Located along the River Lagan in Belfast, Northern Ireland on the former industrial land known as Queen's Island, Titanic Belfast opened in 2012 as a star attraction of the city's Titanic Quarter development. The impressive modernist building sits next to the former design office where famous Belfast shipbuilder Harland & Wolff designed the White Star Line's Olympic class ocean liners and the two slipways where Olympic and Titanic were constructed between 1908 and 1911. Although Harland & Wolff continues to build and repair ships and its giant yellow cranes remain a fixture of the Belfast skyline, much of Queen's Island has been redeveloped as a tourism, entertainment, recreational, and residential district, with a number of maritime-related attractions and historic sites strung along the so-called 'Maritime Mile', from the Abercorn Basin, Hamilton Graving Dock, and the former Harland & Wolff design offices to the Great Light, HMS Caroline, and the giant Thompson Graving Dock.

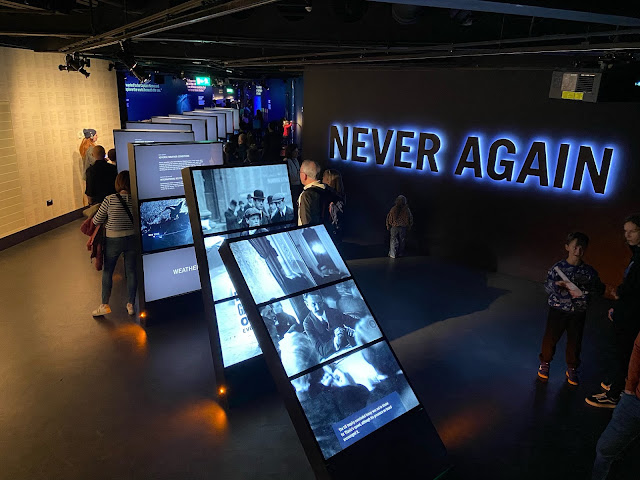

The jagged form of Titanic Belfast sits at the centre of this development. Inside, visitors to the paid Titanic Experience museum can learn about Belfast's rise as an industrial powerhouse and centre of shipbuilding and the conception, design, and construction of the Olympic class ocean liners built for the White Star Line. The museum exhibits naturally focus on the construction and disastrous maiden voyage of the doomed RMS Titanic, the ship's passengers and crew (both those who perished and those who survived), the discovery of Titanic's wreck over 70 years later, and the ship's enduring hold on the popular imagination over a century after its loss. Designed also as a focal point for the local community, Titanic Belfast includes a shop, restaurants, and event spaces.

Photos taken 27 October 2024

|

| One of the helpful maps installed along Belfast's Maritime Mile shows the location of Titanic Belfast, built alongside the River Lagan and adjacent to the original slipways on which RMS Titanic and her sisterships were built in 1908-1914. |

|

| The exterior of Titanic Belfast, the attraction dedicated to celebrating the design and construction of RMS Titanic and commemorating the doomed maiden voyage of the world's best known ocean liner. The huge steel plate with 'Titanic' in cut-out letters is 12 metres (39.4 feet) long and three metres (9.9 feet) high and is fashioned from the same 2.5 centimetre (1 inch) steel plate used to build Titanic; it is a very popular backdrop for photos. |

|

| The aluminum-clad exterior of Titanic Belfast evokes both the jagged shape of the iceberg that sank RMS Titanic and the massive angular bows of the transatlantic liners built in Belfast by Harland & Wolff. Titanic Belfast actually stands on the site formerly occupied by Harland & Wolff's plating sheds, where large steel hull and deck plates were fabricated for ships under construction in the nearby slipways. |

|

| A view of Titanic Belfast from the plaza surrounding the building. The plaza features a series of interpretive panels recounting the history of Belfast's Queen's Island district from 1785 to the present, as well as outlining the area's ongoing redevelopment plan to 2030. The six-storey Titanic Belfast structure includes underground parking in the basement level; a publicly-accessible ground floor with a ticket office, gift shop, and restaurants; the Titanic Experience museum on the first, third, and fourth floors; an education centre and gallery on the second floor; and a banqueting hall and hospitality suites for hire on the fifth and sixth floors. |

|

| Jutting out from the north side of Titanic Belfast is a section clad in blue glass and providing views out over the former Harland & Wolff Slips No. 2 and 3, in which the giant liners Olympic and Titanic were constructed. The paving stones of the plaza surrounding Titanic Belfast depict the northern hemisphere and a series of dot- and dash-shaped benches arcing around the perimeter spell out Titanic's Morse-code distress call 'SOS CQD' and the liner's own call sign 'DE MGY'. |

|

| Inside the main entrance doors are the ticket kiosks for those who have not pre-booked online tickets for the Titanic Experience attraction. |

|

| The Titanic Store, a large gift shop selling a range of Titanic-themed merchandise, occupies one corner of the spacious Grand Atrium at the building's centre. In addition to a wide range of books, toy, mugs, clothing, fridge magnets, and other Titanic souvenirs, the shop also sells Irish linen, fudge, and Belleek chinaware items. |

|

| The Galley on the ground floor of the Grand Atrium is the express food outlet for visitors to Titanic Belfast, offering soups, sandwiches, baked goods, specialty coffees and teas for 'grab and go' meals. |

|

| The Pantry, also located on the ground floor of the Grand Atrium serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner items made from fresh, seasonal Northern Irish ingredients. |

|

| The floors in Titanic Belfast's cathedral-like Grand Atrium are linked by a series of escalators. The restaurants and shop on the ground floor of the Grand Atrium are freely open to the public, with the museum entrance on the first floor requiring paid admission. |

|

| Looking over the railing and down to the bottom of the Grand Atrium from the upper floor of Titanic Belfast. The Grand Atrium, designed to evoke the feel of Titanic's cavernous engine rooms, spans five floors and is ringed by timber-decked balcony walkways. |

|

| The large annodised steel panels cladding an interior wall of the Grand Atrium are designed to resemble those used on the hull of the RMS Titanic, with the rusted finish evoking the look of the liner as she exists now, resting over 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) deep on the seabed. These panels in the Grand Atrium are only one-third the size of those installed on Titanic and a fraction of the thickness of Titanic's, which measured 2.5 centimetres thick. |

|

| The floor of the Grand Atrium features a large compass rose showing the cardinal points North, South, East, and West and the building's orientation. Around the edge of the compass rose is inscribed a verse from Men of Belfast by poet Thomas Carnduff, known as the 'Shipyard Poet': 'O city of sound and motion! O city of endless stir! From the dawn of a misty morning, To the fall of the evening air. From the night of moving shadows, To the sound of the shipyard horn. We hail thee, Queen of the Northland, We who are Belfast born.' |

|

| Visitors enter the Titanic Experience, the museum telling the story of Belfast's rise as a major shipbuilding centre, the design and construction of the Olympic class ocean liners, the RMS Titanic's tragic sinking in April 1912, the discovery of her wreck over 70 years later, and her ongoing influence on the popular imagination. Admission is by paid ticket, with a staff member scanning tickets at the entrance. |

