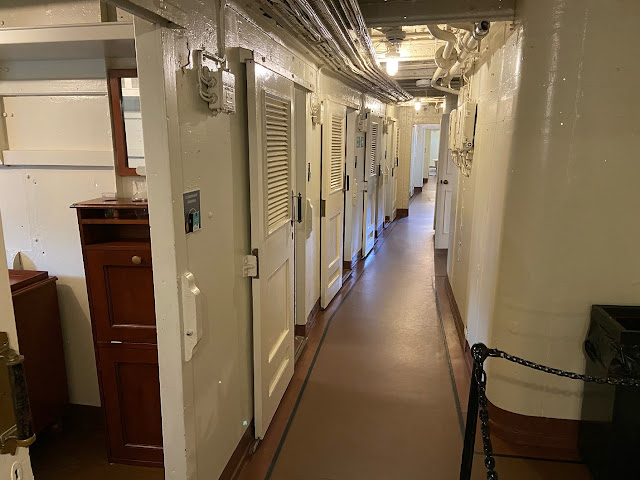

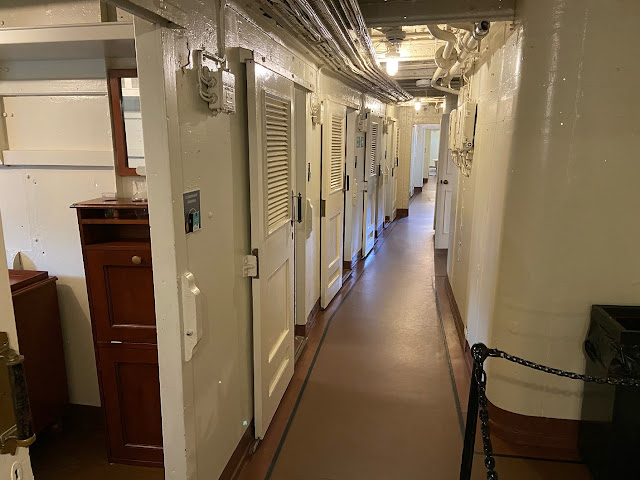

| Heading forward along the passageway, past additional officers' cabins and the ship's office. |

|

| The ship's office. |

|

| Another officer's cabin. |

|

| The Wardroom, where the ship's officers (except the Captain) ate their meals and relaxed. With limited heating and ventilation onboard, the Wardroom had a coal-fired stove in the corner to provide additional warmth. |

|

| The Wardroom is dominated by the large dining table. The 'president' of the Wardroom was the First Lieutenant (the Executive Officer), at the rank of Lieutenant Commander. The other 16 officers included three lieutenants responsible for gunnery and navigation, two Engineering officers, two Surgeons, and two Paymasters, with the remainder being junior officers. |

|

| The officers' meals were prepared in a dedicated officers' galley and, as in the Captain's day cabin, plated in the adjacent pantry, being passed through the hatch to the sideboard where they were served to the officers by the Wardroom stewards. |

|

| Continuing forward along the passageway, past the cabin of Lieutenant Commander Robert Standring, on the left. Standring, an officer in the Royal Naval Reserve, was posted to HMS Caroline on 24 November 1914. |

|

| The Marines' Mess or 'Barracks', where the ship's complement of Royal Marines slept and ate. The Royal Marines detachment was responsible for providing landing parties and also worked some of the ship's guns in combat. |

|

| Hammocks hang from the deckhead in the Marines' Mess to provide visitors a sense of the limited space afforded to each crewman. |

|

| The Stewards' Mess, where those men assigned as stewards to the officers dined. The space can be curtained off to avoid disturbing other men who might be sleeping while off duty. |

|

| Looking down through a grating over a hatch leading to lower decks currently inaccessible to visitors. |

