Spanning five years, eight months, and five days, the Battle of the Atlantic was the longest military campaign of the Second World War, lasting from the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 until the German surrender on 8 May 1945. So vital was this campaign to Britain's war effort and home front morale that wartime British Prime Minister Winston Churchill claimed that the '[t]he only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.' While the Battle of the Atlantic was an Allied effort spanning the ocean between Europe and North America and principally involving the naval and air forces of the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, command of the battle in the eastern Atlantic was exercised by the Royal Navy's Commander, Western Approaches. Established in 1939 and originally based in the southwestern port of Plymouth, the Western Approaches Combined Headquarters moved to Derby House in Liverpool in February 1941 following the decision to re-route Allied transatlantic convoys around the north of Ireland in response to the threat posed by German U-boats and aircraft. From then until its closure on 15 August 1945, Western Approaches Command was responsible for ensuring the safety of inbound and outbound Allied merchant shipping in the waters around the UK and prosecuting the war against German U-boats, surface vessels, and aircraft through its operational command of convoy escort groups and naval and air assets. Escort and anti-submarine forces allocated to Western Approaches Command were based in Liverpool, Greenock, Londonderry, and Belfast. Although three Royal Navy admirals held the title of Commander, Western Approaches, the most famous of them was the longest-serving, Admiral Sir Max Horton, who held command from 19 November 1942 until the end of the war.

With the Germans and Japanese defeated, Western Approaches Command was disbanded and the Combined Headquarters was largely stripped of equipment and sealed up. While the rest of Derby House was later converted into modern offices, renovation of the reinforced concrete bunker in the building's basement was deemed impractical. After decades of neglect and deterioration, the bunker was restored to its wartime appearance and, in 1993, opened to the public as the Western Approaches Museum. In 2017, the museum was taken over by Big Heritage, a social enterprise group, which has invested in significant restoration work, including the opening of several parts of the Combined Headquarters bunker sealed since the 1960s.

Below: The front and reverse sides of the admission ticket at the Western Approaches Museum. The ticket is a reproduction of the wartime day pass issued to visitors to secure government and military installations, outlining the conditions of entry. The four circles on the reverse side of the ticket are for stamps that today's visitors can add at designated stations throughout the museum.

With the Germans and Japanese defeated, Western Approaches Command was disbanded and the Combined Headquarters was largely stripped of equipment and sealed up. While the rest of Derby House was later converted into modern offices, renovation of the reinforced concrete bunker in the building's basement was deemed impractical. After decades of neglect and deterioration, the bunker was restored to its wartime appearance and, in 1993, opened to the public as the Western Approaches Museum. In 2017, the museum was taken over by Big Heritage, a social enterprise group, which has invested in significant restoration work, including the opening of several parts of the Combined Headquarters bunker sealed since the 1960s.

Photos taken 31 October 2024

|

| The Western Approaches Museum is located in Derby House, at the corner of Rumford Street and Chapel Street. |

|

| The entrance to the Western Approaches Museum. |

|

| The first stop on the self-guided tour route is a small theatre playing a looped introductory film about the role and work of Western Approaches Command during the Second World War. |

|

| The fictional Parker's confectionery shop features strips of tape over the glass in the window and door, a measure adopted by business and home owners against the effects of blast from German bombs. |

|

| The interior of Parker's confectionery shop, with boxes and glass jars of rationed sweets, as well as newspapers and magazines. |

|

| A wartime propaganda poster produced by the Ministry of Food, encouraging Britons to make potato soup and to feed vitamin A-rich carrots to children. |

|

| The other side of the Dock Lane recreation contains an ice cream shop whose owners have closed their business during the war and, next door, a boarded-up bomb-damaged building. |

|

| A narrow corridor leads from the Teleprinter Room to the Switchboard Room and Code Room on the right and the Operations Room on the left. |

|

| The Second World War uniform of a Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force. An officer at the rank of Wing Commander served as the RAF Duty Commander in the Operations Room. |

|

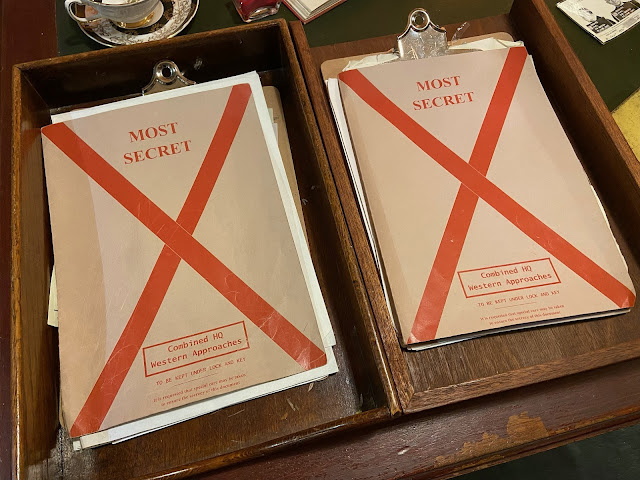

| Desk trays in the Operations Room hold documents classified 'Most Secret', containing intelligence on German submarine and aircraft movements derived from decrypted radio signals or other sources. |

|

| The layout of the Operations Room has been preserved as it was when the Western Approaches Combined Headquarters bunker was shuttered at the end of the war in August 1945. |

|

| Ascending from the Basement Level to the Lower Ground Floor Level, visitors arrive at the entrance to the suite of rooms used by the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches and his Flag Lieutenant. |

|

| This small bedroom, with a window overlooking the Operations Room below, was where the Commander-in-Chief could rest during long periods on duty in the bunker. |

|

| A spartan corridor leads onward from the Commander-in-Chief's suite. |

|

| A motorcycle used by Wren dispatch riders to deliver important messages between military and naval facilities in the UK during the Second World War. |

|

| An original sign and indicator from the GPO Switch Room. |

|

| Visitors pass an original building sign on their way out of the Western Approaches Museum. |