|

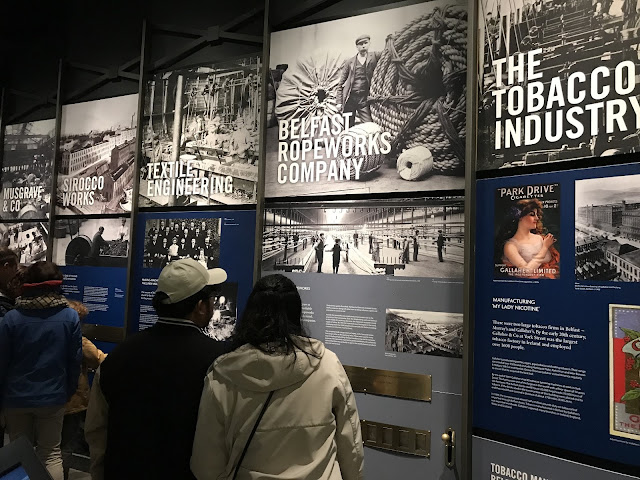

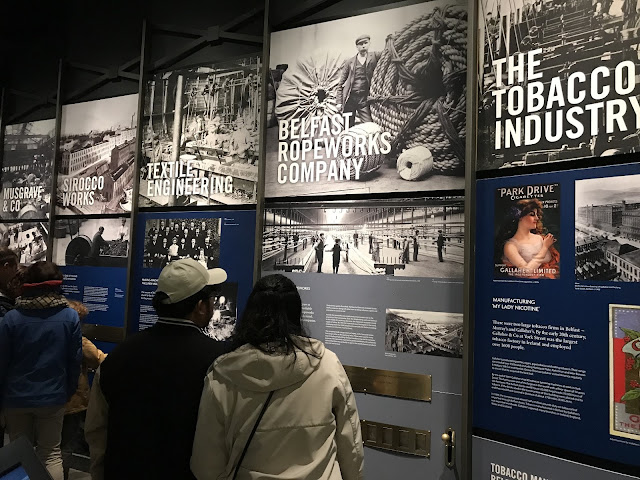

| The introductory galleries in the Titanic Experience tell the story of the rise of Belfast as a manufacturing and industrial centre in the 18th and 19th centuries. Displays cover individual sectors, starting with Belfast's industrial linen weaving industry, which led to the city's nickname of 'Linenopolis'. Other displays are dedicated to the city's whiskey, tobacco, ropemaking, textile engineering, soft drink, and shipbuilding industries. |

|

| A display on Belfast's docks and dock workers. Lacking access to local raw materials and energy supplies critical to industrialisation, Belfast relied on imports brought in by ship to the city's docks. Sugar, tobacco, and agricultural produce was imported through the docks from the 1700s and, later, large quantities of coal were imported to feed the steam-powered industrial machinery. Linen and other manufactured goods, such as machinery, cigarettes, whiskey, and soft drinks, were exported through the Belfast docks, with the duties paid on these goods contributing significantly to Crown revenues. Belfast was the fastest cargo discharging port in the world in the early 1900s, though dock workers were paid low wages for dangerous, physically demanding work that often amounted to 68 hours a week. Dock work was also often casual and offered no job security, with economic downturns causing mass layoffs. Over 6,000 dockers and carters were employed on the Belfast docks in 1907, with dockers loading and unloading the ships and carters hauling cargo to and from the docks using horse carts. Such work continued in all weather conditions, with injuries and deaths common, often caused by falling into the river or being crushed. A strike by disgruntled dockers and carters in 1907 caused significant economic disruption in Belfast and when the local police sided with the strikers, warships were sent into Belfast Lough and soldiers into the city streets to restore order. Despite the strike, conditions did little to improve conditions for the dockers and carters. |

|

| Two plates advertising Ross's tonic water and Belfast ginger ale, respectively. By the mid-1800s, Belfast was home to several small firms producing 'aerated waters', or carbonated beverages. WA Ross & Company was established in 1879 in Belfast's Victoria Square, with its factory drawing pure water from the Cromac Springs via a 68.8 metre (226 foot) deep well. Carbonic gas and flavoured syrups were added to make the 20+ different aerated water products sold by the company. These included Royal Ginger Ale and Belfast Dry Ginger Ale. Ross's carbonated beverages were sold worldwide, especially to America and the overseas British colonies and were especially popular in places where local drinking water was unsafe due to diseases like cholera. By 1889, Ross's was manufacturing 36,000 bottles of carbonated drinks per day. Aerated waters made by Belfast companies were stocked by railway and steamship companies, as well as clubs and hotels. |

|

| A display on European emigration to Canada and the United States. Facing poverty and insufficient land at home or inspired by a sense of adventure and the job opportunities available to them, over eight million Europeans left for North America in the first decade of the 20th century. As a shipbuilding city, Belfast prospered building the emigrant ships needed to transport these people overseas. The ships became more comfortable, with Third Class accommodations replacing steerage class and dormitories being replaced with cabins and proper toilet facilities. Wealthier emigrants travelled on White Star Line or Cunard Line express steamships departing from Southampton for New York. Indeed, by 1910, Southampton was one of the principal European steamship departure points, along with Cherbourg, France and ports in Germany and Italy. |

|

| The dark gallery is punctuated by illuminated displays on Belfast's economic history and large photos and maps. These serve to provide historical context as visitors move toward the story of Titanic's conception, design, and construction. |

|

| The entrance to an exhibit devoted to the history of Belfast's shipbuilding industry, dating back to the early 1600s. Shipbuilding in Belfast became a major industry from 1791 and, during the mid-1800s, the Belfast Harbour Commissioners directed work to improve the flow of the River Lagan and expand the harbour and its shipbuilding infrastructure. Such efforts led to a further flourishing of the shipbuilding trade. In 1854, Edward Harland was hired as manager of a Belfast shipyard owned by Robert Hickson, with Gustav Wolff serving as Harland's assistant; however, in 1861, Hickson sold the yard to Harland and, in 1861, Harland and Wolff formalised their partnership. The Harland & Wolff firm quickly forged a reputation as builders of quality ships, combining new technologies with innovative naval architecture. The company was kept busy building and repairing the many ships required to transport emigrants to North America and to carry the expanding volume of trade across the Atlantic. By 1900, Harland & Wolff's sprawling shipyard was the largest in the world, covering 80 acres and employing 10,000 people; it was considered the most important shipbuilding firm in the United Kingdom. In 1870, Harland & Wolff began a long relationship with the White Star steamship line, building all but one of White Star's fleet until the outbreak of the First World War. |

|

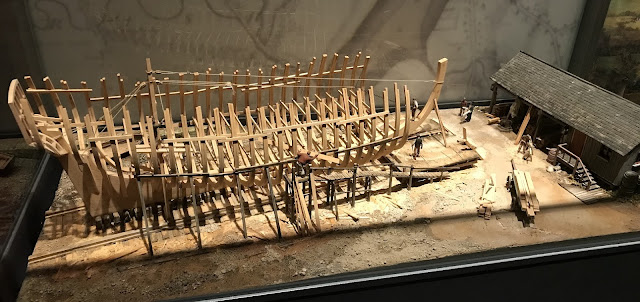

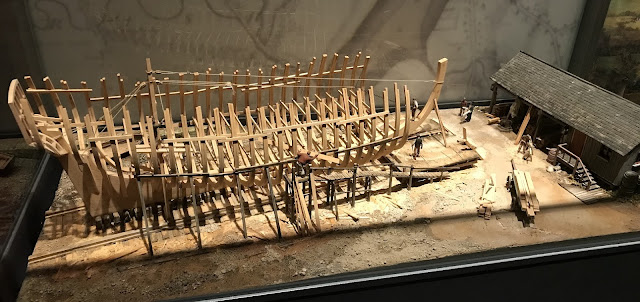

| A diorama depicts a small wooden merchant ship under construction at a simple shipyard in the early 1800s. Later in the century, large shipyards like Harland & Wolff covered acres along Belfast's River Lagan and employed thousands of skilled and semi-skilled labourers to construct massive iron and steel oceangoing ships. |

|

| The original document confirming the official change of name of the Queen's Island Shipbuilding & Engineering Company to Harland & Wolff Ltd., as agreed at extraordinary general meetings of the company on 5 and 20 June 1888. The document is signed by Sir Edward Harland, the Chairman of the company. |

|

| A time clock from Belfast's Harland & Wolff shipyard used by employees to record their time in and out of work. During Titanic's construction, workmen were given a small wooden time-keeping board at the start of each day and returned it as they left at the end of the day. Time clocks were eventually introduced to more accurately record workers' hours as a means of preventing 'time theft'. |

|

| An iron gate which once marked the boundary of Queen's Island, home to the Harland & Wolff shipyard. Every day, thousands of Harland & Wolff employees passed through this gate on their way to and from their shipbuilding jobs. |