|

| This compartment has been converted to house displays on naval communications aboard HMS Caroline. In the early 20th century, no signalling systems were totally reliable, with visual signals (flags, semaphore) reliant on clear weather and the relatively new and primitive wireless telegraphy using Morse code vulnerable to interception and jamming by the enemy; the volume of wireless transmissions from the ships of a fleet could also overwhelm wireless operators with 'noise' obscuring the truly important signals. Wireless aerials, flag signals, signalling lamps, and semaphore masts were all vulnerable to being shot away during combat, leaving a ship without means of conveying important messages. One of the displays recounts the British capture of German naval codebooks in 1914 and the establishment of the Room 40 codebreaking establishment at the Admiralty in October of that year. It was a message decoded by Room 40 in May 1916 that was used to alert the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, that the German High Seas Fleet was preparing to sortie; in consequence, the Grand Fleet deployed into the North Sea and the Battle of Jutland was fought on 31 May. |

|

| The Engineers' Workshop, originally crowded with heavy-duty drills, lathes, shears, and shaping machines for working steel. As HMS Caroline's engines and boilers were required to work reliably at high speeds for long period of time, the ship's engineering staff used this workshop to repair faulty parts and manufacture replacements if required. |

|

| A scale model of one of HMS Caroline's four turbine engines, which used high pressure steam generated by the eight boilers to turn the ship's propeller shafts. |

|

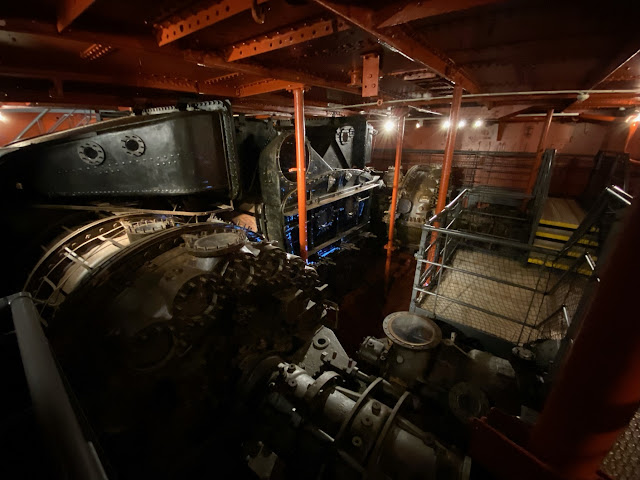

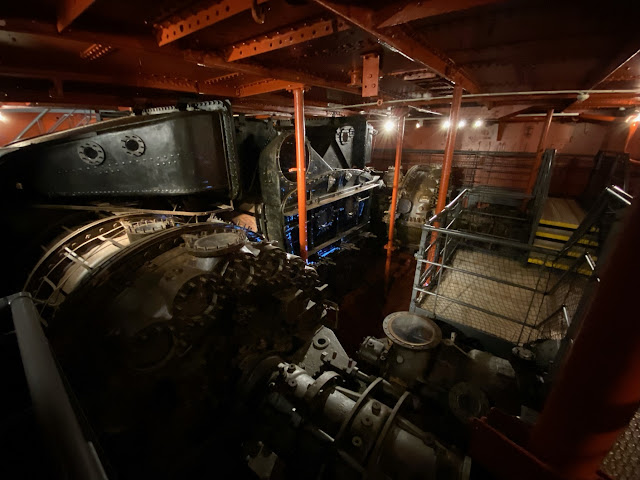

| Descending from the Engineers' Workshop, visitors enter No. 1 Engine Room. HMS Caroline's engines and boilers were overseen by the Engineer Commander and his crew of 92 men, representing nearly a third of the entire ship's company. Directly below the Engineer Commander were the Engine Room Artificers, educated men trained to operate and maintain all parts of a warship's engines. The enlisted engine room personnel were called stokers, a holdover from the days of coal-fired ships, when stokers were responsible for shovelling coal into the boilers. |