|

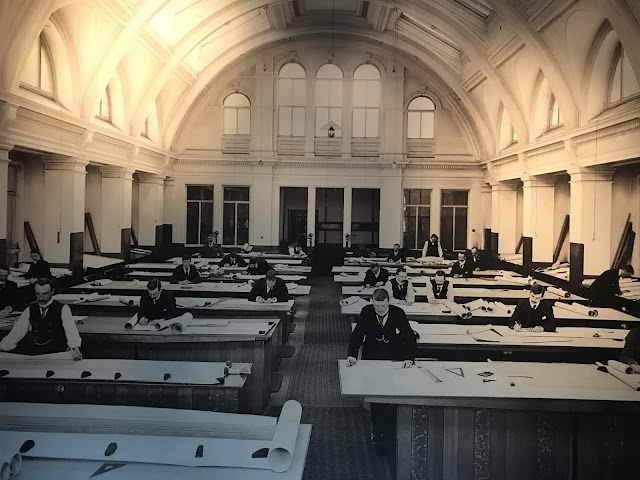

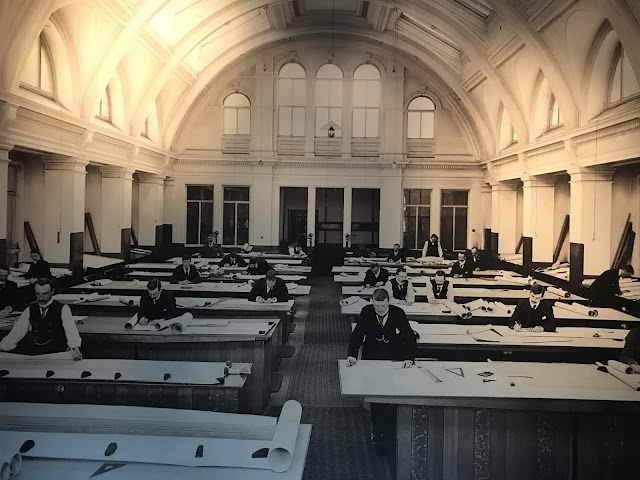

| A gallery telling the story of the conception and design of the Olympic class ocean liners Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic, as well as the roles of those involved in their construction, from the white collar managers and designers to the blue collar skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled shipyard workers. The gallery is designed to evoke the Harland & Wolff drawing office, with its barrel-vaulted ceiling. |

|

| One end of the gallery is dominated by a large wall-sized photo of the Harland & Wolff drawing office in 1912. It was here that skilled draughtsmen prepared detailed working drawings and plans of every part of a ship for use by the shipyard workers. The vaulted ceiling of the room, large windows, and bright overhead fan lights maximised the light to assist the draughtsmen in preparing their technical drawings. |

|

| After passing through the gallery on the design of the Olympic class ships, visitors walk around the base of a reproduction of one of the 11 columns of the Arrol Gantry and ascend in an elevator to an upper floor of the museum. The Arrol Gantry was a massive steel structure built over the Harland & Wolff shipyard's Nos. 2 & 3 slipways to support the heavy cranes and travelling frames used to move equipment and building materials required for the ocean liners under construction. It was named after Sir William Arrol, whose Glasgow-based engineering company built the gantry prior to the start of construction on Olympic and Titanic in 1908. Elevators and walkways provided workmen with access across the gantry and onto the ships under construction. The 6,000-ton Arrol Gantry was 256 metres (840 feet) long, 82.3 metres (270 feet) wide, and stood 69.5 metres (228 feet) high; it could be seen from most parts of the city. The Arrol Gantry was demolished in the 1960s. |

|

| After taking the elevator up the side of the gantry column, visitors follow the walkway toward the gallery telling the story of Titanic's construction. |

|

| The Shipyard Ride is a short theme park-style dark ride attraction travelling on an overhead track. Visitors board one of the ride cars and are taken through a mocked up shipyard, complete with the sound of hammering and riveting and the voices of shipyard workers describing their jobs piped in via the car's speakers. |

|

| A display on the work and tools of the shipyard riveters, as seen from the ride car as it twists and turns along the track of the Shipyard Ride. Through sound effects, dynamic lighting, and heat, visitors get a brief sense of what work in the Harland & Wolff shipyard during Titanic's construction must have been like. |

|

| After disembarking from the Shipyard Ride, visitors proceed past a series of panels describing various aspects of Titanic's construction. These include the laying of the ship's keel on 31 March 1909, framing, plating and riveting, construction of Titanic's 15 watertight bulkheads, and mounting the 23.7 metre (78 foot) tall, 100-ton rudder. The misplaced belief in Titanic's 'unsinkability' was based on her watertight compartments and the claim that the ship could stay afloat even if three of her forward compartments were flooded; however, the watertight bulkheads only extended up to E and D decks, depending on their location. |

|

| Visitors move into the gallery on Titanic's launch on 31 May 1911. |

|

| This gallery tells the story of Titanic's launch on 31 May 1911, 26 months after her keel was laid in Slip No. 3. At launching, Titanic weighed 24,360 tons and was the largest moving object ever built by man. As was the custom for White Star Line, there was no christening ceremony performed at the launch of Titanic and the shipyard workers removed the wooden blocks supporting the hull so that the ship could slide down the inclined slipway, which had been greased with tallow, train oil, and soft soap to minimise friction. To the loud cheers of the 100,000 people assembled to watch the launch, Titanic began sliding down the slipway into the River Lagan at 12:13 pm at a speed of 14 miles per hour (22 kilometres per hour), taking 62 seconds to complete. To keep the ship from drifting too far into the river, two piles of drag chains, each weighing 80 tons, as well as six huge anchors attached to the hull brought Titanic to a standstill. |

|

| The gallery on Titanic's launch features large floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the actual slipways where Titanic and Olympic were constructed, side-by-side, between 1908 and 1911. The lines of vertical posts mark the positions of the columns which supported the massive Arrol Gantry which once towered over the slipways until its demolition in the 1960s. The white lines on the slipways trace the outlines of the hulls of the two liners, providing visitors with a sense of the proportions of the Olympic class ships. |

|

| The next gallery is devoted to Titanic's fitting out, with displays on the installation of the ship's engines, boilers, funnels, and propellers, as well as the interior decoration of cabins and public spaces, and the selection of linens and crockery. |

|

| A 1:48 scale port side model of Titanic as launched on 31 May 1911. When launched, Titanic was still missing her four tall funnels, propellers, and propulsion machinery, and her interior spaces were virtually empty. Only portable boilers to power winches to pull her to the dockside were installed. The ship's watertight hull was covered by steel plates measuring a maximum of 10.9 metres (36 feet) long by 1.8 metres (6 feet) wide and weighing up to 4.5 tons each. |

|

| A 1:48 scale starboard side model of Titanic as completed, following fitting out. All engineering elements (funnels, propellers) are installed and the upper decks are fully outfitted. |

|

| Displays on the fitting of Titanic's propulsion machinery. The ship's 29 coal-fired boilers were located in six boiler rooms on the Orlop Deck and drove the three engines and the electricity generating plant. The engines, each weighing around 1,000 tons, consisted of two reciprocating engines driving the outer propellers and a turbine engine driving the centreline propeller. Of Titanic's four funnels, three vented combustion gases from the boilers, while the fourth was a dummy used for ventilation. The ship's outer propellers were over seven metres (23 feet) in diameter, with the centreline propeller being slightly smaller, at five metres (16 feet six inches) in diameter. |

|

| A White Star Line promotional brochure from October 1911 advertising Olympic and Titanic, dubbed the 'World's largest and finest steamers'. This brochure was distributed by Beekman Tourist Co. of Boston, Massachusetts. |

|

| Enclosed behind large glass panels is a reproduction of the First Class 'Old Dutch Style' stateroom aboard Titanic. Designed by the Dutch firm of Mutters & Zoon, this was one of the most luxurious and expensive staterooms on the ship and would have been occupied by wealthy, elite passengers, such as members of the aristocracy or business magnates. One of several 'special' staterooms decorated in period style (e.g. Georgian, Italian Renaissance, French), the Old Dutch Style stateroom featured large windows to let in natural light, as well as electric lighting via a portable table lamp and wall and ceiling lights. A Royal Doulton washbasin with rouge marble countertop was flanked by oak wardrobes with bevelled mirrors and drawers and the sitting area was outfitted with a settee, table, and chairs. The walls featured carved oak panelling and wallpaper, while the panelled ceiling was adorned with oak beams. The beds were also crafted from carved oak. The Old Dutch Style stateroom was carpeted and included a heater, a wall tidy, an electric fan, and a push button bell to summon a steward. It had a shared private bath and toilet and a private wardrobe room. Prices for First Class cabins varied widely, depending on their style and size. First Class fares started at £26 per person, with cabins outfitted with one, two, three, or four berths. Larger families could book interconneecting suites and some large staterooms had small single-berth cabins for a servant. All First Class cabins were equipped with hot and cold running water, as well as wood or brass beds. The most expensive First Class staterooms were the parlour suites, with a private promenade. Sold for £870 during peak sailing dates, the parlour suites were outfitted to the highest standard, each suite featuring a large sitting room, two bedrooms, two wardrobe rooms, and a private bath and toilet. |

|

| A four-minute computer animation film shown on screens wrapping around three sides provides an immersive virtual tour of Titanic's interior, from her cavernous engine room up to the navigating bridge. |

|

| Visitors sit on the floor of the small wrap-around theatre showing a computer-generated looped film of what Titanic's interior looked like. Seen here is the sumptuously decorated à la carte restaurant. |

|

| The film proceeds up one of the iconic First Class staircases aboard Titanic. |

|

| The gallery on Titanic's fitting out addresses the ship's internal layout, which was extremely complicated due to the need to separate the different classes of passengers and provide the crew with access to all parts of the ship. Cargo, baggage, and mail storage areas on the ship were located so as to avoid disrupting onboard facilities and services, and many crewmen toiled out of sight of the passengers to ensure critical operations, such as food service and tending to the boilers and engines, did not interfere with passenger comfort. Improvements were made to Titanic's layout from experience with her sistership, Olympic. It took 3,000 workers and craftsmen 10 months to complete Titanic's fitting out. |

|

| The displays on Titanic's fitting out cover a wide range of topics, including the the installation of communications, navigation, heating and ventilation equipment, the onboard sanitary facilities, the design and decor of cabins and public spaces, the layout of crew accommodations and working areas, and the provision of onboard furniture, carpets, linens, pianos, and even ropes. Titanic was fitted with six pianos in public rooms: three in First Class (reception room, entrance hall, and dining saloon); two in Second Class (entrance hall and dining saloon); and one in Third Class (general room). With no onboard laundry facility, Titanic carried all the linens she needed for a voyage, including 45,000 table napkins, 18,000 bed sheets, and 10,000 cloths for food preparation. |

|

| Samples of carpet that were installed aboard Titanic. Three types of carpet were used on ships: Axminster, Wilton, and Hair. Axminster carpet's heavy, deep pile made it warm and luxurious, fit for such areas as the First Class reception room, reading and writing room, lounge, and period rooms. Titanic's Axminster carpets featured Empire wreath, Fleur de Lis, and Adam vase designs. Wilton carpet had a finer, closer weave, producing a 'velvet' pile suitable for the Second Class library. Wilton carpets could be either plain or highly detailed. Hair carpet, made from horse or cow hair, has a hard, tough pile that was more appropriate for less luxurious parts of the ship. Most of the carpets on Olympic and Titanic were woven in England and Scotland, with a few being made in Abbeyleix, County Laois, Ireland. |

|

| A First Class teapot. |

|

| A teapot, soup tureen, and bowl in White Star Line's Bradford Pattern. The Bradford Pattern was first registered on 31 July 1905 and was one of the china patterns used on Titanic's sistership, Olympic. |

|

| Plates decorated in the Bradford Pattern. |

|

| China cups and saucers, a sugar bowl, and a milk pitcher in the White Star Line's Bradford Pattern. Titanic carried more than 50,000 pieces of crockery for all three passenger classes. |

|

| White Star Line First Class bone china dishes, hand-decorated and with the steamship company's distinctive house flag decorating the centre of the plates. |

|

| Another pattern of White Star Line First Class tableware. |

|

| A white, utilitarian Third Class stoneware saucer featuring the White Star Line logo. |

|

| A Third Class stoneware mug. |

|

| A reproduction of one of Titanic's Second Class cabins, which was designed in a manner that it could be sold as both a Second Class or a First Class cabin. Second Class passengers were generally professionals, such as doctors, engineers, and highly killed workers, who paid fares starting at £9, 13 shillings, 6 pence from Queenstown, Ireland. Titanic's Second Class cabins were more luxurious than First Class cabins on other ships and came in either two- or four-berth configurations. They included mahogany bunks, mahogany wardrobes with mirrors inside, and upholstered settees. While Second Class cabins did not have hot and cold running water, the in-room washbasin did have a reservoir that was filled by the room steward. The walls were decorated in white panelling and public toilets and baths were located nearby. Second Class cabins designed to accommodate First Class passengers as required also featured heaters and carpeting. Other Second Class cabins were fitted with green-and-white or red-and-white linoleum tiles. It was in a Second Class cabin like this that the ship's bandmaster, Wallace Henry Hartley, was accommodated. While Hartley and his saloon orchestra entertained First and Second Class passengers during the voyage, after Titanic hit the iceberg, the band was ordered to play in the First Class lounge to calm nervous passengers. As the ship began sinking, the band moved to the boat deck and continued to play for passengers as they waited their turn to board the lifeboats. |

|

| The entrance to the gallery devoted to Titanic's maiden voyage, ending in disaster in the frigid North Atlantic. |

|

| Following sea trials in Belfast Lough, on 2 April 1912, Titanic set out for Southampton to embark her first passengers. During the voyage to Southampton, Titanic recorded her maximum speed of 23.25 knots (43 km/h). Arriving in Southampton at midnight on 4 April, Titanic moored at the White Star Dock, purpose built for the Olympic class liners. The White Star Line was the first large transatlantic steamship company to use the port of Southampton, which enjoyed rail links to London and easy access to and from Continental Europe. After loading passengers and cargo and conducting her first and only lifeboat drill at 9:00 am on 10 April, Titanic departed Southampton at noon, bound for Cherbourg, France. After embarking additional passengers and cargo in Cherbourg, Titanic sailed at 8:10 pm for Queenstown, Ireland, arriving there at 11:30 pm on 11 April. |

|

| The last photo of Titanic taken by Francis Browne, a photography enthusiast whose uncle gifted him a First Class ticket aboard Titanic between Southampton and Queenstown, Ireland. The photo was taken shortly after 1:55 pm on Thursday, 11 April from the stern of the tender America as Titanic departed Queenstown for her next and final destination, New York. The row boat being towed by America is one of several pilot boats at Queenstown that rowed out to Roche's Point to wait for Titanic as she sailed in from Cherbourg, France. |

|

| Visitors proceed chronologically past displays and photographs of Titanic at each of her ports of call, with the final display on New York, which the ship never reached. |

|

| A gallery depicting Titanic's aft promenade deck, complete with deck-edge railings and benches. Out of frame to the left, a video of the open ocean and horizon is projected on a large screen to simulate the feeling of being out on deck. |

|

| A mock-up of the entrance to Titanic's Verandah Café and Palm Court, located at the aft end of A Deck on either side of the Second Class staircase. A holographic Maître d'hôtel talks about the first rate service aboard the ship. The bright and airy Verandah Café and Palm Court had large floor-to-ceiling windows that provided expansive views of the ocean and was decorated with wicker tables and chairs, potted palms, and ivy-covered trellises. First Class passengers could enjoy light refreshments here, such as sandwiches and pastries, and stroll out to the aft promenade deck via sliding doors. |

|

| This First Class luncheon menu was given to Dr Washington Dodge by Titanic steward Frederick Dent Ray. The two men became friends on RMS Olympic and and, when both found themselves on sistership Titanic, Ray felt obliged to look after Dr Dodge after the the ship hit the iceberg. Ray escorted Dodge to Lifeboat No. 13 and gave the doctor this menu as a souvenir of their escape, underlining Titanic's name and the date, 14 April 1912. On the reverse side is inscribed 'With compliments & best wishes from Frederick Dent Ray, 56 Palmer Park, Reading, Berks.' |