|

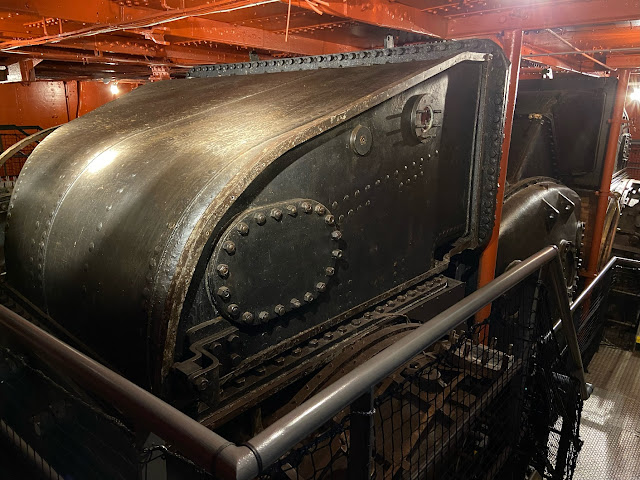

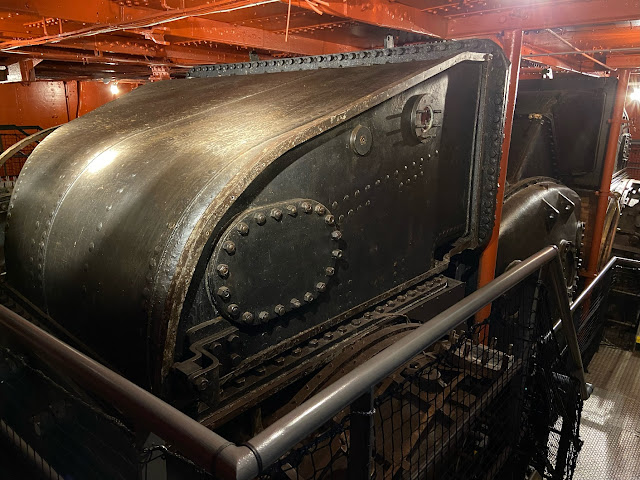

| HMS Caroline's four double reduction steam turbine engines are original from 1914, having been left in place when the ship was converted to its static training role in 1924. As such, these engines are among the earliest examples of steam turbines in the world today. The viewing platforms are the only new additions to this space, to enable visitors to better see the layout of the engine room. |

|

| High-pressure, superheated steam generated in eight oil-fired small-tube boilers (four boilers in each of two boiler rooms) was directed into the four large Parsons Impulse Reaction steam turbine engines. Each turbine drove a propeller shaft, with an additional cruising turbine connected to each of the two outer shafts to provide improved fuel economy when the ship was not in action. With the turbines generating 40,000 shaft horsepower, HMS Caroline's top speed was 30 knots (55.5 km/h; 33 mph). Unlike later sub-classes of the C-class light cruiser, the Caroline sub-class did not use gearing between the turbines and the propeller shafts; geared propulsion systems proved superior and were adopted for future turbine-powered vessels. |

|

| No. 1 Engine Room houses two turbines, while the remaining two turbines are housed in No. 2 Engine Room. This separation of engine rooms ensured that the ship was still capable of steaming, albeit at reduced speed, if one of the engine rooms was damaged. |

|

| A former mess deck, converted to house the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve division's Torpedo School in 1924, now contains displays on torpedo warfare and, seen here, the use of camouflage paint schemes on naval warships. In 1915, HMS Caroline took part in informal trials to test a paint scheme proposed by a Scottish zoologist which, based on wild animals, used 'compensating shading' and 'parti-colouring' to break up the outline of a ship. The Admiralty rejected this scheme and the Royal Navy's ships were painted a combination of dark and light grey. Only in August 1917 was marine artist and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve officer Norman Wilkinson's disruptive camouflage pattern, called 'Dazzle Painting', adopted by the Royal Navy. Dazzle Painting was intended to distort the appearance of a ship rather than try to make it invisible, thereby misleading and confusing the enemy's assessment of a ship's course, speed, and size during an attack. |

|

| One of the communal lavatories for crewmen to wash themselves. There are no showers, but merely wash basins. |