|

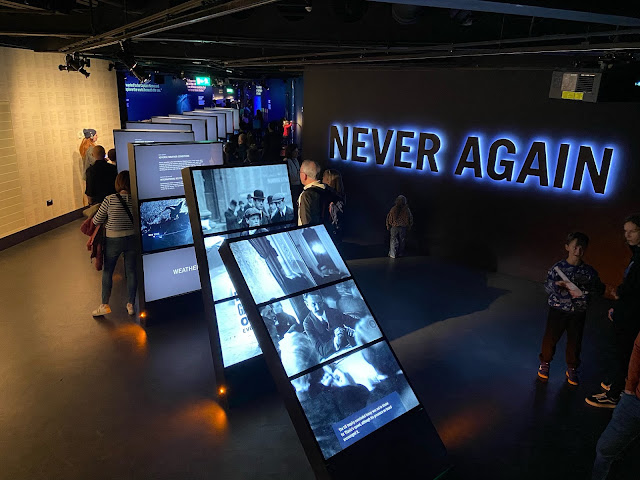

| The gallery devoted to Titanic's sinking presents animations of the various stages of the ship's sinking, paired with text panels showing the increasingly frantic Morse code messages sent by Titanic's wireless operator to nearby vessels. Titanic's first SOS message confirming the collision with the iceberg was sent to sistership Olympic at 12:45 am on 15 April, followed at 1:10 am with a message indicating that Titanic was sinking by the bows and requesting help as soon as possible. By 1:30 am, Titanic was signalling to Olympic, 'Cannot last much longer'. While Olympic was too far away to come to Titanic's rescue, Cunard Line's Carpathia arrived two hours after Titanic sank. |

|

| A display on the rescue of Titanic survivors by RMS Carpathia and their delivery to New York. Carpathia was the first ship to reach the scene of Titanic's sinking and picked up 713 passengers and crew, four of whom had died in the lifeboats or later aboard Carpathia. En route to Titanic, Carpathia's captain, Arthur Rostron, converted his ship's dining rooms into makeshift hospitals and prepared hot soup for Titanic survivors who were suffering from exposure in sub-zero temperatures in the open lifeboats. Although Halifax, Nova Scotia was the closer port, Carpathia delivered the Titanic survivors to New York to avoid icebergs and any further distress to the Titanic survivors. Carpathia reached New York at 9:30 pm on 18 April, watched by 30,000 curious New Yorkers and dozens of newspaper reporters and photographers looking to interview the exhausted Titanic survivors, many nursing injuries or still in a state of shock. |

|

| An original Fosbery lifejacket recovered from an unknown Titanic victim. This is one of only 12 surviving Titanic lifejackets out of the over 3,500 that were carried on the ship. Manufactured from linen and cork, this rare artefact was recovered by the crew of the Mackay-Bennett, the first of four ships chartered by the White Star Line to search for bodies after Titanic's sinking. |

|

| A huge digital wall in the gallery lists all the names of Titanic survivors and victims alphabetically, as well as a rotating set of statistics, such as the fact that 38% of the 1,303 passengers were saved. |

|

| The gallery devoted to the aftermath of the Titanic sinking, including the British and American inquiries into the disaster and the many maritime safety regulations and practices adopted as a result. |

|

As described by the illuminated displays, the Titanic disaster led to many important improvements in maritime safety. These included:

- The establishment of the International Ice Patrol to monitor icebergs in the North Atlantic and warn ships of danger;

- The prioritisation of urgent or safety-related messages over all other communications coming into ships' radio rooms;

- The requirement for ships to reduce speed or change course when ice is reported;

- Design regulations requiring that ships' watertight bulkheads be high enough to prevent water from spilling over into other compartments and that compartments be spaced in a manner that potential flooding will not tilt the ship;

- The provision of sufficient lifeboats for every person aboard;

- The maintenance of a proper lookout at all times to report any kind of hazard or risk of collision;

- The requirement that all passenger ships conduct a lifeboat drill for crew and passengers before leaving port and at least once a week during the voyage.

|

|

| Visitors learn about the discovery of Titanic's wreck by famed oceanographer and underwater archaeologist Robert Ballard. Ballard located pieces of debris on the seabed at 12:48 am on Sunday, 1 September 1985, with the main part of Titanic's wreck found the next day. The wreck lies in two main sections approximately 325 nautical miles (600 kilometres) south-southeast of Newfoundland and at a depth of around 3,800 metres (12,500 feet). The monitors in this display show clips from a documentary of Ballard's 1985 Titanic expedition. |

|

| A large multi-storey space is used for a haunting sound and light show interpreting Titanic's maiden voyage, from the excitement of passengers departing for America to the horrors of the sinking. A series of images and animations are projected on the walls while voices and sound effects are piped into the hall. Visitors descend from the upper level to the floor via a staircase around the edge of the room, leading to a series of Titanic artefacts. A glass floor section allows visitors to look down on a film of Titanic's wreckage on the seabed, captured by a remotely-operated submersible vehicle. |

|

| Suspended from the ceiling of the hall is a large wire mesh model of Titanic rigged with a series of coloured lights. The model rotates 360 degrees during the sound and light show, with the ship's lights coming on in sections to reflect Titanic's construction and, later, being gradually extinguished to symbolise the ship's sinking. |

|

| The model of Titanic with the ship's horizontal decks and vertical watertight bulkheads illuminated as the sound and light show depicts Titanic's construction. |

|

| An original deckchair from Titanic, recovered by the cable ship Mackay-Bennett, one of four ships chartered by White Star Line in the aftermath of the sinking to search for bodies. The deckchair bears the logo of the White Star Line on the headrest and a brass name tag holder on the rear. This is one of only six surviving deckchairs from Titanic. |

|

| An original Titanic deck plan showing the layout of First Class accommodations. Issued to First Class passengers to assist them in finding their way around the ship, this deck plan belonged to Ellen Bird, the personal maid of Ida Straus, whose husband owned New York's Macy's department store. Ms Bird's cabin, C-97, is marked with a cross and was directly across from the Straus's luxurious stateroom, C-55-57. Ida Straus and her husband Isidor both died after Ida refused a place on the lifeboat in order to remain with Isidor. Mrs Straus gave Ellen Bird her fur coat and insisted that the maid board a lifeboat; Ellen kept the deck plan until she died in September 1949. |

|

| A display of items belonging to 33-year old Third Class passenger Malkolm Joakim Johnson. Johnson drowned after Titanic sank and his body was recovered and, as with many of the Titanic victims, buried at Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax, Nova Scotia. On the left is Johnson's manifest ticket, stamped 10 April 1912, that he would have presented to immigration authorities upon arriving at Ellis Island in New York; Johnson was originally to have sailed on White Star's liner Adriatic but was transferred to Titanic due to a coal miners' strike. In the middle is a photograph of Johnson, a native of Sweden who had lived for many years in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The owner of a successful construction business, Johnson had travelled back to Sweden in an unsuccessful bid to purchase his childhood home and was returning to America when the Titanic sank. On the right is Johnson's Omega pocketwatch, which was recovered from his body and corroded in the seawater; the watch's hands are stopped at 1:37 am, when Johnson found himself in the icy water. |

|

| This display case holds the sheepskin coat of Titanic stewardess Mabel Bennett, who grabbed it before boarding a lifeboat. On the left is a silver hip flask belonging to Helen Churchill Candee who, lacking pockets in her coat, entrusted this family heirloom to fellow First Class passenger Edward Kent before she boarded a lifeboat; although Kent died in the frigid water, the hip flask was recovered with his body and returned to Ms Churchill Candee. On the right is a black-enamelled walking cane belonging to First Class passenger Ella White. As the cane had an electric light in the handle, White waved it around as a signal from the lifeboat she boarded; unfortunately, as Titanic's Second Officer later complained, White's actions blinded crew members trying to help load passengers into the boats. |

|

| This sterling silver loving cup was presented to Arthur Henry Rostron, captain of the rescue ship Carpathia, by Titanic survivor Margaret Brown during a ceremony in New York on 29 May 1912. Brown, a First Class passenger who garnered the nickname 'the Unsinkable Molly Brown', gave medals to Carpathia's crew members, chaired the fund-raising effort for the Titanic Survivors' Committee, helped erect the Titanic Memorial in Washington, DC, and visited the Fairview Lawn Cemetery in Halifax to lay wreaths on the graves of Titanic victims. When she was denied the right to testify to the Titanic inquiry because she was a woman, Brown wrote her own account of the sinking, which was published by various newspapers. Margaret Brown died in New York in October 1932. |

|

| The violin belonging to Titanic's orchestra leader, 33-year old Wallace Hartley. A gift to Hartley from his fiancee, Maria, on the occasion of their engagement in 1910, Hartley played this violin as Titanic's band sought to calm nervous passengers anxiously waiting their turn to board the lifeboats. Hartley and his fellow musicians, who died in the sinking, were later celebrated as heroes for their stoicism. Their actions inspired the popular phrase, 'And the band played on' to describe bravery in the face of adversity. |

|

| Visitors end their tour of the Titanic Experience with a small gallery showcasing the impact of the Titanic disaster on popular culture. A variety of items are on display, including film posters, toys, models, artwork, and commemorative souvenirs, reflecting the enduring public fascination with this most famous of shipwrecks even after more than 110 years. |

|

| A display on the pocket watch presented to Captain Arthur Rostron of the Cunard liner Carpathia for his vessel's courageous rescue of 713 Titanic survivors amidst the ice-infested waters of the North Atlantic. The pocket watch was awarded to Rostron by the widows of wealthy businessmen John Jacob Astor, George Dunton Widener, and John Thayer at a lunch hosted at the Astor manor in New York on 31 May 1912, precisely one year after Titanic's launch. While their husbands drowned, the wives were rescued from Titanic's lifeboats by Rostron and his crew on the Carpathia on 15 April 1912. Rostron went on to command some of the Cunard Line's most famous steamships, including Mauritania and Lusitania, before retiring in May 1931 and dying in November 1940, aged 71. RMS Carpathia transported troops and supplies between North America and Liverpool and Glasgow during the First World War and was sunk off the southern coast of Ireland by a German submarine on 17 July 1918 while sailing in convoy from Liverpool to Boston, Massachusetts. |

|

| A close-up view of Captain Rostron's 18-carat gold Tiffany & Company pocket watch. The watch bears an engraved message reading, 'Presented to Captain Rostron with heartfelt gratitude and appreciation of three survivors of the Titanic, April 15th 1912, Mrs. John B. Thayer, Mrs John Jacob Astor and Mrs George D. Widener.' The back of the watch is engraved with Captain Rostron's monogram, AHR, in blue. |

|

| A view of Titanic Belfast from the adjacent Olympic Slipway. Now a public plaza, this site once accommodated Nos. 2 & 3 Slips of the bustling Harland & Wolff shipyard and it was here that Olympic and Titanic were constructed, side-by-side. The Olympic class liners were so big that Slips 2 and 3 were specially constructed to accommodate them, with concrete floors made of reinforced concrete 1.4 metres (46 feet) thick. A plaque mounted on one of the former slipway keel blocks on 31 March 2009 commemorates the centenary of Titanic's keel laying. |

|

| To provide visitors a sense of the immense size of the Olympic class liners, the outlines of Olympic and Titanic are depicted on the paving stones. The white lines outline the ships' deckhouses, lifeboats, and hull sides. The tall lampposts are positioned in the exact locations where the columns supporting the massive Arrol Gantry enclosing the slipways once stood; the actual Arrol Gantry stood 69.5 metres (228 feet) tall, more than three times the height of the current lampposts. |

|

| While the former slipways are today a peaceful space which commemorates both the Olympic class liners and the victims of the Titanic disaster, in 1910 it was swarming with shipyard workers, hammering and riveting steel plates as enormous steam-powered cranes hauled parts and equipment overhead. Olympic's keel was laid in Slip No. 2 on 16 December 1908 and 4,000 men were involved in her construction, working 49-hour weeks for about £2 per week and with only 30 minutes off for lunch each day. Olympic was launched on 20 October 1910, with fitting out being completed by the end of May 1911. After serving as a troopship during the First World War, Olympic returned to passenger service until being retired in 1934 and scrapped at Inverkeithing, Scotland in 1935. |

|

| To the south, across the road from Titanic Belfast, is the historic Hamilton Graving Dock. The dock is named after James Hamilton, the Chairman of the Belfast Harbour Commissioners, the organisation responsible for managing, developing, and improving the city's port. The dock was officially opened on 2 October 1867 by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Marquis of Abercorn. |

|

| A set of interpretive panels installed next to the Hamilton Graving Dock tell the story of Belfast's development and the construction and use of the dock. Work on Hamilton Dock and the adjoining Abercorn Basin commenced in February 1864 on a site conveniently located near the Harland & Wolff shipyard. Its excavation coincided with a period of unprecedented economic and population growth in Belfast, which between 1821 and 1901 grew faster than any other British city. Built by a team of 450 workmen using picks, shovels, and hand- and steam-powered dredgers, the dock and basin were completed in 1867 at a cost of £30,000. (In comparison, the cost of building a small house in the 1860s was around £150.) Crafted from concrete and sandstone bound together with water-resistant lime mortar, Hamilton Dock was Belfast's third graving dock and the first built in over 40 years. It was almost twice as large as the preceding dock, completed in 1826. The Belfast Harbour Commissioners leased the dock to the shipyards and, once a ship was safely dry docked with the help of a team of Harbour Commission employees, the shipyard workers would carry out whatever work was required. Ships typically spent a maximum of two weeks in the dock, being cleaned, re-painted, fitted with new equipment, or repaired. As graving dock rental rates were high, on average £13 for a typical stay in the late 1860s, shipowners preferred to use them only when it was absolutely necessary. Although refurbished in 1948 and used until the 1990s, Hamilton Dock deteriorated thereafter until 2009, when restoration work commenced. This included the installation of a new watertight gate to replace the original floating caisson, reconstruction of the dock's pump house, and the relaying of the cobblestones surrounding the dock. |

|

| SS Nomadic sits on keel blocks in the historic Hamilton Graving Dock on Queen's Island, Belfast. Hamilton Dock measures 137 metres (450 feet) in length, 15 metres (50 feet) wide at the bottom, and seven metres (22 feet) deep and was able to comfortably accommodate two ships simultaneously. When it was in use, Hamilton Dock could hold approximately three million gallons (13.64 million litres) of water, equivalent to the volume of 5.5 swimming pools; it could take up to six hours to empty the dock using the steam-powered underground centrifugal pump. Of the same vintage as the Olympic class liners and also built for the long-defunct White Star Line, SS Nomadic is today considered the last remaining White Star Line vessel. |

|

| The Hamilton Dock caisson, built by Harland & Wolff in 1867, is one of the oldest surviving vessels made by the famous shipbuilder. It was designated 'Hull No. 50' on the company's shipping list. The caisson is a hollow gate which was used to close off the entrance to the dock so that it could be pumped free of water to enable work on a ship inside. The caisson is made of wrought iron and is hollow and shaped like a ship's hull. The caisson would be floated into position in the dock entrance and then filled with water so that it would sink into place, sealing the entrance. Once in place, it was possible to cross the dock via the wooden deck atop the caisson. When the dock needed to be re-flooded, a steam-powered pump in the nearby pump house would remove the water from the caisson, causing it to float and the dock to fill with water. |

|

| SS Nomadic was designed by the same team of Harland & Wolff draughtsmen, overseen by naval architect Thomas Andrews, that had designed the Olympic class liners for the White Star Line. Built to tender passengers between the port of Cherbourg, France and the Olympic class liners anchored offshore due to the shallowness of Cherbourg's harbour, Nomadic featured decor that was impressive for a tender. Indeed, Nomadic and her smaller sister, Traffic, were intended to reflect the grandeur of the White Star liners and were given relatively lavish decor for tenders, with benches, tables, and wall panelling selected from the same Harland & Wolff workshops producing these fittings for Olympic and Titanic. In this way, passengers aboard the tenders were given a subtle taste of what to expect when boarding White Star's liners for their transatlantic crossing. |