|

| Looking aft, down the passageway between mess decks. Two of the watertight doors and their black latches can be seen in the distance. When preparing for action, HMS Caroline's crew would close key internal watertight doors between compartments to limit the extent of flooding if the ship was hit by a torpedo. If a torpedo attack was likely, the 'Alert' was sounded and all magazines, shell rooms, the torpedo room, and their associated ventilating pipes were sealed up, as were any doors left open to aid in transferring ammunition. If a torpedo was about to hit the ship, the 'General Collision Stations' alert was sounded by several short bugle or siren blasts, prompting all crewmen except those working in the engine and boiler rooms to evacuate to the Upper Deck. HMS Caroline fired her torpedoes during the Battle of Jutland and narrowly avoided being hit by torpedoes fired by German torpedo boats. |

|

| Below deck inside the forecastle, where the starboard leg of the ship's tripod mast passes through. The oval panel on the cylindrical mast leg covers the hatch through which crewmen entered to climb up to the ship's lookout platform in the upper mast. |

|

| One of the seamen's messes in the forecastle. Most of HMS Caroline's crew lived in two large mess decks in the forward part of the ship, each with space for up to 94 men to sleep, eat, and store their personal belongings. Each table, seating eight men, was a 'mess'. On a rotational basis, one man from each mess would be designated as the 'mess cook', responsible for collecting food from the galley at meal times and bringing it to his messmates here. |

|

| A closer look at a cabinet containing dishes, cutlery, and jars for tea, coffee, cocoa, and sugar in the mess deck. Each mess of eight men had its own set of dishes, as denoted by the numbers shown on the jars. |

|

| Another view of the Seamen's Mess Deck. Because of the limited heating and ventilation systems in the C-class cruisers, in the winter the men living here relied on coal-fired stoves for warmth and condensation built up on the deckheads and bulkheads, dripping on the men. During HMS Caroline's posting to the East Indies Station in 1919-1922, the interior of the ship became stiflingly hot and the men slept on the Upper Deck or rigged air scoops to the outside of mess deck portholes to direct air inside when the ship was sailing. The mess decks often became swamped with seawater when the narrow hull rolled in heavy seas, often by as much as 30 degrees from the vertical. |

|

| Anchor cables pass through the forward section of the Lower Deck. As depicted here, when not in use, hammocks were rolled and stowed in storage bins. |

|

| The Sick Bay, where sick or injured crewmen were treated by the ship's surgeons and medical personnel. |

|

| Child-friendly interactive displays are featured in this former forward mess deck. The flare of the hull is clearly evident in the sloping sides of the bulkheads. |

|

| Proceeding aft through the forecastle toward the hatch leading onto the open deck. The large, angled cylindrical structure on the right is one of the legs of the tripod mast installed on HMS Caroline in 1917. |

|

| Water-resistant oilskins hang in a cage in the forecastle. Crewmen going on duty as lookouts would don such oilskins to protect them against the driving wind, rain, and ocean spray and return them to the cage to dry after their watch ended. |

|

| Some of the crew's heads in the forecastle. |

|

| The ship's galley, located in the forecastle, under the forward mast. It was here that up to 360 meals per day were prepared for the crew. Food was basic but filling, with the menu for Christmas Eve 1914 consisting of bacon and mashed potatoes for breakfast, stew for dinner, bread and jam at teatime, and sardines for supper. Christmas dinner consisted of ham and 'duff' (plum pudding). Food prepared in the galley was picked up by the designated 'mess cooks' and delivered to each mess. |

|

| The steel tripod mast was installed during a refit in February 1917, replacing the ship's original pole mast. The hollow steel tripod legs contain rungs up which the lookouts climbed to reach the crow's nest. |

|

| The starboard waist Quick Firing (QF) 4-inch gun; another is located in the same position on the port side. Originally, a second pair of QF 4-inch guns was located on the port and starboard sides of the deck where the drill hall was installed, with an additional four QF 4-inch guns on the forecastle. The 4-inch guns were effective against enemy submarines and torpedo boats. |

|

| Shells for HMS Caroline's 4-inch guns, mounted on the deckhouse bulkhead near the gun for easy access in a firefight. |

|

| Looking forward on the port side, between No. 2 and No. 3 funnels. Ladders lead up to the forecastle and the Navigating Bridge, while the open hatch leads into the forecastle and the mess decks for the ratings. |

|

| A final look at HMS Caroline in Belfast's Alexandra Graving Dock. |