|

| Nomadic was built by Harland & Wolff at the same time as the shipyard was constructing Olympic and Titanic. Nomadic was launched on 25 April 1911, with fitting being completed two months later. Nomadic's benches, wall panelling, and staircases adopted many of the same patterns used on the Olympic class liners. Her propellers, anchors, and rigging were installed in a dry dock, very likely the same Hamilton Graving Dock in which she is now displayed. |

|

| A stern view of Nomadic, with her two propellers visible. White Star Line took delivery of Nomadic from Harland & Wolff on 27 May 1911 and, under the command of Captain Boitard, sailed for Cherbourg, France, its home port, arriving on 3 June. In Cherbourg, Nomadic was registered to Mr Auguste Lanièce, White Star Line's agent in the city. In addition to Nomadic's French crew of six officers and ten men, White Star Line employed land-based staff in Cherbourg, including coal trimmers and labourers to help move passenger baggage, cargo, and mail sacks on and off the tender. Captain Boitard was still in command of Nomadic when she delivered passengers to Titanic during the liner's stopover in Cherbourg on 10 April 1912. |

|

| After serving as an auxiliary minesweeper and military tender in the First World War, Nomadic returned to commercial tender service and was sold to the Cherbourg Transshipment Company in 1927, remaining contracted to ferry White Star Line passengers. Sold again in 1934, this time to the Cherbourg Towage and Salvage Company, Nomadic was renamed Ingenieur Minard. When Cherbourg was occupied by German forces in June 1940, Ingenieur Minard sailed for Portsmouth, England and served throughout the Second World War as a troopship ferrying trainee soldiers between Southampton and the Isle of Wight. In 1945, Ingenieur Minard returned to Cherbourg and to tender service for transatlantic liners. Following retirement in November 1968, the ship was sold and, reverting to her original name, used as a floating restaurant, conference centre, discotheque, and nightclub on the River Seine in Paris from 1974 to 1996. Moved to Le Havre in April 2003, Nomadic was put up for auction and, on 26 January 2006, purchased by the Northern Ireland Department for Social Development for £171,000. Nomadic was returned to Belfast on 17 July 2006 and extensively restored in 2011-12, becoming a key attraction in the redeveloped former industrial land of Queen's Island. |

|

| The 1,273 gross ton Nomadic measures 71 metres (233 feet 6 inches) long, with a beam of 11.3 metres (37 feet 2 inches). Her two double-expansion engines, powered by two boilers, drove twin propellers, giving Nomadic a top speed of 12 knots (22 km/h). She could carry up to 1,000 passengers and their baggage, as well as cargo and mail sacks. |

|

| The gangway leading onto Nomadic's upper deck First Class passenger saloon. Of the maximum capacity of 1,000 passengers that Nomadic could carry, the segregated passenger decks could accommodate approximately 400 First Class, 500 Second Class, and 100 Third Class travellers. |

|

| Looking aft along the port side of Nomadic's hull in Hamilton Dock. The ship's four decks were laid out in a practical manner, with saloons for First Class and Second Class passengers located on the upper and lower decks forward and aft of the engine room, respectively, and Third Class passengers carried in a section of the lower deck near the stern. |

|

| Scale models of White Star Line's two tenders, SS Nomadic (top) and SS Traffic (bottom), both built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast and completed in May 1911. While Nomadic carried First Class, Second Class, and occasionally some Third Class passengers, Traffic carried only Third Class passengers. Typically Nomadic would carry Third Class passengers only when their numbers were so low that there was no justification for running both tenders. |

|

| A closer look at the model of SS Traffic. Traffic carried up to 1,000 Third Class passengers, their luggage, and mail sacks from the French port of Cherbourg to the Olympic class liners anchored offshore. Measuring 56 metres (184 feet) in length, with a beam of 10.9 metres (36 feet), the 675 gross ton Traffic was powered by a single double-expansion steam engine driving a single propeller. The ship had a top speed of 9 knots (16.5 km/h). Like Nomadic, Traffic was sold to the Cherbourg Towage and Salvage Company in 1934, being renamed Ingenieur Reibell. In September 1939, the French Navy requisitioned Ingenieur Reibell and renamed her X23. With the occupation of Cherbourg by German troops in June 1940, X23 was scuttled but later salvaged by the Germans and used as a coastal patrol vessel. On 17 January 1941, the ship was torpedoed by the Royal Navy, again being salvaged by the Germans but scrapped in light of the severity of the damage. |

|

| The ladies' waiting room for First Class female passengers, laid out for tea. While much of Nomadic's interiors were reproduced during the restoration work, there are still several examples of original moulded wood panelling aboard, including the two oak panels to the left of the large square window. |

|

| One of the staircases between the lower and upper decks on Nomadic, in this case between the First Class sections of both decks. The former passenger saloons on Nomadic's upper and lower decks are now home to various exhibits recounting the ship's construction, service history, crew, and restoration. |

|

| The bar in the First Class saloon on the upper deck allowed First Class passengers to enjoy a free drink during the short journey from Cherbourg to the Olympic class liners anchored offshore. The carved wood bar is an original feature, dating to 1911. In the 1960s, it was moved towards the First Class entrance vestibule, but was relocated to its original location here during Nomadic's restoration in 2012. |

|

| A table for First Class passengers on the upper deck near the bar. The great majority of the panelling above seat level in this area is original, fitted by Harland & Wolff in 1911. All panelling in First Class areas was made of oak. While some panels were removed by collectors, many of these were salvaged and returned to the ship during the 2012 restoration; where original panelling was missing, replicas were made. |

|

| Looking aft from the First Class saloon to the second class saloon at the aft end of the upper deck. When in service, four sets of sliding metal grilles (Bostwick gates) were used to separate First and Second Class passengers on the upper deck. |

|

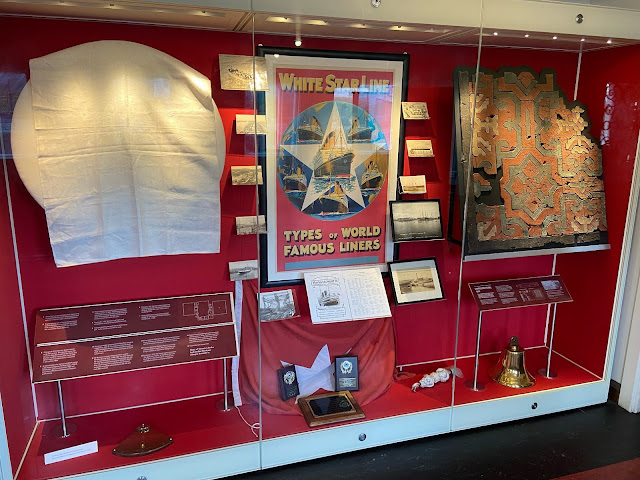

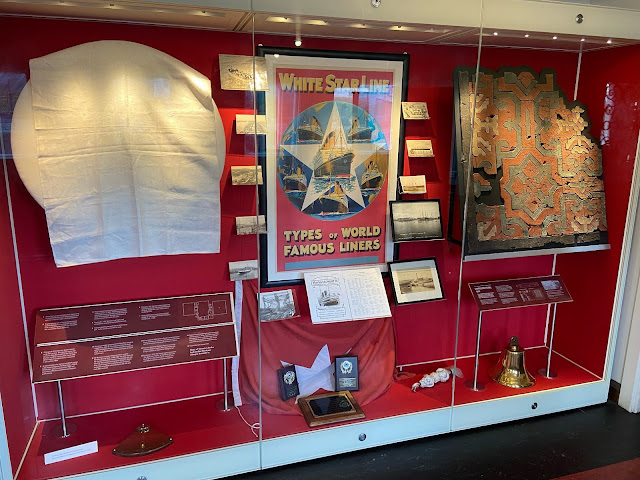

| A cabinet displays various artefacts from the White Star Line, including a damask tablecloth bearing the company logo; an original White Star Line promotional poster, c. 1920; and a large section of Nomadic's original inlaid linoleum floor tiling. Linoleum was produced by heating and cooling linseed oil mixed with small particles of corkwood, resins, and colour pigments; once cooled and solidified, tiles were cut out using a stencil and attached to a hessian backing material to create an interlocking mosaic pattern. These original linoleum tile fragments were discovered outside the men's toilets aboard Nomadic and conserved as part of the ship's 2012 restoration. Additional items in the display include historic photographs of Cherbourg harbour, White Star Line ships, and Queen's Island in Belfast; a shipping timetable; postcards; and a c. 1932-34 advertisement for Harland & Wolff. |

|

| These original mahogany doors on the upper deck lead to one of the the Second Class entrance vestibules. Nomadic's wide entrance vestibules were designed to permit the rapid and efficient embarkation and disembarkation of passengers, reflecting the ship's role as a tender. With thousands of local people waiting to witness RMS Titanic's arrival off Cherbourg, at 5:00 pm on 10 April 1912, Nomadic and Traffic ferried passengers out of the harbour and waited over an hour in choppy seas until Titanic arrived and anchored. After Traffic had finished disembarking her 102 Third Class passengers onto Titanic, Nomadic came alongside the liner to disembark her 172 First and Second Class passengers via gangways laid between her flying bridge deck and Titanic's E Deck. |

|

| An interactive display invites visitors to select an item of luggage as shown on the screen to learn more about what passengers packed for a journey on the Olympic class liners. |

|

| The staircase linking the Second Class saloons on the upper and lower decks. Although there were First and Second Class saloons on both the upper and lower decks, each class used its own segregated staircases. |

|

| Nomadic's Second Class saloons were less decorative than the First Class saloons but still much more luxurious than typical tender vessels of the period. While oak was used for all panelling in First Class, the panelling in Second Class was crafted from mahogany. Although Second Class passengers usually outnumbered First Class passengers, there was 30% less deck area allocated to Second Class passengers than to those in First Class. |

|

| Another view of the lower deck Second Class saloon, with a door leading aft to the space used to accommodate any Third Class passengers. The Second Class saloons, like this one, featured more modest decor and Second Class passengers did not have access to the bar on the upper deck, instead being given only a drinking fountain outside the Second Class gentlemen's lavatories. Most Second Class passengers were former European emigrants who had forged better lives in North America and travelled home to Europe on the liners to visit family and friends. Such journeys back to 'the old country' would have been very different than the initial outward voyages, in which poor, unskilled emigrants travelled in Third Class steerage accommodation, crammed into onboard dormitories, fed poorly, and with little or no access to medical care. |

|

| The aft end of Nomadic's lower deck accommodated Third Class passengers bound for Olympic and Titanic. As the majority of Third Class passengers were carried aboard SS Traffic, a dedicated tender for Third Class passengers, Nomadic only occasionally carried people in this fare class. Unlike the First and Second Class saloons, the Third Class saloon was extremely austere, as Third Class passengers were generally poor migrants crossing the Atlantic for a new life in North America. Despite the luxury afforded to higher class passengers, half of the White Star Line's revenue was generated from Third Class ticket sales. |

|

| A closer view of the sloping sides of the port aft section of the lower deck. Used for Third Class passengers, this space had no decor and was outfitted with simple wooden benches and tables. |

|

| Located in the First Class lower deck saloon is a display on Ingenieur Minard's Second World War service, noting the ship's narrow escape from Cherbourg following the German occupation of France and her role as a troop transport until 1945. Although the Royal Navy intended to scrap the 34-year old vessel after the end of the war, the director of the Cherbourg Towage and Salvage Company, the pre-war owner of Ingenieur Minard, arranged for her transfer back to Cherbourg. |

|

| The First Class saloons on the forward portions of Nomadic's upper and lower decks were the most lavishly decorated spaces on the ship. The decks were laid with intricately-patterned linoleum tiles, as seen here. Nomadic's decorative styles were more conservative than those on Olympic and Titanic. While Nomadic's First Class spaces are similar in style to Olympic's Second Class decks, her Second Class spaces echo Olympic's Third Class decks. |

|

| The forward starboard corner of the lower deck First Class saloon. The backs of the upholstered chairs bear a white star, the symbol of the White Star Line, while the white painted oak wall panelling features plaster moulding with classical decorative motifs, such as floral garlands and urns. Fluted Corinthian-style columns flank the port holes, with similarly-styled ornamental corbels connecting the deckhead beams with the walls. |

|

| The passageway skirting the space formerly occupied by Nomadic's two double-expansion steam engines, which generated 550 horsepower, with each engine driving a propeller. The engines were built by the engine and boiler workshop at the Harland & Wolff shipyard, the same workshop that constructed the enormous steam engines used on Olympic and Titanic. Smoke from Nomadic's boilers was carried in flues spanning the height of the ship, to be vented through the funnel directly above the engine and boiler room. |

|

| A display on Nomadic's Cherbourg-based crew of up to ten crewmen and six officers. Each crewman worked two of the six watches per day, with each watch lasting four hours. A minimum of one crewman was aboard Nomadic at all times to keep the boiler fires burning and to provide security. Since it would take 36 hours from a cold state to generate sufficient steam pressure to power the ship's engines, the boilers were always kept running, even on days the ship was not in use. |

|

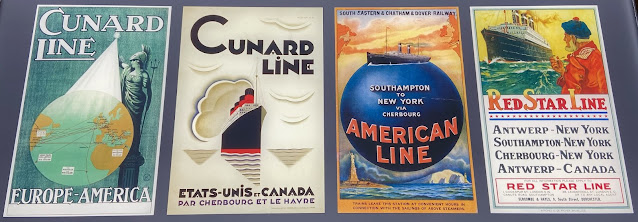

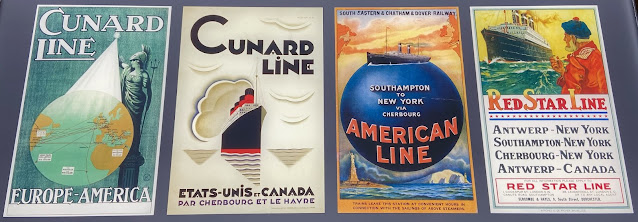

| A display of of early-20th century posters from competing steamship lines. As competition for passenger traffic was fierce among the shipping lines, eye-catching posters like these were used to attract customers. Although Cherbourg was primarily a military port until 1895, it became an important stopover for transatlantic liners in the early 20th century after a quayside train station allowed passengers from across Continental Europe to travel direct from Paris. By 1913, seven steamship companies were regularly stopping in Cherbourg while en route to or from tplaces like Southampton, England and Hamburg, Germany. |

|

| Nomadic's crew was accommodated in this small compartment near the forward end of the lower deck. As a tender, Nomadic did not venture far from shore, so the hammocks and bunks in the crew space may only have been used by the ship's night watch. |

|

| Access to the crew space was originally through a hatch from the forecastle, above, with another hatch on the floor leading to the engineering deck. The crewmen cleaned every part of the ship on a daily basis, including their own quarters. The only time the crew were permitted in the passenger spaces was to scrub the decks, polish the brass, and dust the mouldings. |

|

| The lamp room was used to store oils and other flammable substances required on Nomadic. The ship's two anchor chains were stored in a space below the lamp room, accessed via a hatch marked 'CL' (for Chain Locker). To lower the anchors, the steam-powered windlass on the forecastle pulled the chains up through pipes in the crew compartment and let them run out through pipes in the lamp room leading to the hawse (a hole) in the ship's hull plating. |

|

| Various lanterns and the supplies of oil to feed them were stored in the lamp room at the forwardmost end of the lower deck. |

|

| Nomadic was moved to Hamilton Dock permanently in 2009. Given that the ship had been vandalised, looted, and had her interiors stripped by collectors over the years in France, as well as the discovery of concealed leaks and wet rot in the dilapidated hull, an extensive restoration program was required. The ship's original 1911 plans were used by Harland & Wolff to reconstruct her dismantled flying bridge deck and bridge deck and a new funnel was constructed, the original having been removed in the early 1970s as part of her conversion into a floating restaurant. Wood and plaster interior mouldings were carefully restored or, where missing, were precisely reproduced. Today, SS Nomadic serves as a fascinating glimpse into Edwardian era shipbuilding and the age of the transatlantic liners. |